The Advent of Black Suffrage in South Carolina

Processing Request

Processing Request

Modern conversations about the legacy of voter discrimination in South Carolina politics tend to focus on the civil-rights struggles of the mid-twentieth century, but the roots of this important issue lie much deeper in the past. Founded on imported traditions of exclusion, our colonial and state governments empowered a white male minority to define the boundaries of participation. The long campaign to establish the right for black men to vote in South Carolina finally succeeded in 1867, but that seminal event sparked a racially-charged backlash that reverberated through the generations to the present.

The right to vote, also known as suffrage, is an essential element of democracy in the United States and in any true republic. It entitles citizens to express their individual opinions and values by participating in the selection of the representatives who form their government. Allowing citizens to express such opinions and choices freely is a prerequisite for building a just and equitable society. Despite the fundamental nature of suffrage, the history of voting in the United States is colored by a deep legacy of prejudice and discrimination. Here in 2020, for example, Americans are celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which finally secured the right of suffrage to the women of this nation in 1920. At the same time, our country mourns the recent loss of United States Representative John Lewis, who was a Civil Rights pioneer in the 1960s. Rev. Lewis’s work, combined with that of many other courageous advocates during that troubled era, led to the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965. That Federal law abolished various practices long used in the Southern states to deter Americans of African descent from voting.

The practice voter discrimination is not simply a historical footnote in the narrative of American elections, however. It’s a deeply-rooted, systemic legacy that continues to play a role in local, state, and national politics today, and probably will endure into the foreseeable future. In a controversial 2013 decision, for example, the United States Supreme Court struck down some of the Federal oversite provided in the 1965 Voting Rights Act. This action has caused some political advocates to worry about the future implications of this change. As we head towards election season this fall, many people in the U.S. Capitol and across the nation are once again talking about the importance of removing obstacles that might prevent or deter the participation of legally-qualified voters. Some lawmakers in Washington are advocating for the passage of a new bill to strengthen the protections created in 1965, while others view such measures as antiquated and unnecessary in the twenty-first century. Conversations about this topic inevitably contain references to the long legacy of voter suppression in the Southern states, including South Carolina, as a testament to the continued need for Federal protection of voting rights. Unless you have a particular affinity for reading about the turbulent racial politics of the late nineteenth-century, you might be wondering what the big fuss is all about.

To participate in this important debate, it helps to know a bit about the general history of suffrage and, more specifically, the early history of black voting in South Carolina. It’s not a pleasant story, and parts of the narrative are quite gruesome. As we celebrate the 350th anniversary of the Palmetto State, we must acknowledge that the outcome of all elections during the first three centuries of voting in South Carolina was influenced by legally-sanctioned practices of limited suffrage and voter suppression. The phrase “limited suffrage” refers to the practice of restricting the right to vote to a legally-prescribed segment of the population. All elections held during the first 250 years of South Carolina’s history, from 1670 through 1920, for example, were characterized a policy of limited suffrage that excluded all women. For the first 196 years of elections in the Palmetto State, up to 1867, voting limits were also drawn along a color line informed by the fictional construct of racial differences. The phrase “voter suppression,” on the other hand, refers to a number of practices intended to influence the outcome of elections by discouraging or preventing qualified voters from casting their ballots or fraudulently preventing legitimate votes from being counted. Anecdotal evidence of voter suppression appears sporadically in the documentary record of early South Carolina, but it became a consistent and significant feature of the state’s political culture shortly after the conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865. From that time until the 1960s, the electoral process in South Carolina was tainted by widespread policies of discouragement, fraud, intimidation, and even violence that were designed to suppress the participation of black voters and perpetrated by both criminal means and practices defined by state law.

To participate in this important debate, it helps to know a bit about the general history of suffrage and, more specifically, the early history of black voting in South Carolina. It’s not a pleasant story, and parts of the narrative are quite gruesome. As we celebrate the 350th anniversary of the Palmetto State, we must acknowledge that the outcome of all elections during the first three centuries of voting in South Carolina was influenced by legally-sanctioned practices of limited suffrage and voter suppression. The phrase “limited suffrage” refers to the practice of restricting the right to vote to a legally-prescribed segment of the population. All elections held during the first 250 years of South Carolina’s history, from 1670 through 1920, for example, were characterized a policy of limited suffrage that excluded all women. For the first 196 years of elections in the Palmetto State, up to 1867, voting limits were also drawn along a color line informed by the fictional construct of racial differences. The phrase “voter suppression,” on the other hand, refers to a number of practices intended to influence the outcome of elections by discouraging or preventing qualified voters from casting their ballots or fraudulently preventing legitimate votes from being counted. Anecdotal evidence of voter suppression appears sporadically in the documentary record of early South Carolina, but it became a consistent and significant feature of the state’s political culture shortly after the conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865. From that time until the 1960s, the electoral process in South Carolina was tainted by widespread policies of discouragement, fraud, intimidation, and even violence that were designed to suppress the participation of black voters and perpetrated by both criminal means and practices defined by state law.

South Carolina’s widely-acknowledged history of civil inequity formed part of the motivation behind the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965. That Federal law was supposed to eradicate forever the traditions of denying or discouraging certain members of the population from exercising their right of suffrage, but vestiges of past abuses continue to reverberate in our present political landscape. As conscientious citizens, it’s incumbent on us to learn about the mistakes of the past to avoid repeating them in the present and future. We could talk about the various campaigns of violence, intimidation, and fraud that marred South Carolina elections from the 1870s to the 1960s, but I’d like to offer a prelude to that future conversation and draw your attention to the crux of the issue. The rise of both improvised and systemic voter suppression in South Carolina was triggered by one seemingly simple event: the advent of black voting. The struggle for black suffrage was, of course, part of the larger efforts to secure civil rights in general for Americans of African descent. That long and contentious campaign culminated in the American Civil War that defeated the powers that sought to hold black Americans in a state of perpetual servitude. Remember, however, that neither the conclusion of the war in 1865 nor the subsequent ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibits slavery, empowered black men to participate in the electoral process. The specter of voter suppression arose in reaction to the advent of black voting. To understand the context of that important moment in South Carolina history, let’s review quickly the story of suffrage in the early years of the Palmetto State.

Following traditional English practices in colonial-era South Carolina, only white Protestant men owning a certain minimum amount of property were fully enfranchised—that is, considered free citizens and allowed to vote. The poorest of white men, women in general, and all people of African descent (who formed the majority of the population by 1708), were therefore legally disenfranchised, or barred from voting, in early South Carolina. Such was the general practice across the American colonies and the early United States, and few contested the inequality of this long-held tradition of limited suffrage. South Carolina’s revised state constitution of 1790 finally recognized the legal citizenship of non-Protestants. In 1810, the state legislature adopted a policy of “universal suffrage” that allowed all white males aged twenty-one and above to vote without qualifications regarding wealth, property, or level of education. That policy was considered progressive at the time, but national standards soon caught up with the Palmetto State. By the time of the American Civil War, 1861–65, most states granted suffrage to white males regardless of their wealth or education.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, South Carolina’s political arena hosted a number of distinct parties and factions that all shared a number of common tenets. Their commitment to conservative social and political values coalesced under the banner of the Democratic Party in the years leading up to the Civil War. Differences of opinion about the role of the Federal government in Southern politics created a divide between Unionist Democrats and States Rights Democrats, but both sides of the Democratic coin at that time were generally united by their firm belief in the natural superiority of white men over the rest of the population, especially over the enslaved black majority. In contrast to these conservative tenets, the Republican Party of the mid-nineteenth-century espoused a more liberal recognition of civil rights and favored the abolition of slavery. For these reasons, among others, the Republican party was effectively non-existent in the Southern slave-holding states in the years leading up to the American Civil War. All of the states that seceded from the national Union in 1861 were dominated by conservative Democrats who were stridently opposed to the more liberal Republicans who held sway up North and out West.

Any attempt to compare the American political landscape of the nineteenth century with the present runs into the strange conundrum of nomenclature. The broad generalizations I’ve just made about the Democratic and Republican parties are confined to a historical past that is separate and distinct from the present political scene. Over a period of several decades spanning the middle of the twentieth century, the Democratic Party became increasingly liberal and the Republican Party became more conservative. By the latter years of the twentieth century, the two parties had effectively switched sides. This political flip-flop invariably sparks confusion whenever we compare the present political scene with that of the distant past, and it’s important to recognize the differences. Republicans in twenty-first-century America, for example, occasionally identify themselves as members of “the Party of Lincoln,” but this description is misleading. While it is true that President Abraham Lincoln was strongly affiliated with the Republican Party during the 1850s and 1860s, the liberal policies and values espoused by the Republican Party of Lincoln’s era were diametrically opposed to the conservatism endorsed by the Republican Party of the present. To highlight the historical contrast between the principal political parties active in post-Civil War South Carolina, therefore, I’m going to use the terms “conservative Democrat” and “liberal Republican” for the remainder of this conversation.

Any attempt to compare the American political landscape of the nineteenth century with the present runs into the strange conundrum of nomenclature. The broad generalizations I’ve just made about the Democratic and Republican parties are confined to a historical past that is separate and distinct from the present political scene. Over a period of several decades spanning the middle of the twentieth century, the Democratic Party became increasingly liberal and the Republican Party became more conservative. By the latter years of the twentieth century, the two parties had effectively switched sides. This political flip-flop invariably sparks confusion whenever we compare the present political scene with that of the distant past, and it’s important to recognize the differences. Republicans in twenty-first-century America, for example, occasionally identify themselves as members of “the Party of Lincoln,” but this description is misleading. While it is true that President Abraham Lincoln was strongly affiliated with the Republican Party during the 1850s and 1860s, the liberal policies and values espoused by the Republican Party of Lincoln’s era were diametrically opposed to the conservatism endorsed by the Republican Party of the present. To highlight the historical contrast between the principal political parties active in post-Civil War South Carolina, therefore, I’m going to use the terms “conservative Democrat” and “liberal Republican” for the remainder of this conversation.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, agents of the U.S. Army in Charleston and across the South began supervising the work of restoring order and re-establishing a sense of normalcy. This was the beginning of a long process of rehabilitation and reconciliation between the rebellious Confederate States and the old Federal union of the United States known as the era of “Reconstruction.” Historians of this turbulent era frequently articulate a distinction between Presidential (or “Provisional”) Reconstruction in the years immediately after the end of the war and a longer period of Congressional (or “Radical”) Reconstruction that endured from 1867 to 1877. The main distinction between these eras was the identity and party affiliation of the men holding the reins of power.

During the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson appointed a Unionist Democrat, Benjamin Perry, to serve as provisional governor of South Carolina and to lead the state’s efforts to form a new civilian government with an agenda of Federal requirements. Perry immediately called for the election of delegates to form a convention to craft an interim state constitution. Following time-honored practices, the state-wide election of 1865 was limited to the participation of white men who selected a slate of recent rebels and conservative men who represented the “old guard” intimately familiar with South Carolina’s exclusionary political traditions. The convention assembled in Columbia in September and quickly ratified a constitution establishing a conservative, traditional framework for a new state government. A series of fresh elections across South Carolina, again limited to the participation of adult white men, produced an all-white, Democratic legislative body that in October began crafting a new political machine for the state while simultaneously working to fulfill the Federal requirements prescribed by President Andrew Johnson. The legislature dutifully adopted a resolution acknowledging the end of slavery and ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but then crafted a series of new laws designed specifically to restrict and control the rights and abilities of African Americans in South Carolina. These overtly discriminatory laws, which became known as the “Black Code,” demonstrated that the state’s provisional white legislature was unwilling to acknowledge that formerly-enslaved people had a right to full citizenship. Critics everywhere decried this perpetuation of the paternalistic “vestiges of serfdom,” while the conservative Democratic legislature expressed no shame in limiting the civil liberties of the majority of South Carolinians.

The military commander superintending South Carolina nullified the “Black Code” in January 1866, while the United States Congress considered more stringent methods of reforming the governments of the formerly rebellious states. On April 9th, 1866, the U.S. Congress ratified a law that became known as the “Civil Rights Act” of 1866, which formed a major step in securing the legal right to citizenship to all native-born Americans, regardless of their race, color, or former condition. Two months later, Congress approved and distributed for ratification the text of a 14th Amendment to the Constitution which identified all native-born Americans as citizens, endowed all male citizens (age 21 and above) with the right to vote, and promised to all people equal protection under the law.

In the autumn of 1866, South Carolina was at a political crossroads. The provisional legislature convened in Columbia and reviewed its task of reforming the state’s government to conform to the requirements outlined by President Johnson. In the spirit of compromise, the white, conservative legislature was willing to revise the laws known pejoratively as the “Black Code,” but they balked at the text of the proposed 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The rationale behind this obstinance was expressed plainly in scores of newspaper editorials published across the state during that time. The white, conservative Democratic leaders of South Carolina refused to allow formerly-enslaved men the right to vote and refused to acknowledge the equality of all citizens. On December 20th, 1866, at the end of its legislative season, the South Carolina General Assembly officially rejected the new amendment. In fact, the provisional governments of all of the former Confederate States (except Tennessee) rejected the proposed 14th Amendment. Back in Washington, D.C., this mass refusal was the last straw in an increasingly stressful political situation.

When the United States Congress convened in Washington in early 1867, the principal topic of debate was the recalcitrance of the Southern states. President Johnson had already outlined for each of the former Confederate states a reasonable path to re-admission in the Union, but their progress was slow and less than satisfactory. In order to motivate the rebellious states to mend their ways, Congress decided, more aggressive, or “radical” means were necessary. On March 2nd, 1867, the United States Congress ratified “An Act to Provide for the More Efficient Government of the Rebel States.” In the newspapers of 1867, this law was sometimes called the “Admission Act” because it outlined a new list of actions required of each of the “rebel” states before they would be readmitted to the Union, but most historians now refer to it as the “Reconstruction Act.” (Actually, it was amended three times by supplemental laws passed on 23 March 1867, 19 July 1867, and 11 March 1868). The Reconstruction Act of March 1867 was the first step in a new era of post-war politics that became known as Congressional Reconstruction, or “Radical” or “Military” Reconstruction.

Sweeping aside the past two years of “provisional” reconstruction, Congress declared that “no legal state government” existed in any of the Southern states (except Tennessee), and divided the South into five military districts, each to be administered by a U.S. military commander. (North and South Carolina together formed U.S. Military District No. 2). The entirety of the South (except Tennessee) was to live under martial law until the states met the following benchmarks: All male citizens, regardless of race, color, or former condition (except certain ex-Confederate leaders) must be permitted to elect delegates to participate in new state constitutional conventions. The new state constitutions must provide for universal male suffrage, and the said constitutions had to be approved by the U.S. Congress. Finally, each of the states had to ratify the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. When each of the formerly rebellious states had completed all of these tasks, the president would consider readmitting them to the Union.

As this Federal law was disseminated across the Southern states, another political movement was afoot in Charleston. Beginning in March 1867 and continuing into July, a series of public meetings in this city and in Columbia led to the formation of the Republican Party of South Carolina. This liberal organization, the party of the late Abraham Lincoln, was a new phenomenon in the South. Although white men dominated the Republican Party in the Northern and Western states, formerly-enslaved men quickly formed a Republican majority in the formerly-rebellious Southern states. Their numbers in South Carolina were augmented by men of African descent who had once been “free persons of color,” as well as a handful of liberal-minded white men. The rise of the black-majority Republican Party in the Palmetto State elicited frank expressions of contempt and revulsion from the vast majority of the state’s conservative white Democrats. This political sea-change also inspired a new vocabulary of racially-charged pejorative epithets. White-owned newspapers across the South regularly described formerly-enslaved Republicans as “native Negroes”; black and white Northerners who came down to assist or “interfere” in Southern politics were called “carpetbaggers”; white Southerners who allied themselves with the black majority were maliciously lambasted as “scalawags.”

As this Federal law was disseminated across the Southern states, another political movement was afoot in Charleston. Beginning in March 1867 and continuing into July, a series of public meetings in this city and in Columbia led to the formation of the Republican Party of South Carolina. This liberal organization, the party of the late Abraham Lincoln, was a new phenomenon in the South. Although white men dominated the Republican Party in the Northern and Western states, formerly-enslaved men quickly formed a Republican majority in the formerly-rebellious Southern states. Their numbers in South Carolina were augmented by men of African descent who had once been “free persons of color,” as well as a handful of liberal-minded white men. The rise of the black-majority Republican Party in the Palmetto State elicited frank expressions of contempt and revulsion from the vast majority of the state’s conservative white Democrats. This political sea-change also inspired a new vocabulary of racially-charged pejorative epithets. White-owned newspapers across the South regularly described formerly-enslaved Republicans as “native Negroes”; black and white Northerners who came down to assist or “interfere” in Southern politics were called “carpetbaggers”; white Southerners who allied themselves with the black majority were maliciously lambasted as “scalawags.”

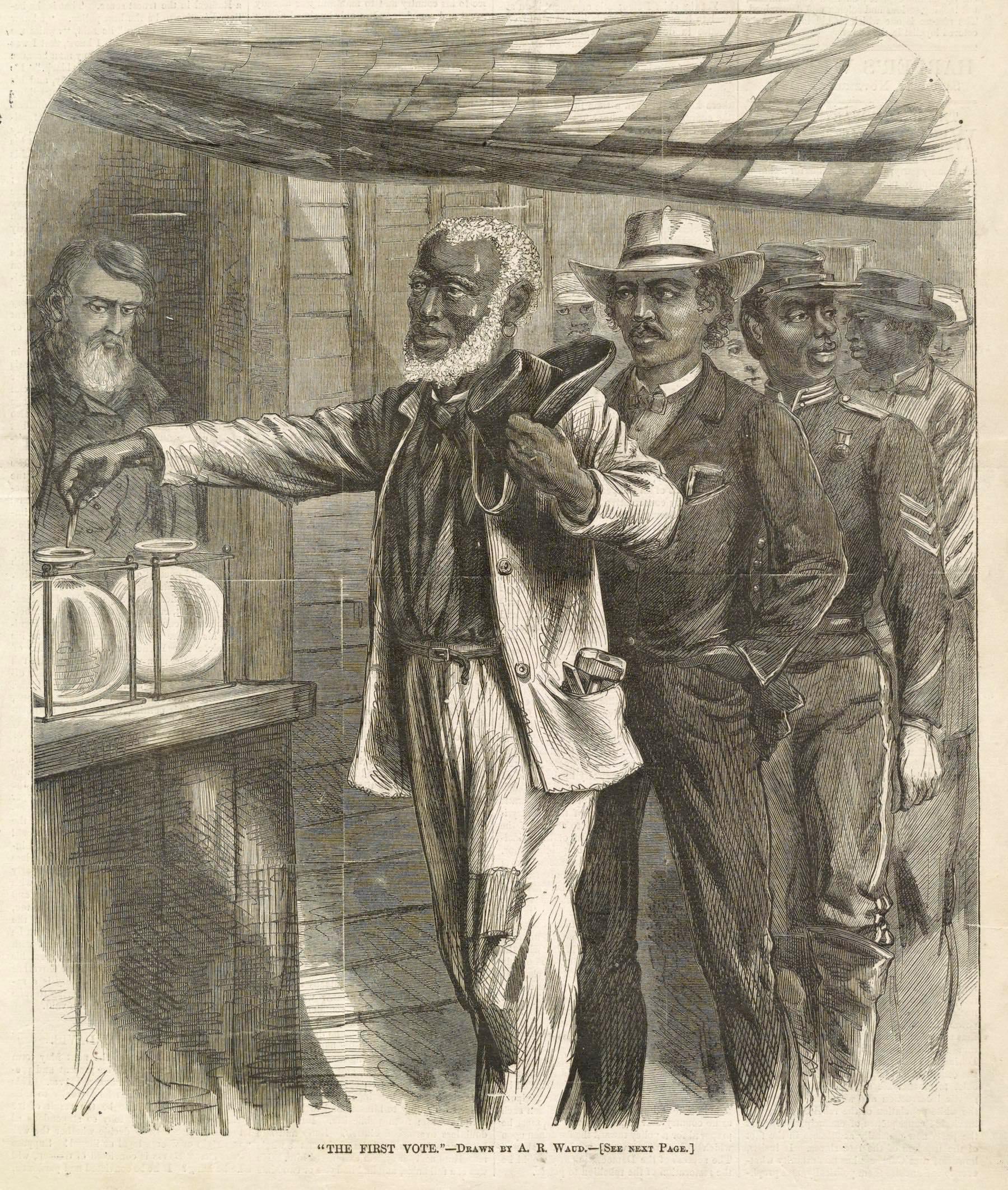

The Congressional Reconstruction Act of March 1867 triggered the rise of the Republican Party of South Carolina, and by the end of the summer it was a functioning political machine. The timing was fortuitous, but not coincidental. Everyone knew that elections would soon be held to form a new constitutional convention and lay the foundation for a new state government. Newly-enfranchised black voters across the state quickly organized into local and regional units or “leagues” and prepared to exercise their Constitutional right to suffrage. On October 16th, the U.S. military commander in control of South Carolina announced the upcoming election date, and voters across the state scrambled to register. On November 19th and 20th, 1867, voters went to the polls to vote “For a Convention” or “Against a Convention.” Those who voted in favor of a convention were also asked to select delegates from their respective voting districts. This was a momentous occasion in South Carolina—the first election in which men of African descent were allowed to participate. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of the voters were liberal Republicans who voted for a convention. They also elected 124 delegates from across the state, most of whom were formerly-enslaved men of African descent, and commenced planning for a grand assembly in mid-January.

The South Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1868 concluded in mid-March and then asked citizens to approve its work. A large majority of the state’s qualified voters (predominantly black Republicans) endorsed the new constitution in April, and the U.S. Congress ratified the document that May. The Constitution of 1868 was a remarkable achievement in the history of the Palmetto State. For the first time, the law of the land acknowledged the civil rights of all native-born citizens and extended the right of suffrage to all adult males, regardless of their race, color, former condition, wealth, or level of education. A few years ago, I recorded a podcast about this topic in conjunction with the 150th anniversary of the Constitution of 1868 (see Episode No. 55), so I’ll resist the temptation to say more about that important document.

Not everyone appreciated such radical changes to the state’s political traditions in 1868, of course. Across South Carolina, members of the conservative white minority expressed contempt for the new political machinery that empowered the formerly-enslaved black majority. The combined force of the Federal Reconstruction Act of 1867, the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and the state Constitution of 1868 upended two centuries of white supremacy and black subservience in South Carolina. As voters elected more and more black Republicans to a variety of local, state, and federal offices, white conservative Democrats grew increasingly frustrated and angry. Their desire to re-establish traditions of white supremacy attracted few black voters as long as Democrats adhered to the rules of law and order. Their solution for regaining political power, therefore, was to step outside the bounds of civil discourse.

In reaction to the advent of black suffrage in South Carolina in 1867, many white conservatives felt compelled to circumvent the legitimate political process in order to engineer a return to power. Between 1868 and 1877, the people of South Carolina and other Southern states witnessed a proliferation of illegal activities designed to undermine the political influence of the liberal Republican Party. Under the guise of restoring law and order (in terms defined by a belief in white supremacy), conservative Democrats used fraud, intimidation, violence, and even murder to influence or suppress the votes of their political rivals. Their methods were improvised and sporadic at first, but throughout the 1870s became increasingly organized and efficient. Both the collapse of Federal Reconstruction in 1877 and the ensuing institutionalization of racial segregation in the 1890s testify to the success of that campaign.

In short, the advent of black suffrage in South Carolina triggered the rise of voter suppression that shaped the state’s political landscape from the late 1860s to the present. I’ll return to this narrative in a future episode (see Episode No. 177). In the meantime, the online transcript of today’s program includes a list of suggested titles, and I encourage everyone to learn more about this unpleasant but important facet of South Carolina’s turbulent past.

Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Gillette, William. Retreat from Reconstruction, 1869–1879. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

Goldman, Robert M. Reconstruction & Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper and Row, 1988.

Jenkins, Wilbert L. Seizing the New Day: African Americans in Post-Civil War Charleston. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Powers, Bernard E. Jr. Black Charlestonians: A Social History, 1822–1885. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Powers, Bernard E. Jr. “Community Evolution and Race Relations in Reconstruction Charleston, South Carolina.” South Carolina Historical Magazine 95 (January 1994): 27–46.

Ranney, Joseph A. In the Wake of Slavery: Civil War, Civil Rights, and the Reconstruction of Southern Law. Westport, CT: Preager Press, 2006.

Rubin, Hyman III. South Carolina Scalawags. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006.

Tindall, George B. “The Campaign for the Disfranchisement of Negroes in South Carolina.” Journal of Southern History 15 (May 1949): 212–34.

Zuczek, Richard. State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

NEXT: The Myth of “Trott’s Cottage”

PREVIOUSLY: A Trashy History of Charleston’s Dumps and Incinerators

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments