The Baird Brothers: Charleston's Cycling Stars

Processing Request

Processing Request

May is National Bike Month, and I’d like to commemorate this annual event by turning back our calendars to the first golden age of bicycling in Charleston—the 1890s—and draw attention to the colorful careers of the celebrated Baird Brothers of Belfast and Charleston. If you don’t recognize the names of William John Baird and Isaac Baird, don’t worry, you’re not alone. We’ll begin our tour-de-histoire with a sprinting review of early bicycle history and get up to speed for the main course in fin-de-siècle Charleston.

The first bicycles appeared on the streets of Charleston in the spring of 1869, at which time the machine was general called a “velocipede,” after the Latin roots “veloci” (fast) + “pede” (feet). For about six months after the first velocipedestrian rolled through the streets of Charleston, the city experienced a case of bicycle fever. The machine, the steel steed, the feedless horse, as it was variously called, captured the public imagination and the attention of the newspaper press. The velocipede was still an awkward machine in 1869, however, and Charleston’s bicycle mania subsided in the later months of 1869. Of the next nineteen years, the bicycle continued to evolve as men tinkered with the shape, size, and mechanics of the machine in an ongoing effort to make it faster and more maneuverable. Throughout the 1870s and early 1880s, the most popular form was the “penny-farthing,” also called the “ordinary,” which featured a very large wheel in the front and a much smaller wheel in the back. Since the pedals were attached directly to the front axle, as on a modern tricycle, the over-sized front wheel was a means of achieving greater speed. The penny-farthing was dangerous and unstable, of course, but those dangers didn’t deter the young, adventurous men who formed the machine’s principal audience. Manufacturers and advertisers tried to portray the Victorian-era bicycle as a relaxing form of outdoor exercise, but in reality, cycling in this era was mostly a tough guy’s sport.

Everything changed in the late 1880s with the debut of the “safety” bicycle. Like the early velocipede, the safety bike featured two wheels of nearly equal size, which helped avoid accidents like flying over the handlebars (a common problem with the penny-farthing). The biggest improvement with the safety bike, however, was the use of a chain drive system. Rather than having pedals attached to the front axle, the pedals were now attached to a sprocket in the center of the frame that moved a chain that turned the rear axle. These features made the new safety bicycle more stable, more comfortable, and faster than any of its predecessors. Around the same time, around 1890, solid rubber bicycle tires appeared on the market, followed shortly thereafter by rubber “cushion” or “pneumatic” tires that used an inflatable inner-tube within a tough outer shell, just like we have today.

Safety bikes first appeared in Charleston in 1888, and “cushion” tires were here by 1891. By that time, the amateur sport of bicycle racing was already a global phenomenon that intrigued young men thirsty for speed and manly exercise. Most of the racing took place at regional meets, dominated in the United States by riders in the northeastern and midwestern states. Across the Atlantic Ocean, bicycle racing enjoyed a strong following throughout Europe in the 1890s, complete with trade journals and fan magazines in every language. This was a true golden age of cycling, in which the bicycle was embraced by children as well as ladies and gentlemen who cycled for pleasure, and avid young sportsmen who savored the rush of competitive speed. They shared the roads with horses and carriages, not gas-guzzling automobiles. This was the scene when the Baird brothers reached adulthood and settled in Charleston.

The Baird Brothers were born in the north of Ireland, in County Down, in the eastern suburbs of Belfast, to Hugh Baird and his wife, Jane Kirkwood Baird. William John Baird, better known as W. John or simply John, was born in 1866, and his brother, Isaac Baird, was born in 1868. John emigrated to the United States in 1883, at the age of seventeen, and settled in Charleston. Here he worked as a clerk at a shoe store in King Street run by William J. Yates, a merchant from the north of Ireland who may have been a relative. At the age of 22, John Baird became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1888. That same year, his twenty-year-old brother, Isaac Baird, emigrated to Charleston and began working as a clerk at Mr. Yates’ shoe store. According to the city directories of the late 1880s, both of the Baird Brothers worked at the shoe store at 370 King Street and slept upstairs at the same address.

At some point in their youth, either in Belfast or in Charleston, the Baird brothers caught the bicycle bug and became avid wheelmen. The safety bike debuted about the same time they reached adulthood, opening a new age of sport and commerce with a field wide open for competitors to make their mark. By 1890, there were at least a dozen safety bikes in Charleston and the beginnings of a competitive scene. By 1892, there were perhaps two hundred “safetys” in Charleston, and wheelmen here were just getting tuned into the burgeoning international racing scene. Late in the spring of 1892, twenty-four-year-old Isaac Baird returned to Ireland to complete in a series of long-distance amateur bicycle races. In road races of fourteen miles, twenty-five, fifty, and even one hundred miles, Isaac and his Ormond-brand racer swept first prize honors and set new record times to boot. In the one-hundred-mile race, riding over an unfamiliar course through country roads while carrying a paper map, Isaac got lost several times and gave up in frustration. After backtracking several miles, though, he managed to find the rest of the racers and get back on course. Restarting from the back of the pack, Isaac whizzed past everyone and finished the race in a record-breaking time of just over seven and a half hours.

At some point in their youth, either in Belfast or in Charleston, the Baird brothers caught the bicycle bug and became avid wheelmen. The safety bike debuted about the same time they reached adulthood, opening a new age of sport and commerce with a field wide open for competitors to make their mark. By 1890, there were at least a dozen safety bikes in Charleston and the beginnings of a competitive scene. By 1892, there were perhaps two hundred “safetys” in Charleston, and wheelmen here were just getting tuned into the burgeoning international racing scene. Late in the spring of 1892, twenty-four-year-old Isaac Baird returned to Ireland to complete in a series of long-distance amateur bicycle races. In road races of fourteen miles, twenty-five, fifty, and even one hundred miles, Isaac and his Ormond-brand racer swept first prize honors and set new record times to boot. In the one-hundred-mile race, riding over an unfamiliar course through country roads while carrying a paper map, Isaac got lost several times and gave up in frustration. After backtracking several miles, though, he managed to find the rest of the racers and get back on course. Restarting from the back of the pack, Isaac whizzed past everyone and finished the race in a record-breaking time of just over seven and a half hours.

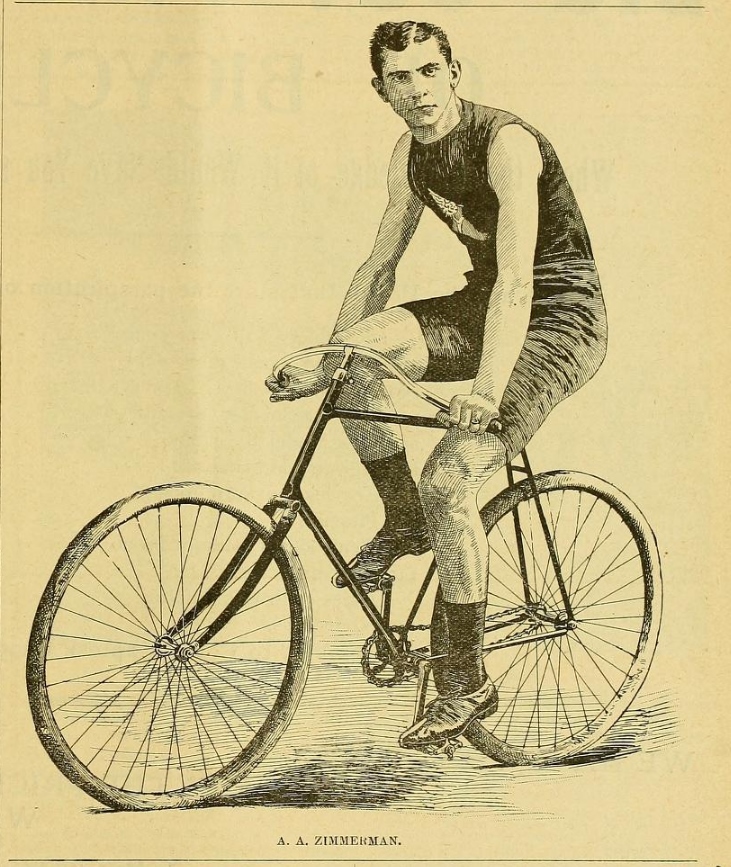

When he returned to Charleston in September 1892, Isaac Baird was an international figure mentioned in all the trade magazines of the day. Charleston’s small but enthusiastic cadre of wheelmen, as they called themselves, quickly built an oval race track (one-sixth of a mile around) at the northwest corner of Meeting and Sheppard Streets and held a regional amateur tournament. Isaac and John Baird were the men to beat, and they took home all the glory. In the early months of 1893, the Baird Brothers raced at Savannah’s fancy new track, and once again Isaac was out in front. The only man faster than “our own Isaac,” as the Charleston press called him, was the fastest cyclist in the world, Arthur “Zimmy” Zimmerman, who squeaked past the younger Baird in a series of matches at Savannah. Later in 1893, the Baird brothers scorched around the tracks at amateur meets in Columbia, then Atlanta, then Darlington. At the same time, the shoe-selling bicycle brothers also branched out on their own, opening a bicycle and shoe shop at on the east side of King Street, midway between John Street and Hutson Street. The Baird Brothers emporium at 422 King Street featured all the latest bicycle brands and gear, a bicycle reading lounge, a prominent but tasteful display of racing trophies, and a sensible and well-priced selection of men’s quality footwear.

In August 1893, the Baird Brothers and their fellow wheelmen were making preparations for another series of races at Charleston’s oval track later that autumn. All of those plans evaporated on the 28th of August, however, when a massive hurricane devastated the lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia and claimed several thousand lives. In the wake of that destructive, terrifying storm, the Baird brothers, like everyone else, concentrated their energies on recovering and rebuilding their lives. Racing seemed superfluous during those somber days, and Charleston’s oval race track fell into disuse and disrepair. The brothers expanded their shoe business and continued to sell bicycles, but their racing days were fading. In the summer of 1894, twenty-six-year-old Isaac Baird was no longer the fastest rider at the state bicycle meet in Columbia. In the summer of 1895, Isaac and his close friend, Robert McElree, a fellow Hibernian, sailed from Charleston to Ireland with the intention of competing in a series of amateur long-distance races. The Irish racers remembered “the Little Yankee” from Charleston, however, and had changed the rules since his last visit. A six-month residency was now required of all entrants, so little Isaac (five-foot seven inches tall, according to ship passenger records), was out of luck. Having crossed the Atlantic with his trusty Ormond racing bike, Isaac was not deterred. Unofficially, he raced anyway, just for the love of the sport.

Back in Charleston later in the winter of 1895–96, the Baird Brothers built a small circular riding track behind their King Street store, for the use of bicycle students who wanted to learn to ride away from public view. That summer, Isaac told a Charleston reporter that he estimated there were at least 3,000 bicycle owners in the city, with many additional riders renting or borrowing bicycles. Were there perhaps now more wheelwomen than wheelmen in Charleston? Probably not, Isaac replied, but the lady riders certainly do get more attention. Asked if he longed to resuscitate the big oval track in Charleston and race again, the twenty-eight-year-old Baird said he was tired of racing, and the cycling scene in Charleston was just too small to sustain the work. In fact, he had dismantled his old Ormond racer and used it for parts. Only the naked wheels hung on the wall of his bicycle shop as a reminder of his past glory days.

Back in Charleston later in the winter of 1895–96, the Baird Brothers built a small circular riding track behind their King Street store, for the use of bicycle students who wanted to learn to ride away from public view. That summer, Isaac told a Charleston reporter that he estimated there were at least 3,000 bicycle owners in the city, with many additional riders renting or borrowing bicycles. Were there perhaps now more wheelwomen than wheelmen in Charleston? Probably not, Isaac replied, but the lady riders certainly do get more attention. Asked if he longed to resuscitate the big oval track in Charleston and race again, the twenty-eight-year-old Baird said he was tired of racing, and the cycling scene in Charleston was just too small to sustain the work. In fact, he had dismantled his old Ormond racer and used it for parts. Only the naked wheels hung on the wall of his bicycle shop as a reminder of his past glory days.

After another trip to the Emerald Isle in the summer of 1897 with his friend, Robert McElree, Isaac Baird began to have second thoughts about abandoning the racing scene completely. At that moment, the bicycle industry was booming. International interest in recreational cycling and track racing had never been higher, and advances in manufacturing technology helped drive retail prices lower. The economic future of bicycling looked like a solid investment, and the Baird brothers, as a business team, were well-placed to capitalize on the market. During the winter of 1897–98, the brothers, Isaac and John, and their flat-mate, Robert McElree, hatched an idea to combine their collective business and sporting experience into a new venture. In the late spring of 1898, they chartered a new business, the Charleston Athletic Association, and announced their vision of a multi-purpose athletic park for all of Charleston to enjoy the healthful benefits of manly sports such as cycling, baseball, football, basketball, and tennis.

To finance this bold venture, the Baird Brothers and Robert McElree must have spent every penny they had, and perhaps mortgaged their business property on King Street as well. According to the city directories of the late 1890s and the federal census of 1900, the three single men were renting beds in a boarding house at 143 Calhoun Street—now the site of the Knights of Columbus Hall. Perhaps they were renting out the rooms above their retail space on King Street in an effort to make extra money. At any rate, in June 1898, the Baird brothers purchased a tract of six acres just within the northeastern corner of Charleston’s city limits, at the northeast corner of Meeting Street and Brigade Street. The property was bounded on the north by a cow pasture, and to the east by a railroad line. Here they spent approximately $15,000 developing a for-profit recreational complex that no one in Charleston remembers today.

Construction on the Baird Brothers’ Bicycle Park, as it became known, commenced in early June 1898. To make the park profitable, the brothers planned to sell memberships in the Athletic Association, and to charge a small admission fee to non-members. The first step, therefore, was to erect a nine-foot tall wooden fence around the entire six-acre park to prevent bystanders from enjoying the events for free. In the center of the property, they laid out an oval race track, thirty feet wide and one-third of a mile in circumference. The straightaways were described as being five hundred feet long, and the curved ends were banked eleven feet high to facilitate speedy turning. The foundation of the track itself was made of clay covered with five inches of packed coal cinders. It was intended to have a top dressing of Portland cement dust, but the Baird brothers decided to cover the entire track with tongue-and-groove wooden planks over a shallow wooden frame, slathered with creosote to make it waterproof. Adjacent to the track stood a wooden and brick grand stand measuring 150 feet long and forty feet tall, complete with showers, changing rooms, and lockers below for competitors and members of the Charleston Athletic Association. The grand stand, designed by local architect A. W. Todd, could accommodate 1,100 seated spectators, and a stand of bleachers were designed to seat a further one thousand general-admission ticket holders.

Construction on the Baird Brothers’ Bicycle Park, as it became known, commenced in early June 1898. To make the park profitable, the brothers planned to sell memberships in the Athletic Association, and to charge a small admission fee to non-members. The first step, therefore, was to erect a nine-foot tall wooden fence around the entire six-acre park to prevent bystanders from enjoying the events for free. In the center of the property, they laid out an oval race track, thirty feet wide and one-third of a mile in circumference. The straightaways were described as being five hundred feet long, and the curved ends were banked eleven feet high to facilitate speedy turning. The foundation of the track itself was made of clay covered with five inches of packed coal cinders. It was intended to have a top dressing of Portland cement dust, but the Baird brothers decided to cover the entire track with tongue-and-groove wooden planks over a shallow wooden frame, slathered with creosote to make it waterproof. Adjacent to the track stood a wooden and brick grand stand measuring 150 feet long and forty feet tall, complete with showers, changing rooms, and lockers below for competitors and members of the Charleston Athletic Association. The grand stand, designed by local architect A. W. Todd, could accommodate 1,100 seated spectators, and a stand of bleachers were designed to seat a further one thousand general-admission ticket holders.

In the summer of 1898, the Baird brothers were clearly anticipating big crowds at their new athletic park, and the local press took notice. Didn’t a similar venture in 1892 fail, and didn’t Isaac Baird say back in the summer of 1896 that Charleston wasn’t ready for a race track? In retrospect, Isaac Baird told a reporter in August 1898, the construction of a bicycle track back in 1892 had been “the veriest nonsense.” There simply weren’t enough cyclists in Charleston at that time to sustain such an expensive venture. Things had changed in the past six years, though, and now Isaac estimated that there were nearly 4,500 bicycle owners in the city. Cycle racing, both on the road and on oval tracks, was now a fixture of the athletic world, and he was certain that the people of Charleston would fall in love with the sport if only it were available within easy reach. “I feel safe in predicting an outpour of people to attend the races such as never before has been seen at any event before in this city,” said Isaac. “In view of this fact, as it appeared individually to me as well as my brother, we conceived the idea that in lending a helping hand in the way of laying a track and building a grand stand we could be furthering a fine sport, that had been sadly neglected in this city.”

The Baird Brother’s Bicycle Park opened on October 26th, 1898, with a three-day regional meet that attracted crack riders from around the state. Although experts in the business pronounced the new track to be one of the best in the country, the size of crowds left much to be desired. The local press reported that the Bairds were “by no means discouraged,” however, and they continued to “believe that the prospects for Charleston becoming a great bicycle race town are as good as those of any city in the South. Bicycle racing is new to the people and like everything else the people have to be educated to attending the races.” Another racing meet in mid-November attracted only “a very slim crowd,” however. During the winter of 1898–99, the brothers laid out a football gridiron in the center of the bicycle track, and planted hundreds of trees around the perimeter to develop shade for the expected summer crowds. Ladies were now admitted free of charge, and some female cyclists were seen riding the oval track for fun.

In May 1899, during Charleston’s massive reunion of Confederate veterans, the Baird brothers mounted another series of bicycle events for both amateur racers and novices. There was even a bicycle competition to determine the fastest Confederate veteran, which must have been an amusing sight, some thirty-four years after the end of our Civil War. Despite the exciting sport and novelty on the program, and the presence of a brass band to enliven the scene, the crowds did not come. In July 1899, the Bairds again extended their business by purchasing No. 424 King Street, the building adjacent to their bicycle and shoe store, which some unknown party tried to burn down on the night of July 25th. Their next bicycle racing meet in late October 1899 again drew crack riders from across the state, but once again the public didn’t pay much attention. One year after opening their expensive park, it was becoming clear that the Baird brothers had overestimated Charleston’s appetite for cycling, and for sport in general.

In May 1899, during Charleston’s massive reunion of Confederate veterans, the Baird brothers mounted another series of bicycle events for both amateur racers and novices. There was even a bicycle competition to determine the fastest Confederate veteran, which must have been an amusing sight, some thirty-four years after the end of our Civil War. Despite the exciting sport and novelty on the program, and the presence of a brass band to enliven the scene, the crowds did not come. In July 1899, the Bairds again extended their business by purchasing No. 424 King Street, the building adjacent to their bicycle and shoe store, which some unknown party tried to burn down on the night of July 25th. Their next bicycle racing meet in late October 1899 again drew crack riders from across the state, but once again the public didn’t pay much attention. One year after opening their expensive park, it was becoming clear that the Baird brothers had overestimated Charleston’s appetite for cycling, and for sport in general.

The turn of the twentieth century came quietly to the Bairds’ bicycle enterprise. They presented no competitive races in the year 1900, although their athletic park, surrounded by a nine-foot wooden fence, continued to be open to members and ladies in general. I haven’t found much information about what the brothers were doing at this time, but something had definitely changed. Isaac and John were still renting cots at the boarding house with their friend, Robert McElree, and all three continued their retail operations at 422 and 424 King Street. In late September 1900, William John Baird married Maggie Walker at her parents’ house and soon settled into a rented house of their own. Isaac’s close friend Robert McElree became ill and died in May 1901 at the age of forty-two. A few months later, John and Maggie’s first child, Hugh Baird, was born. Increasingly, Isaac was on his own and becoming jaded. As he told a reporter in December 1900, the bicycle was here to stay, but the future belonged to motor machines. The industry was in its infancy, of course, but the veteran cyclist predicted that his fellow racers would soon abandon their pedal-powered machines for the new-fangled motorcycles and automobiles.

After nearly two years of inactivity, the race track at the Baird Brothers Park roared back to life in the autumn of 1901. Perhaps Isaac was determined to make a final stab at success in the cycling world. He renovated and refurbished the park, and between September and November organized a number of regional match races that brought all the latest big names of the southeast to Charleston. To increase their audience, the Bairds’ bicycle tournaments alternated days of white-only races and days of “colored” races. Each of these segregated events featured the same sorts of races and awarded exactly the same prizes to the respective winners. To facilitate racing in the after-work hours, the Bairds also rented electric arc lights and installed torches to illuminate the riders under the autumnal moon. Despite these efforts, however, the crowds Isaac had predicted in 1898 never materialized. As business men now in their thirties, and one with a growing family, it became clear that their big investment would never pay off. It was time to make a change.

Isaac Baird made a trip to Ireland in the summer of 1902, apparently on a mission to investigate the business prospects in their native Belfast. A gala week of races took place at the Baird Brothers’ Bicycle Park in late October of that year, but it was their last hurrah. In November 1902, they sold one of their properties on King Street and began planning an exit from business in Charleston. Their last event at the bicycle park was held on the first day of January 1903 and proved to be an epoch-changing event. Instead of athletic men pedaling frantically around the oval track, the Baird’s farewell event was an exhibition match between four motorcycles from Savannah—named the “Black Imp,” the “White Ghost,” the “Red Devil,” and the “Indian.” These names were meant to sound menacing and dangerous, of course, but if you look online at a photo of a 1903 motorcycle, you’ll see that it’s nothing more than a standard safety bicycle with a small engine bolted to the center of the frame. Nevertheless, the gasoline-powered motorcycle represented the future of racing and transportation in Charleston and elsewhere. The golden age of the bicycle in the 1890s was now well and truly gone.

Isaac Baird made a trip to Ireland in the summer of 1902, apparently on a mission to investigate the business prospects in their native Belfast. A gala week of races took place at the Baird Brothers’ Bicycle Park in late October of that year, but it was their last hurrah. In November 1902, they sold one of their properties on King Street and began planning an exit from business in Charleston. Their last event at the bicycle park was held on the first day of January 1903 and proved to be an epoch-changing event. Instead of athletic men pedaling frantically around the oval track, the Baird’s farewell event was an exhibition match between four motorcycles from Savannah—named the “Black Imp,” the “White Ghost,” the “Red Devil,” and the “Indian.” These names were meant to sound menacing and dangerous, of course, but if you look online at a photo of a 1903 motorcycle, you’ll see that it’s nothing more than a standard safety bicycle with a small engine bolted to the center of the frame. Nevertheless, the gasoline-powered motorcycle represented the future of racing and transportation in Charleston and elsewhere. The golden age of the bicycle in the 1890s was now well and truly gone.

In February 1903, the Baird brothers sold their entire stock of bicycle goods to a competitor, and in April put their King Street retail property on the market. During the summer of 1903, the Bairds constructed twenty-three cottages on the fringes of their Bicycle Park property, each containing only three rooms, and tried to market them to working-class folk. When that venture didn’t immediately yield a profit, the brothers sold the entire six-acre property in October 1903. In the spring of 1904, Isaac and William John Baird, along with John’s growing family, packed up and moved to Belfast. There they opened a boot and shoe store that specialized in retailing American-made products. Their business flourished, and they eventually opened satellite stores in Belfast and Dublin.

After leaving Charleston in 1904, Isaac and John returned to the United States many times over the next twenty-odd years, often venturing to New York two or three times a year to conduct business with American suppliers. From time to time, they returned to Charleston to visit friends and Maggie Walker Baird’s family. Her son, Hugh Baird, returned to Charleston to become a Citadel cadet, and graduated with the class of 1923. I haven’t been able to find any information about the passing of Isaac Baird or his older brother, William John, but someone out there surely knows. If you have any information about the family, please let us know here at CCPL.

As for the Baird Brothers’ Bicycle Park at the northeast corner of Meeting and Brigade Streets, it’s now a highly developed commercial site. Morrison Drive, created in the 1950s, now cuts a diagonal swath through the center of the old bicycle track, so there’s a good chance you’ve driven your automobile or ridden your bike though the site of Charleston’s most ambitious bicycle venture to date. In honor of National Bike Month, and in commemoration of the fabulous Baird brothers of Belfast and Charleston, I invite you to pedal up Meeting Street to that site and raise a jar in their honor. Today’s cycling scene is all the richer for their ambitious efforts, even though few in this city remember their names.

As for the Baird Brothers’ Bicycle Park at the northeast corner of Meeting and Brigade Streets, it’s now a highly developed commercial site. Morrison Drive, created in the 1950s, now cuts a diagonal swath through the center of the old bicycle track, so there’s a good chance you’ve driven your automobile or ridden your bike though the site of Charleston’s most ambitious bicycle venture to date. In honor of National Bike Month, and in commemoration of the fabulous Baird brothers of Belfast and Charleston, I invite you to pedal up Meeting Street to that site and raise a jar in their honor. Today’s cycling scene is all the richer for their ambitious efforts, even though few in this city remember their names.

PREVIOUS: The Rebellion of South Carolina: April 21st, 1775

NEXT: The Medieval Roots of the Charleston Night Watch

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments