Bathing to Beat the Heat in Early Charleston, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

Before the advent of air conditioning and running water in the Charleston area, Lowcountry residents of all descriptions pursued a number of indoor and outdoor strategies to gain relief from the sultry summer heat. Bathing was a luxury enjoyed by a minority of the population, and a practice avoided by some. Their world was far dirtier and smellier than the squeaky clean place we now inhabit. In today’s program, we’ll peek behind closed doors to explore the rise of indoor bathing within both private residences and commercial bath houses.

The story of bathing in early Charleston is sufficiently complex that one could easily write a dissertation or fill a small book on the subject. My goal is to provide an overview of the most salient points and suggest an outline for anyone wishing to plumb the depths of this watery topic. As the heat and humidity envelop our community every summer, we’re inclined to wonder out loud how earlier generations could stand this subtropical climate without the modern convenience of air conditioning and a daily shower or two. Extant historical resources contain sparse evidence of bathing in colonial-era South Carolina and the early years of the new United States of America, however, and this archival silence raises a legitimate question: Did our forebears consciously avoid the pleasures of a cool bath or a plunge in the ocean on a hot summer’s day?

In the past as in the present, one’s relationship with water reflects one’s cultural background. Most of the documentary evidence of bathing in Charleston’s past pertains to White people of European descent who inherited attitudes and practices influenced by centuries of Christian thought. Our community included a smaller number of people espousing Jewish and Islamic beliefs that included different cultural associations with water and bathing. In the eighteenth century, for example, most Americans of European descent never learned to swim—even mariners accustomed to a seafaring life—while most of the Africans brought to this country in chains learned to swim and to dive at an early age.[1] They were likely drawn to Lowcountry bodies of water when circumstances allowed, but few stories of their aquatic opinions now survive.

In the eighteenth century, most adults in Britain and their American counterparts regarded bathing as a medical remedy rather than a desirable recreational pursuit. Dr. Lionel Chalmers of Charleston, for example, recommended a “cold bath” as a treatment for gout and other conditions in a treatise published in 1776: “The cold bath also should be used daily throughout the summer, by plunging headlong into salt water. . . . If the sea be not near, so much common salt should be dissolved in fresh water, as will bring it to an equal degree of saltness [sic] and weight with that of the sea; and then two or more pailfuls of this should be poured over his head as he sits in a large vessel.”[2] Some Charlestonians were definitely following the doctor’s orders in the years before the American Revolution because advertisements for “oil case caps for bathing,” imported from England, appeared in local newspapers as early as 1772.[3]

After the War of Independence, Dr. David Ramsay of Charleston published a more rational prescription for bathing in 1790: “Cold bathing, under proper regulations, is an excellent preventive of the diseases of this country. As heat relaxes, it is obvious that cold must brace. Once in twenty-four hours, to immerse the body in cold water, most powerfully strengthens the whole system. . . . By bracing the whole system, it destroys that predisposition to diseases, which is brought on by the relaxing qualities of heat and moisture. It is farther serviceable by keeping the skin constantly clean. Such is the excessive perspiration in this country, in the summer, that frequent washings are indispensably necessary to preserve cleanliness. . . . So many diseases might be prevented, and so much good might be done by a judicious use of bathing, that every gentleman ought to have an apparatus in his house for that purpose. Sometimes cold water, and sometimes tepid, ought to be used. In other cases washing would be preferable to bathing. To adjust these, and several other particulars, and to prevent the mischiefs that might arise from indiscreet bathing, the advice of a physician is often necessary.”[4]

Attitudes towards bathing in Charleston and elsewhere began to change during the 1790s, following the arrival of refugees from the revolutions in France and Saint-Domingue (Haiti). According to witnesses living here at the end of the eighteenth century, the French immigrants were more concerned with routine bathing and personal hygiene in general than their American contemporaries. The “perfect health” of these French émigrées , “in every season of the year,” said a Charleston bathing enthusiast in 1797, was caused “chiefly by the great use they make of the cold bath, and their constant use of wine in a moderate degree, in place of diluted spiritous liquors commonly called grog.”[5] Their local influence, combined with evolving scientific attitudes across the nation, sparked a rise in bathing in the Charleston area during the early years of the nineteenth century.

The story of bathing to beat the heat in early Charleston is not a straight-forward narrative that progresses in a tidy chronological fashion. Rather, it’s more like an album of several parallel stories that share a common theme but feature different characters and settings. Some of the events took place outdoors, for example, while others unfolded behind closed doors. Some involved the use of public resources, while others were purely private ventures. Finally, some of the bathing activities in question involved fresh water, or brackish water, while others took place in the ocean surf. To gain a bird’s-eye-view of this sprawling topic, let’s consider each of these permutations in succession, beginning with indoor topics.

Indoor Private Bathing Facilities:

Most Charleston homes built before the twentieth century did not include plumbing or an interior space dedicated for water purposes. The act of bathing in the distant past, therefore, required a lot of labor and resources. First, one needed a nearby source of fresh water—either a well or a cistern. Well water had to be drawn and then carried in buckets to an indoor receptacle like a tub or basin. If one had a cistern to collect rainwater under or adjacent to the house, one could install pipes and pump the water from the cistern into an interior room used for bathing. Some large houses had cisterns in the attic space that allowed residents to funnel the rainwater down pipes directly to a bathing receptacle. If one preferred a warm bath, one needed to procur firewood or coal and have access to a hearth or stove and utensils in which to heat the water.

The idea of soaking one’s entire body in a tub of warm water was a most extravagant luxury in centuries past. Someone had to draw the water from the well or cistern, heat the water in a pot over a fire or stove, and deliver numerous pots of hot water into the tub. This work became easier in the early nineteenth century following the proliferation of mass-produced boilers and pipes associated with new-fangled steam engines. Most households in antebellum Charleston could not afford a residential water boiler, however, so warm baths remained a luxury until the early twentieth century. One could either pay to visit a commercial bath house on occasion, or take a sponge bath at home with a much smaller volume of warm water, or simply avoid bathing during the coolest months of the year.

“Bathing frequently in winter is requisite to comfort,” said a Charleston newspaper in 1839, “and in summer it is absolutely indispensable. No family ought to be without its bathing tub.”[6] The item in question might be a crude wooden structure like a trough or a barrel, or an elegant basin made of wooden slats assembled by an expert cooper. One could also take a standing bath in a relatively small tub made of tin or copper, or a lounging, recumbent bath in a longer tub made of double-walled tin. Cast-iron tubs with smooth enamel finishes were not generally available until the early 1900s.

The term “water closet” came into use in the last quarter of the eighteenth century in England and in the United States, with two different connotations. Early patent flush toilets were frequently called water closets, but that term was also applied to the small rooms enclosing them.[7] In the latter architectural sense, a water closet of the early nineteenth century might also include pipes bringing cool water from a cistern to a bathing tub fitted with a drain to carry the waste water out of the house. Modifying older homes for such purposes wasn’t easy, but it was a growing trend. The aforementioned news item from 1839 opined that “every house designed as a human dwelling [henceforth] should have a bathing room. This need not to be a large and expensive apartment, such as would in any considerable degree increase the expense of the building—it may merely be a closet—five by seven feet would be ample, and if opening directly from a convenient bed room, a still less size will answer the purpose. But at any rate let it be a bath, if it be set in one corner of a bed room or a shed. No dwelling house can be regarded as properly furnished without one.”

In antebellum Charleston, numerous homeowners either created a bathing space within an outbuilding—like a shed or a detached kitchen structure—or pursued one of several strategies to adapt their main house for bathing. Stephen Shrewsbury (died 1815), for example, installed a “bathing room” in the above-ground cellar beneath his large, three-story brick residence at the northwest corner of East Bay and Laurens Streets. At the rear of his house, connecting to the detached kitchen, Shrewsbury also framed a wooden extension or “hyphen” containing “another bathing room, with all the necessary fixtures for the shower bath, and a dressing room.”[8] Many older houses in Charleston were fitted with water-plumbed hyphens in the nineteenth century, while the owners of smaller residences often enclosed part of their exterior piazza to cloak the addition of a water closet. Evidence of this sort of modification can still be seen across the city in houses featuring relatively useless, vestigial stubs of once-airy piazzas.

In private residences in urban Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry, the number of bath tubs and bathing rooms steadily increased over the course of the nineteenth century. The paucity of detailed property records renders it difficult to formulate a numerical estimate, but scores of sale advertisements and notices published in local newspapers before the Civil War document the presence of bathing rooms and bathing equipment in residences both urban and rural. In short, the practice of indoor bathing proliferated long before the advent of running water here around the turn of the twentieth century. This point is driven home by a milestone reached in 1854. That summer, Charleston’s City Council appropriated money for the purchase of “bathing tubs for [the] male and female departments” of the notorious Work House on Magazine Street, where slaveowners paid city employees to incarcerate and punish enslaved servants accused of misbehavior. Even the most miserable and maltreated people in the community deserved to wash themselves on occasion.[9]

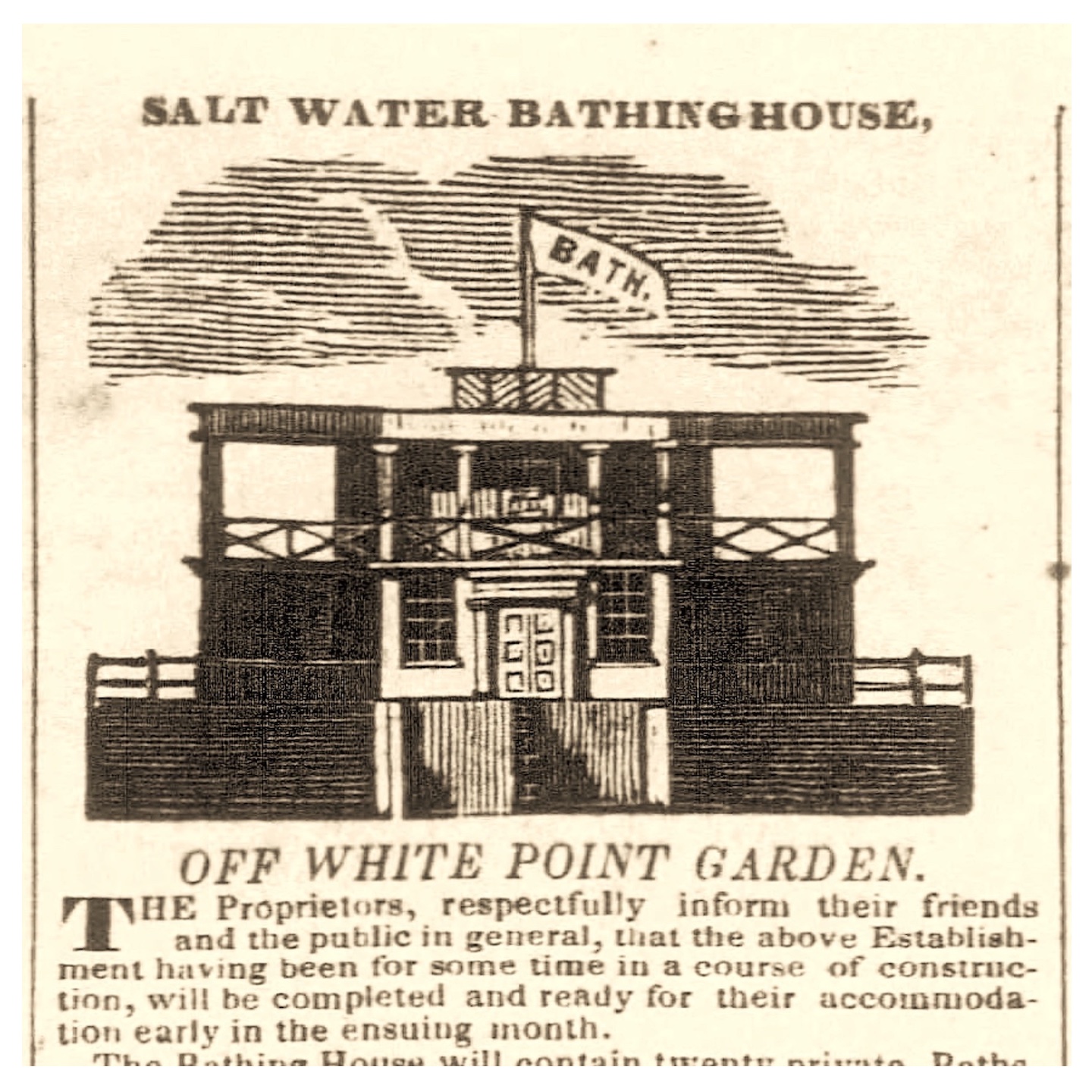

Indoor Commercial Bath Houses:

Charleston, like many urban communities across America and in other parts of the world, eventually acquired its own indoor bath houses where residents without their own bathing facilities or visitors could pay for the privilege of a single bath or purchase tickets for larger number of visits at a reduced rate. This branch of commerce was inaugurated locally by French immigrants who arrived in the 1790s and who continued to dominate the indoor bathing and perfume trade for several generations. Note, however, that none of these local facilities included a communal bath or pool. Charleston’s commercial bath houses were residential structures converted into discrete bathing rooms with individual tubs, in which the proprietors claimed to enforce strict privacy and propriety.

The city’s first French bath opened on Bastille Day (July 14th) 1794 in a house on the south side of Broad Street, near King Street (now No. 93 Broad), where customers could bathe, purchase refreshments, listen to music, and relax with like-minded citoyens.[10] After the first proprietor, Monsieur Bulit, died in a fireworks accident, his widow continued the business at a different location at the northeast corner of Broad and Legare Streets, now occupied by the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist. Here, within a brick structure formerly associated with a lost Horry family mansion, Madame Bulit and then a series of other French proprietors offered warm and cold baths every year from mid-spring to mid-autumn. In 1799 the facility became part of a larger commercial venture called Vauxhall Garden, where customers promenaded through a large garden listening to concerts while sipping a beverage or eating ice cream through the summer of 1820.[11]

Meanwhile, other French immigrants erected a large wooden theater on the west side of Church Street in 1794 and later augmented the premises with outbuildings designed for mixed commercial and residential use. Adjacent to the City Theatre, as it was called in 1803, French proprietors opened a suite of warm and cold baths in a brick structure located between the modern buildings known as 95 and 97 Church Street. The business continued, under a series of proprietors, until the building was consumed by fire in December 1863. Similarly, a series of French proprietors operated a modest bath house on the south side of Queen Street, opposite Philadelphia Alley, from 1810 until at least 1829.[12] Members of the Rame family (Louis, then Claude) operated a popular confectionary store from the early 1820s to 1846 on the west side of Meeting Street, opposite Pinckney Street. After a fire destroyed that block in 1835, Claude Rame immediately rebuilt and transformed the business into a multi-purpose social hall offering confectionaries, ice cream, and bathing rooms for both ladies and gentlemen year round.[13]

The rise of indoor plumbing in Charleston during the first half of the nineteenth century was also contemporary with the rise of the modern concept of a tourist hotel. While taverns of the eighteenth century generally provided minimal creature comforts for overnight guests, hotels in antebellum America offered a greater range of amenities that often included wash rooms. The famous Planters’ Hotel on Church Street, for example, did not include bathing amenities when it opened in 1809, but added the desired facilities during a major renovation in the early 1850s (now part of the Dock Street Theatre complex). Similarly, the massive Charleston Hotel on the east side of Meeting Street, between Hayne and Pinckney Streets, opened in 1839 without bathing facilities and scrambled to add them in 1854.[14] By that time, discerning travelers expected to find bathtubs in their hotels—either in shared or private bathing rooms, depending on the grandeur of the edifice in question.

The published advertisements for Charleston’s early commercial bathing establishments tell us little about their interior arrangements, the nature of the equipment, or the experience in general. Considering the pervasive character of slavery within the city, however, we can imagine that enslaved servants—perhaps just women—likely worked at each of these businesses. Someone had to wash the tubs, towels, and rooms, fetch water and accessories, and carry refreshments to customers. When Claude Rame’s confectionary and bathing establishment on Meeting Street was liquidated in early 1846, for example, a sale notice identified “a negro man [named] Camel, 22 years old, confectioner and cake baker, a negro man Henry, 30 years old, confectioner and cake baker,” and “a negro woman Martha, 18 years old, with her child 2 years old, cook and washer.”[15] They toiled year round for no wages, but perhaps they too enjoyed a cool bath at the end of their long summer days in Charleston.

Our survey of bathing history turns next to outdoor venues, including both ocean surf and Lowcountry rivers. Lots and lots of details relating to this exciting and occasionally scandalous topic survive in local newspapers, but I’ve already tried your patience enough for one day. We’ll pause here and resume the conversation next week. In the meantime, I hope this program helps you appreciate the luxurious nature of the daily bath or shower that we now take for granted. Many hundreds of thousands of people inhabited this community in the generations before indoor plumbing, and most of those people toiled under the sun and slept in their clothes. By taking a moment to consider the physical and mental effects of such a lifestyle, we improve our understanding of Charleston’s deep and dirty past.

[1] Kevin Dawson, “Enslaved Swimmers and Divers in the Atlantic World,” The Journal of American History 92 (March 2006): 1327–55.

[2] Lionel Chalmers, An Account of the Weather and Diseases of South Carolina, two volumes (London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1776), volume 2, page 188.

[3] South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 26 May 1772, page 2, “Daniel Hall and Stephen Smith.”

[4] David Ramsay, A Dissertation on the Means of Preserving Health, in Charleston, and the Adjacent Low Country. Read before the Medical Society of South Carolina, on the 29th of May, 1790 (Charleston, S.C.: Markland & M’Iver, 1790), 20–21.

[5] [Charleston] City Gazette, 20 November 1795, page 2, “From the French and American Gazette, published at New York”; City Gazette, 13 July 1797, page 2, “For the City Gazette.”

[6] Charleston Courier, 19 July 1839, page 2, “Bathing,” quoting and endorsing text copied from an undated issue of The Boston Traveler.

[7] See, for example, the advertisement of John Blanch, in City Gazette, 26 May 1797, page 2. Blanch probably made some version of Alexander Cumming’s patent flush toilet with an S-bend in the trap.

[8] City Gazette, 1 June 1815, page 3, sale advertisement “By J. Simmons Bee.”

[9] City Council Proceedings of 23 May 1854, in Courier, 27 May 1854, page 2.

[10] South Carolina State Gazette, 14 July 1794, page 1, “Public Bath”; City Gazette, 9 April 1795, page 3, “The Citizen Cornet”

[11] South Carolina State Gazette, 14 July 1794, page 1, “Public Baths”; City Gazette, 25 May 1797, page 3, “The Widow Bulet [sic].” I plan to explore the history of Charleston’s Vauxhall Garden in a future podcast.

[12] City Gazette, 2 April 1810, page 3, “Publick [sic] Baths”; Courier, 25 April 1825, page 3, “Warm and Cold Baths”; Courier, 25 Mat 1827, page 3, “Bathing Establishment”; Courier, 27 April 1829, page 3, “Charleston Baths.”

[13] Confectioner Louis (or Lewis) Rame was in business at this Meeting Street location by 1823; Claude Rame announced his re-built business in Courier, 15 June 1836, page 3, “Warm and Cold Baths,” and advertised his “bathing establishment” periodically over the ensuing decade.

[14] Courier, 5 January 1854, page 1, “(For the Courier.) The Charleston Hotel.”

[15] Courier, 17 January 1846, page 3, “For Sale or to Rent, the building in Meeting street, at present occupied by Mr. C. Rame.”

NEXT: Bathing to Beat the Heat in Early Charleston, Part 2

PREVIOUSLY: Anson's Landing to Gadsden’s Wharf: A Brief History

See more from Charleston Time Machine