A 'Banjer' on the Bay of Charleston in 1766

Processing Request

Processing Request

Just after sunset in early December 1766, a man walked through a group of people gathered near the waterfront of urban Charleston. The crowd was listening to a “banjer” playing, and an African woman with a memorable face squeezed past the man as he traversed the scene. Later, he discovered that his pockets had been picked, and offered a reward for his lost property. A close reading of his description of this incident identifies several clues that illuminate its context and help us reimagine a forgotten aspect of South Carolina’s musical heritage.

The source of this story is a brief advertisement that appeared in the South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, one of Charleston’s three weekly newspapers of that era. This Gazette was published by Robert Wells and printed within his large book store on the west side of East Bay Street, just north of Tradd Street.[1] The text in question, published on December 12th, 1766, offered a reward for the return of a “pocket-book” or wallet that was allegedly picked from a gentleman’s pocket ten days earlier. The advertisement did not include the name of the gentleman in question; rather, it asked readers to report relevant information to the printer, Mr. Wells. This sort of anonymous request, called a blind advertisement, was very common in newspapers of the eighteenth century. If the printer or one of his employees received any information related to the incident, he would then convey it to the person who paid for the publication of the advertisement. Let’s review the full text of the 1766 advertisement (with its original spelling):

“Picked out of a gentleman’s pocket, about eight o’clock in the evening of Tuesday December 2d, a POCKET-BOOK lined with red silk, containing about two hundred and fifty-five pounds, currency, in different bills, particularly a fifty pound bill, together with several orders, notes, accounts, and other papers, viz. a letter directed to James Hayles, of Cainhoy, and a bill of sale of a grey gelding, signed [by] Benjamin Wofford. The theft is strongly suspected to be effected by a negro wench, who rubbed herself very close to the sufferer as he passed through a croud of negroes assembled at the lower end of Elliott-street, with a banjer playing. The wench is very remarkable, having three or four strokes the mark of her country, upon each cheek, with long divided teeth. Whoever discovers her or any person concerned, shall upon conviction, receive TWENTY POUNDS currency, by applying to the printer hereof, and if any person concerned will discover the accomplices, such person shall be paid TEN POUNDS like money upon conviction of the offenders.”[2]

On its own, this 1766 newspaper advertisement provides an intriguing snapshot of a larger story that will remain forever fragmentary and incomplete. By situating this small story within the larger historical context of Charleston and colonial-era South Carolina, however, we can identify latent clues that improve our understanding of the events in question. The newspaper text contains a number of keywords that we might think of as historical handles. Grasping those keyword-handles with our historically-informed imagination, we can unfold their implicit meanings to see a bigger picture. To begin this process, we might approach the topic with the “Five Ws” of traditional investigation (who, what, when, where, and why). For the purposes of this program, I’ve decided to break this story into five components: action, location, time, and two “actors.”

Action: “A banjer playing.”

The instrument mentioned in this 1766 incident was a cousin of the modern banjo; that is, a portable plucked stringed instrument frequently used to accompany singing and dancing. A typical banjo has a relatively small, disc-shaped body that is covered with a taut membrane like the head of a drum. Modern banjos have a rigid body covered with a synthetic drum head, but early banjos were commonly made of a dried calabash gourd covered with a swatch of sheep or goat skin. Early banjos in America had three or four strings made of twisted animal gut that produced a softer and mellower sound than modern banjos with five steel strings. Regardless of the number, one of the strings is always shorter than the others. This feature creates a characteristic sound that differentiates the banjo from other plucked string instruments.

The instrument mentioned in this 1766 incident was a cousin of the modern banjo; that is, a portable plucked stringed instrument frequently used to accompany singing and dancing. A typical banjo has a relatively small, disc-shaped body that is covered with a taut membrane like the head of a drum. Modern banjos have a rigid body covered with a synthetic drum head, but early banjos were commonly made of a dried calabash gourd covered with a swatch of sheep or goat skin. Early banjos in America had three or four strings made of twisted animal gut that produced a softer and mellower sound than modern banjos with five steel strings. Regardless of the number, one of the strings is always shorter than the others. This feature creates a characteristic sound that differentiates the banjo from other plucked string instruments.

The modern banjo represents a synthesis of several African predecessors. Historians point to various stringed instruments constructed of readily-available materials like gourds, animal skins, and wood that are still used in various West African cultures.[3] Enslaved African captives in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries might not have carried banjo-like instruments aboard the crowded ships that transported them across the Atlantic Ocean, but many of them carried the knowledge required to recreate parts of their musical culture in the New World. By the third quarter of the seventeenth century, Europeans residing among various Caribbean islands reported hearing enslaved Africans playing banjo-like instruments. Spanish, French, Dutch, and English writers in centuries past described these instruments using a variety of names, including bangelo, banshaw, bangil, banjar, banza, and the like.[4] German physician Johann David Schoepf probably heard such an instrument when he visited South Carolina in the early months of 1784. A few weeks after departing from Charleston, Dr. Schoepf described a gourd “banjah” while aboard a ship carrying enslaved people in the Bahamas:

“Another musical instrument of the true negro is the Banjah. Over a hollow calabash (Cucurb lagenaria L.) is stretched a sheep-skin, the instrument lengthened with a neck, strung with 4 strings, and made accordant [i.e., the strings tuned to different pitches]. It gives out a rude sound; usually there is some one besides [the banjah player] to give an accompaniment with the drum, or an iron pan, or empty cask, whatever may be at hand. In America and on the islands they make use of this instrument greatly for the dance. Their melodies are almost always the same, with little variation. The dancers, the musicians, and often even the spectators, sing alternately.”[5]

A well-known watercolor sketch executed in South Carolina around the year 1790 depicts a man playing a banjo-like instrument. Recent scholarship has identified this painting, commonly called “The Old Plantation,” as the work of John Rose, a Lowcountry resident who owned a plantation within modern Beaufort County.[6] Because of that plantation’s proximity to urban Charleston, and because of the regular maritime traffic between rural plantations and the colony’s principal port, it is possible that the “banjer” heard in the city in December 1766 was similar to that depicted in Rose’s painting some two decades later.[7]

Rose’s painting shows a second musician seated next to the banjo player, using a pair of sticks to beat a small drum, and the two musicians accompany several dancers. While the “banjer” playing in urban Charleston might have inspired some listeners to dance in the street, their performance probably did not include a proper drum. The recreational use of drums among the enslaved population, though technically illegal in South Carolina after 1740, was tolerated in the countryside but actively suppressed within the urban limits of Charleston. On the other hand, a man rhythmically slapping a barrel-head, or rattling pairs of rib-bones between his fingers, would not have been in violation of the law.[8]

Most people think of the early banjo in the New World as a rural instrument; that is, something that was built and played by people of African descent who were confined to labor on rural plantations. Surviving descriptions of banjo-like instruments in the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries refer almost exclusively to rural settings. In contrast, the 1766 reference to a “banjer” on the Bay of Charleston places the instrument in an urban setting, and might represent the earliest description of an urban banjo in the United States.[9]

This incident points to the centrality of Charleston within the agricultural economy of early South Carolina. Export crops such as rice, indigo, and later cotton flowed from Lowcountry plantations to the port town under the management of enslaved patroons or boatmen. We can imagine that these patroons might have carried “banjers” (and perhaps other instruments) on these slow riverine journeys to pass the time. After docking at the crowded capital and unloading his owner’s cargo, a banjer-strumming boatman might have found a spot near the wharves to serenade his neighbors and perhaps kick up the dust.[10]

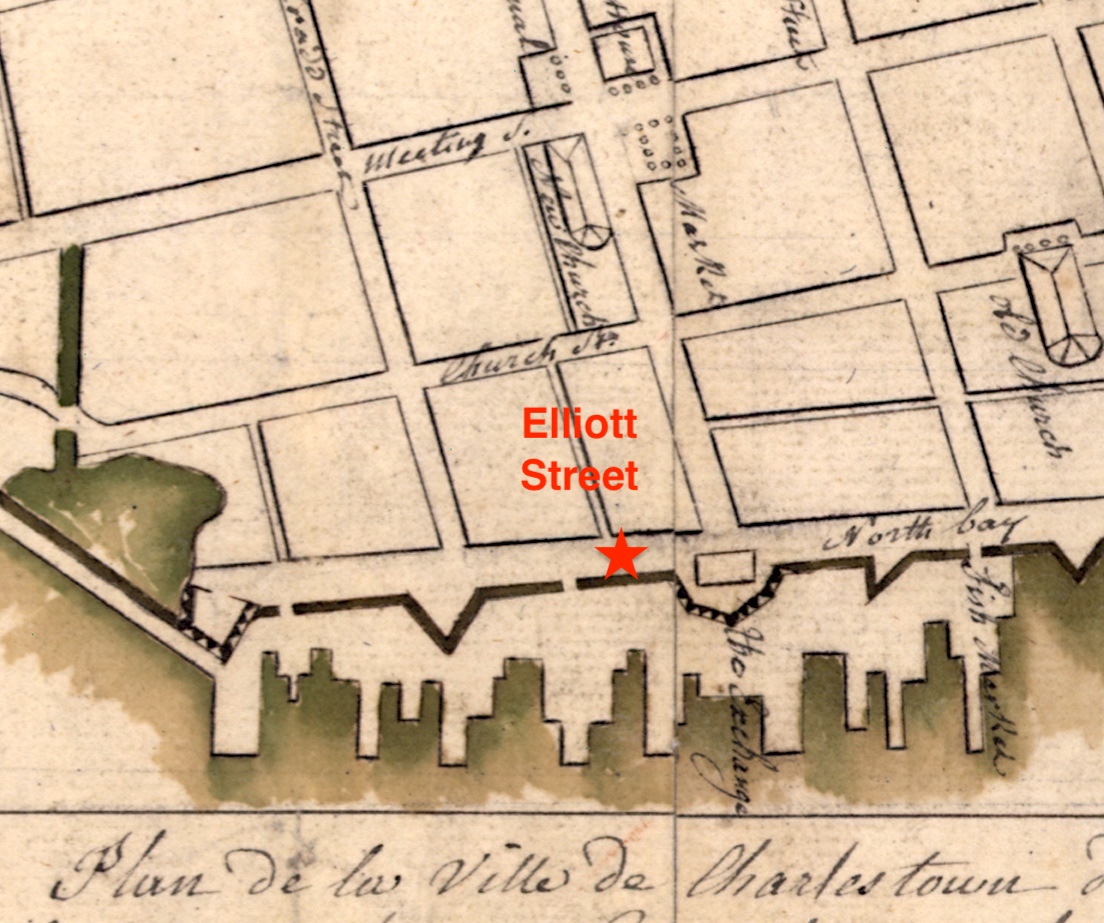

Location: “Lower end of Elliott Street.”

In the eighteenth century, Elliott Street was a narrow, unpaved thoroughfare bounded by a mix of commercial and residential buildings. The “lower” or east end of the street terminated at its junction with “the Bay” (now East Bay Street). Bay Street, fronting the Cooper River waterfront, was the commercial heart of early Charleston because it connected the town to the broader world of maritime traffic. The west side of the street was lined with shops, warehouses, and taverns, all of which housed residential apartments above. The east side of Bay Street, adjacent to the river, was defined by a chest-high brick wall that ran a half-mile in length along a north-south axis. From its creation in the 1690s to its demolition in the mid-1780s, this defensive “wharf wall” or “curtain line” separated Bay Street from the wooden wharves projecting eastward into the Cooper River. The curtain wall was not a continuous line, however; the structure included several authorized gaps or openings to facilitate the movement of people and goods between the street and the wharves.

In the eighteenth century, Elliott Street was a narrow, unpaved thoroughfare bounded by a mix of commercial and residential buildings. The “lower” or east end of the street terminated at its junction with “the Bay” (now East Bay Street). Bay Street, fronting the Cooper River waterfront, was the commercial heart of early Charleston because it connected the town to the broader world of maritime traffic. The west side of the street was lined with shops, warehouses, and taverns, all of which housed residential apartments above. The east side of Bay Street, adjacent to the river, was defined by a chest-high brick wall that ran a half-mile in length along a north-south axis. From its creation in the 1690s to its demolition in the mid-1780s, this defensive “wharf wall” or “curtain line” separated Bay Street from the wooden wharves projecting eastward into the Cooper River. The curtain wall was not a continuous line, however; the structure included several authorized gaps or openings to facilitate the movement of people and goods between the street and the wharves.

Imagine for a moment that you’re standing at the east end of Elliott Street in 1766 and facing eastward, towards the Cooper River. Directly in front of you is the brick curtain wall along the east side of East Bay Street, with ships at anchor beyond the wall. Looking approximately one hundred feet to your right (to the southeast), you see a gap in the wall at the approximate location of the modern street called Boyce’s Wharf. Looking approximately one hundred feet to your left (to the northeast), you see a two-and-a-half-story brick building called the Watch House and Council Chamber (now the site of the Old Exchange Building, built 1768–1771). Between these two landmarks you see an unremarkable stretch of sandy, unpaved street. There is nothing tangible to recommend it as the logical site for any sort of cultural activity. Why, therefore, would a banjo player choose this site for a nocturnal performance in 1766?

The answer to this question is buried in the obscure legal history of early South Carolina. The site of the “banjer” performance on December 2nd, 1766, was the legally-defined gathering spot for porters—day-laborers—who were waiting for work. These porters were predominantly enslaved men whose owners allowed them to work in urban Charleston with relative independence (see Episode No. 147). The number of enslaved people “hiring out” in the town reached such heights by 1751 that South Carolina’s provincial government began requiring enslaved porters to obtain an annual license and badge.[11] This license law, which was revised several times over the years, also created a board of commissioners to manage and maintain the streets of the provincial capital. After ratifying a revised version of the law in August of 1764, the “Commissioners for regulating and taking care of the Streets of Charles Town” resolved “that all negro porters and labourers that may be licenced, shall ply at the Curtain-Line, between the Watch-House and the gap opposite to Col. [Othniel] Beale’s house [now 95–101 East Bay Street], and not elsewhere.”[12]

Porters were routinely hired to load and unload ships docked at the nearby wharves, and to load and unload wagons, carts, and drays that carried goods through the town to and from the wharves.[13] The resolution of August 23rd, 1764, suggests that White citizens were annoyed by the daily presence of dozens of idle porters roaming the waterfront in search of work. The solution was to require them to congregate at a designated spot centered at the intersection of East Bay and Elliott Streets. Anyone wishing to hire a porter was obliged to visit that site, where they might find a crowd of Black men socializing and entertaining themselves while they waited for work.

Time: “About eight o’clock in the evening” of Tuesday, 2 December 1766.

The incident in question took place more than two hours after sunset very near the shortest day of the year. Almanacs of that era indicate that a waxing crescent moon hung low in the sky over Charleston, providing very little ambient light to illuminate the town. Oil-burning street lamps did not begin to appear on the urban landscape until the spring of 1770. The people congregating at the lower end of Elliott Street that evening stood in near complete darkness, therefore, and local custom was about to send them scrambling for shelter.[14]

The incident in question took place more than two hours after sunset very near the shortest day of the year. Almanacs of that era indicate that a waxing crescent moon hung low in the sky over Charleston, providing very little ambient light to illuminate the town. Oil-burning street lamps did not begin to appear on the urban landscape until the spring of 1770. The people congregating at the lower end of Elliott Street that evening stood in near complete darkness, therefore, and local custom was about to send them scrambling for shelter.[14]

From the first settlement of the town to February of 1865, civil authorities imposed a nightly curfew on the population of urban Charleston. This restrictive custom, which was derived from an ancient English practice, commenced with a nightly tattoo just after sunset and concluded with a morning reveille at dawn (see Episode No. 66). During the nocturnal hours, a paramilitary Night Watch perambulated through the streets to ensure that law-abiding citizens were safe within their homes. Enslaved people found on the streets after the tattoo were apprehended and detained in the Watch House until the following morning, when they would be bailed by their respective owners or whipped by civic authorities.

The hour of commencing the paramilitary watch in Charleston changed seasonally as the days grew shorter in the winter and longer in the summer. At the time of the “banjer” incident on the Bay in December 1766, the nocturnal Watch came on duty at eight o’clock in the evening. At or shortly before that hour, a drummer stood in front of the Watch House at the east end of Broad Street and beat a number of tunes to warn the population that the work day was ending. After the bells of St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s churches finishing chiming the hour, squads of White men carrying muskets with bayonets set out from the Watch House to clear the streets.[15]

The mass of people gathered at the “lower end of Elliott street” “about eight o’clock in the evening” of December 2nd, 1766, therefore, would have been on the verge of dispersing at any moment. The unidentified “banjer” player and his anonymous auditors, the majority of whom were undoubtedly enslaved people of African descent, stood just over a hundred feet to the south of the Watch House. Local law obliged them to congregate at this spot and empowered them to socialize freely during daylight hours, but their activities were as constrained by time as they were by location. When the armed watchmen stepped out of their headquarters and the tattoo began to beat, the melodious “banjer” gave way to the relative silence of a winter’s night.

Actor No. 1: “A gentleman.”

We might never know the identity of the man who reported the “banjer” incident of 1766, but we can distill a few clues from his published advertisement that help illuminate his point of view. The anonymous witness reportedly lost a leather “pocket book” or wallet lined with red silk, stuffed with paper money amounting to £255 in South Carolina’s provincial currency (around £36.8.10 sterling). This was a significant sum of money, nearly equal to the annual wages of a contemporary tradesman or musician working in urban Charleston. In addition, he reported the theft of “several orders, notes, accounts, and other papers” indicative of a typical man of business and relative affluence. The generous rewards offered for the return of his property underscores the value of the missing papers.[16]

We might never know the identity of the man who reported the “banjer” incident of 1766, but we can distill a few clues from his published advertisement that help illuminate his point of view. The anonymous witness reportedly lost a leather “pocket book” or wallet lined with red silk, stuffed with paper money amounting to £255 in South Carolina’s provincial currency (around £36.8.10 sterling). This was a significant sum of money, nearly equal to the annual wages of a contemporary tradesman or musician working in urban Charleston. In addition, he reported the theft of “several orders, notes, accounts, and other papers” indicative of a typical man of business and relative affluence. The generous rewards offered for the return of his property underscores the value of the missing papers.[16]

The text of his published advertisement alleged that an enslaved woman had picked the currency and papers from the large pockets of his fashionably-long coat or waistcoat. Curious readers of that era might have wondered what circumstances placed this “gentleman” in such close proximity to a woman of a radically different social caste. By noting that the alleged crime occurred “as he passed through a croud of negroes assembled at the lower end of Elliott-street, with a banjer playing,” the alleged victim pointed to a geographic, physical, and cultural context that his readers in urban Charleston would have immediately understood. The location in question was routinely crowded with enslaved porters waiting for work, and the presence of an African instrument probably attracted additional listeners from the local enslaved population. The White gentleman who described himself as a “sufferer” was not venturing into improper territory, therefore, but attempting to pass through a legitimate thoroughfare that just happened to be crowded with the bodies of his enslaved neighbors.

Actor No. 2: “A Negro wench.”

The anonymous man who described the scene in question stated that he suspected his pockets had been picked “by a negro wench, who rubbed herself very close to the sufferer.” The term “wench” is certainly pejorative, but it was commonly used by White writers of early South Carolina to describe adult Black women in general. After referring to her in this demeaning manner, the gentleman acknowledged that the woman’s appearance was “very remarkable,” or memorable, “having three or four strokes[,] the mark of her country, upon each cheek.” The “country marks” mentioned here refer to the sort of ritual scarification practiced by many of the cultural groups indigenous to West Africa. In their eyes, such permanent markings are badges of achievement, maturity, and family identity meant to be celebrated and admired. The texts of numerous runaway slave advertisements published in eighteenth century Charleston attest to the proliferation of “country marks” among the African population of the Lowcountry, but the practice of scarification apparently did not extend to enslaved children born in South Carolina.

The anonymous man who described the scene in question stated that he suspected his pockets had been picked “by a negro wench, who rubbed herself very close to the sufferer.” The term “wench” is certainly pejorative, but it was commonly used by White writers of early South Carolina to describe adult Black women in general. After referring to her in this demeaning manner, the gentleman acknowledged that the woman’s appearance was “very remarkable,” or memorable, “having three or four strokes[,] the mark of her country, upon each cheek.” The “country marks” mentioned here refer to the sort of ritual scarification practiced by many of the cultural groups indigenous to West Africa. In their eyes, such permanent markings are badges of achievement, maturity, and family identity meant to be celebrated and admired. The texts of numerous runaway slave advertisements published in eighteenth century Charleston attest to the proliferation of “country marks” among the African population of the Lowcountry, but the practice of scarification apparently did not extend to enslaved children born in South Carolina.

The White gentleman also noted the appearance of the woman’s teeth, which he described as being both “long” and “divided” or spaced. This description implies that the woman’s mouth was open as she passed within in his view—perhaps speaking to him or a neighbor, or smiling, or even singing along to the music of the “banjer.” In any case, her face was expressive, and her alleged contact with the White gentleman might have resulted from physical gestures associated with improvisatory dancing. The allegation of theft, therefore, might have stemmed from differing interpretations of the event in question. Was the African woman simply dancing enthusiastically within a crowded environment, or had she “rubbed herself very close” to the White gentleman in order to pick his pockets? Was she acting in concert with “accomplices” nearby, as the White “sufferer” implied in his advertisement? Unfortunately, such questions might forever remain a mystery.

Conclusion: The Sum of the Parts.

I hope you’ll agree with me that the process of expanding the latent clues with the 1766 “banjer” description helps us gain a better understanding of the time and place of an intriguing scene, and of the character of the people within earshot of the music. This exercise helps us sharpen our view of this community’s shared past, but it certainly doesn’t answer all of our questions. We might ponder, for example, whether the appearance of a “banjer” on the Bay in 1766 was an isolated event, or were banjo-like instruments heard on the streets of Charleston with some frequency during that era?

Considering the 1764 legal directive requiring enslaved porters to congregate on the Bay near the east end of Elliott Street, and considering that site’s proximity to the wharves that connected Lowcountry plantations to the port of Charleston, I believe the scene described in December 1766 was merely a snapshot of a routine phenomenon. The White gentleman who described the event mentioned the African instrument in passing, as if his readers were familiar with the context and did not require further explanation. The “banjer playing,” while interesting to modern readers, was, in his mind, peripheral to the more important narrative of his missing pocket-book. For all we know, the sounds of West African banjo–like instruments might have reverberated throughout urban Charleston on a daily basis. Facts related to this hypothesis and other mundane phenomena are now exceedingly rare, but this 1766 description provides a useful framework for imagining when, where, and how such forgotten music might have existed.

Considering the 1764 legal directive requiring enslaved porters to congregate on the Bay near the east end of Elliott Street, and considering that site’s proximity to the wharves that connected Lowcountry plantations to the port of Charleston, I believe the scene described in December 1766 was merely a snapshot of a routine phenomenon. The White gentleman who described the event mentioned the African instrument in passing, as if his readers were familiar with the context and did not require further explanation. The “banjer playing,” while interesting to modern readers, was, in his mind, peripheral to the more important narrative of his missing pocket-book. For all we know, the sounds of West African banjo–like instruments might have reverberated throughout urban Charleston on a daily basis. Facts related to this hypothesis and other mundane phenomena are now exceedingly rare, but this 1766 description provides a useful framework for imagining when, where, and how such forgotten music might have existed.

If you’re not familiar with the timbre of a traditional gourd banjo with gut strings, I encourage you to browse the Internet to find audio and video clips of modern instruments and players that revive the sounds of the distant past. Early-banjo enthusiasts are creating folk-music buzz around the world, and Charleston is part of that broad conversation. In my opinion, our history sounds sweeter when we recall that banjo-like instruments with African roots formed part of the soundtrack of early South Carolina, in both rural and urban settings.

[1] For more information about Robert Wells and his business, see David Moltke-Hansen, “The Empire of Scotsman Robert Wells, Loyalist South Carolina Printer-Publisher” (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 1984); Christopher Gould, “Robert Wells, Colonial Charleston Printer,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 79 (July 1978): 23–49.

[2] South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 5–12 December 1766 (Friday), No. 422, page 2. This notice also appeared in the subsequent edition of the same paper; see SCAGG, 12–19 December 1766 (Friday), No. 423, page 5.

[3] The latest scholarship regarding the African roots of the banjo can be found in Robert B. Winans, Banjo Roots and Branches (University of Illinois Press, 2018); and Scott V. Linford, “The ekonting in Jola culture and history,” Ethnomusicology Forum 28 (July 2019): 1–23.

[4] Dena J. Epstein, “The Folk Banjo: A Documentary History,” Ethnomusicology 19 (September 1975): 347–71.

[5] Johann David Schoepf, Travels in the Confederation 1783–1784, volume 2; translated by Alfred J. Morrison (Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1911), 261–62. Schoepf arrived in Charleston on 14 January 1784 and, after touring the Lowcountry, departed from the city on 9 March 1784; see pages 163–224 of this volume.

[6] See Susan P. Shames, The Old Plantation: The Artist Revealed. Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2010.

[7] In recent decades, a number of banjo enthusiasts around the world have focused attention on the African roots of the modern banjo. This interest has inspired a number of luthiers to create modern reproductions of the banjo-like instruments depicted in paintings and illustrations made during the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. From banjo maker Pete Ross in Maryland, for example, one can purchase a reproduction of the instrument depicted in the John Rose’s circa-1790 watercolor painting of “The Old Plantation” in South Carolina.

[8] While South Carolina’s infamous “Negro Act” of 1740 prohibited enslaved people from possessing or using drums, the officers of the Charleston militia routinely employed enslaved drummers for military exercises. This urban exception was confirmed by a legislative act of 1750 that prohibited “any negro or negroes to beat any drum or drums in the said town upon holydays or otherwise without the direction or permission of some officer either civil or military.” See section 36 of Act No. 670, “An Act for the better Ordering and Governing Negroes and other Slaves in this Province,” ratified on 10 May 1740, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 410; see section 29 of Act No. 775, “An Act for keeping the Streets in Charles Town clean, and establishing such other regulations for the security Health and Convenience of the Inhabitants of the said Town as are therein mentioned, and for establishing a new Market in the said Town,” ratified on 31 May 1750, the engrossed manuscript of which is held at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia.

[9] The banjo moved into the urban sphere of the United States during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, thanks to the meteoric popularity of so-called “minstrel” shows that featured White men in blackface-makeup performing parodies of contemporary Black culture. Through the influence of professional White minstrels performing across the country, the banjo evolved and infiltrated a number of different musical cultures. The instrument’s popularity waned in the early twentieth century when minstrel and vaudeville music fell out of fashion, but the banjo continued to thrive among the practitioners of bluegrass, country, and folk music that gained international attention during the second half of the twentieth century.

[10] For more information about this maritime topic, see Lynn B. Harris, Patroons & Periaguas: Enslaved Watermen and Watercraft of the Lowcountry (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2014).

[11] See section II of Act No. 787, “An additional and explanatory Act, to an Act of the General Assembly of this Province, intitled [sic], an Act for keeping the Streets in Charles-Town clean; and establishing such other Regulations for the Security, Health and Convenience of the inhabitants of the said Town, as are therein mentioned; and for establishing a new Market in the said Town,” ratified on 4 May 1751. The text of this act, like that of Act No. 775 above, was not included in the published Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but is found among the engrossed acts of the General Assembly at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia (SCDAH).

[12] On 10 August 1764, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified Act No. 927, “An Act to Empower Certain Commissioners therein mentioned, to keep clear and in good order and repair the streets of Charlestown; and for establishing other regulations in the said town,” which is transcribed in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 9 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1841), 697–705; South Carolina Gazette, 31 March–25 August 1764, No. 1550, page 3, “Rates of Carriage, as settled by the Commissioners for regulating and taking Care of the Streets of Charles Town, at a general meeting of the Board, held at the State-House, August 23, 1764.”

[13] For more information about wharf labor in early Charleston, see Michael D. Thompson, Working on the Dock of the Bay: Labor and Enterprise in an Antebellum Southern Port (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2015).

[14] Act No. 993, “An Act for a Fish Market; and for Preserving the Lamps in Charlestown,” ratified on 7 April 1770, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 9: 705–8.

[15] According to section II of Act No. 905, “An Act for the establishing, keeping and maintaining a Watch Company, for preserving good order and regulations in Charlestown,” ratified on 25 July 1761, the watch lasted “from eight of the clock in the evening, from the twenty-ninth day of September, to the twenty-fifth day of March, and from the twenty-fifth of March, to the twenty-ninth day of September, from nine of the clock in the evening, until the sun rising.” The text of this 1761 act was not included in the published Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but the engrossed manuscript is found at SCDAH, and the full text appears in Acts of the General Assembly of South Carolina, Passed in the Year 1761 (Charleston, S.C.: Peter Timothy, 1761), 9–17. The time-limited watch act of 1761 was prolonged by Act No. 936, “An Act to revive and Continue for the term therein limited, several Acts and clauses of Acts of the General Assembly of this Province,” ratified on 23 January 1765, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 4 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 206–10.

[16] By comparison, the contemporary organists at St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s churches in urban Charleston earned approximately £50 sterling per annum; see Nicholas Michael Butler, Votaries of Apollo: The St. Cecilia Society and the Patronage of Concert Music in Charleston, South Carolina, 1766–1820 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007, 75, 162.

NEXT: Five Years of Charleston Time Machine

PREVIOUSLY: Charleston’s Defensive Strategy of 1703

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments