Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 8

Processing Request

Processing Request

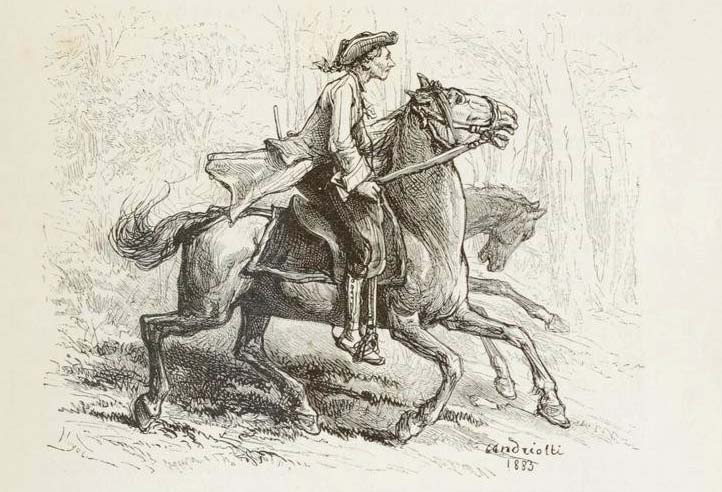

During the early months of 1760, the “Negro” man Abraham used his courage, physical endurance, and equestrian skills to blaze a path from slavery to freedom during South Carolina’s war against the Cherokee. In this conclusion of his dramatic story, we find him dressed in a new blue coat, ranging on horseback across the colonial frontier with armed troopers, and then back in Charleston in conversation with the royal governor.

In seven previous episodes, I’ve attempted to narrate the story of an enslaved man named Abraham who gained his freedom from slavery by working as an express rider during the Anglo-Cherokee War of 1760, carrying messages between the governor of South Carolina in Charleston and military outposts on the western Cherokee frontier. From his first solo trek across that distance of nearly 450 miles in late January to his ninth journey in early September, Abraham (or Abram, as he was sometimes called) performed a valuable service for the colonial government of South Carolina and earned the trust of many prominent white officials. During that period of seven months, Abraham witnessed a great deal of violence and bloodshed, camped among soldiers and civilians who were both frightened and starving, and suffered from the effects of extreme weather, injuries, and disease. Then, as abruptly as he entered the public consciousness, Abraham disappeared from the local news reports about the progress of the Cherokee War.

As I mentioned in the most recent chapter in this story (see Episode No. 110), I haven’t found any documentary evidence of Abraham’s movements during the remainder of the year 1760, so I speculated that something might have happened to him. Or perhaps he simply needed time to rest and recuperate. Abraham had worked for seven long months as one of the government’s hired, long-distance express couriers, and then he seems to have quit that work. The Charleston newspapers of late 1760 and early 1761 contain the names of several other men who performed that service, but not Abraham. He just seems to have gone off the grid.

In recent days, I’ve been reviewing my research notes compiled from countless hours of reading through the surviving records of South Carolina’s colonial government at the state archive in Columbia. Looking diligently for evidence of express riders and messages sent and received by the colony’s chief executive, I seem to have hit a dead end. I have just one very small piece of documentary evidence related to Abraham, dating from the summer of 1761. It seemed disconnected from everything that I’ve found up to this point, but I knew that it had to be important somehow. Let’s all play detective for a moment and consider the facts:

In recent days, I’ve been reviewing my research notes compiled from countless hours of reading through the surviving records of South Carolina’s colonial government at the state archive in Columbia. Looking diligently for evidence of express riders and messages sent and received by the colony’s chief executive, I seem to have hit a dead end. I have just one very small piece of documentary evidence related to Abraham, dating from the summer of 1761. It seemed disconnected from everything that I’ve found up to this point, but I knew that it had to be important somehow. Let’s all play detective for a moment and consider the facts:

On the sixth day of June, 1761, the members of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly were in the midst of a tedious, line-by-line review of recent military expenses. The House considered and approved account No. 827, a charge of £60 South Carolina currency [approximately £8 11 shillings sterling] submitted by a man named John Fairchild “for a Horse Impressed for Negro Abram 28th February 1761.”[1]

From this brief reference, we can deduce that Abraham was performing some task that required the use of a horse, and that the task in question was apparently done in the service of the provincial government (otherwise no one would ask the government for compensation). My initial interpretation of this item was an assumption—and you know what they say about making assumptions. I assumed that Abraham was commandeering a horse from John Fairchild in order to perform some mission. I assumed that Abraham was carrying express dispatches from one place to another, as he had done on nine previous occasions in 1760. The newspapers of late 1760 and early 1761 identified several other express riders who were shuttling back and forth between Charleston and Fort Prince George, but I did not find Abraham’s name among the men performing this service. In light of his absence, I brainstormed about that 1761 charge for a horse, and parsed every word until I saw the error of my ways.

Abraham did not impress or commandeer a horse from John Fairchild. Rather, John Fairchild impressed a horse for Abraham. That small attention to syntax changes the meaning entirely. So who was John Fairchild, where was he in February 1761, and what does he have to do with the story? It turns out that he is the key to what I believe is a dramatic new chapter in Abraham’s story. I don’t have many firm details at this moment, so I can only provide an outline of the events. In the coming months, however, I’ll be back in the archives looking for clues to expand the narrative. In the meantime, here’s a brief synopsis of the rest of the Cherokee War, in which we can imagine Abraham’s continued and enhanced participation.

In the late summer of 1759, Governor William Henry Lyttelton commissioned Captain John Fairchild of Charleston to raise a troop of twenty horse-mounted rangers, followed shortly by second troop raised by Captain John Hunt. From a base camp at the Congarees (modern Cayce, South Carolina), these rangers patrolled the settlements between the Saluda and Broad Rivers through the autumn and winter, bringing welcome protection to the settlers on the western frontier.[2] In February 1760, in response to the first wave of Cherokee violence on the frontier, the South Carolina legislature resolved to expand the rangers into seven troops, each consisting of seventy-five men, plus officers, totaling approximately 550 soldiers.[3] Although their numbers barely reached 350 that spring, that larger mobile force was assigned to patrol a broader area between the Congarees and Fort Prince George (under Lake Keowee now). The bulk of those rangers also accompanied the army under the command of Colonel Archibald Montgomery as they penetrated, unsuccessfully, into the Cherokee Middle Towns in the summer of 1760. In the aftermath of that military fiasco, the rank and file of South Carolina’s frontier rangers was severely depleted.

In the late summer of 1759, Governor William Henry Lyttelton commissioned Captain John Fairchild of Charleston to raise a troop of twenty horse-mounted rangers, followed shortly by second troop raised by Captain John Hunt. From a base camp at the Congarees (modern Cayce, South Carolina), these rangers patrolled the settlements between the Saluda and Broad Rivers through the autumn and winter, bringing welcome protection to the settlers on the western frontier.[2] In February 1760, in response to the first wave of Cherokee violence on the frontier, the South Carolina legislature resolved to expand the rangers into seven troops, each consisting of seventy-five men, plus officers, totaling approximately 550 soldiers.[3] Although their numbers barely reached 350 that spring, that larger mobile force was assigned to patrol a broader area between the Congarees and Fort Prince George (under Lake Keowee now). The bulk of those rangers also accompanied the army under the command of Colonel Archibald Montgomery as they penetrated, unsuccessfully, into the Cherokee Middle Towns in the summer of 1760. In the aftermath of that military fiasco, the rank and file of South Carolina’s frontier rangers was severely depleted.

On the morning of September 7th, 1760, Abraham galloped into Charleston carrying news of the massacre of the garrison of men, women, and children that had recently surrendered Fort Loudoun, in what is now eastern Tennessee, to the Cherokee Indians. This tragic and incendiary news shocked the government of South Carolina and prompted the planning of a fresh military campaign to punish the colony’s former Indian allies once and for all. In the autumn of 1760, the government commissioned officers for a new South Carolina Provincial Regiment of 1,00 foot soldiers. Major William Thompson was appointed to act as commandant of an expanded regiment of horse-mounted rangers or light-horsemen to patrol the western frontier. I believe that Abraham, a nominally-free man, was one of several men of African descent who joined Thompson’s ranger regiment and served for the remainder of the war. To supplement all of these local forces wearing blue coats, the government once again asked the British military headquarters in New York to send a large force of veteran professional soldiers in red coats.

The first wave of new rangers and infantry recruits departed Charleston in early November 1760 and headed west. While the foot soldiers established a “general rendezvous” near the Congarees, the rangers continued onward to Fort Prince George to patrol the backcountry and to recruit men to fill their ranks.[4] By December, the infantry regiment was still only half-filled, so Lt. Colonel Henry Laurens an other officers journeyed into North Carolina to recruit more men. In January of 1761, a force of 1,200 British regular troops, under the command of Colonel James Grant, sailed into Charleston harbor from New York. In the following weeks, they assembled a long train of wagons to transport a large quantity of supplies and equipment to the western frontier.

Meanwhile, the regiment of rangers had better success in filling their ranks. In early February, 1761, Major Thompson and 550 uniformed rangers departed from Fort Ninety Six (in modern Greenwood County) to escort a train of supplies up to Fort Prince George, including eighteen wagon-loads of supplies and flour and a large herd of cattle and hogs. After delivering the supplies and assisting the garrison get firewood into the fort, Thompson and his men headed back towards Ninety-Six on February 21st. That evening, as the rangers were camped under the stars at Six-Mile Creek, a party of Cherokee Indians silently infiltrated their camp and stole 129 of their horses. Some of the men were obliged to walk the rest of the way back to Fort Ninety Six, where they arrived on February 25th.[5]

On February 28th, ranger captain John Fairchild “impressed” or commandeered a horse for the use of a “Negro” known as Abram. I strongly suspect that this man was our protagonist, Abraham, who was now a uniformed soldier in the pay of the South Carolina military establishment, and whose horse had been kidnapped by the Cherokee a few days earlier.

Throughout the spring of 1761, these assembled troops trained, accumulated provisions and equipment, and slowly inched their way towards the western frontier. Finally, in June and July of that year, Colonel Grant led the combined force of more than 2,600 men into the Cherokee Lower Towns, through the dangerous Etchoé Pass (in western North Carolina), and burned fifteen of the Cherokee Middle Towns that had resisted the Anglo-colonial forces so fiercely the previous summer. The victorious troops then returned to Fort Prince George to wait for peace negotiations. Cherokee delegates signed a preliminary peace treaty in Charleston on September 22nd, 1761, and the war-weary troops began their slow march back to the coast in mid-October. By Christmas, the visiting British troops had all sailed away, South Carolina’s provincial regiment had been disbanded, and most of the backcountry rangers were discharged.[6] For all practical purposes, the war was over. In late July of 1762, the governor discharged the last of the South Carolina rangers employed during the Cherokee crisis.[7]

Confirming Abraham’s Freedom:

We cannot conclude the saga of Abraham the Unstoppable without circling back to the question of his freedom. Back in late January, 1760, Capt. Paul Demeré, the commander of Fort Loudoun, promised to secure Abraham’s manumission from slavery if he could navigate through Cherokee territory and deliver a message to the governor in Charleston (see Episode No. 101). Having accomplished that goal in mid-February, Abraham waited for several months—until mid-July—before Lieutenant Governor William Bull finally recommended Abraham’s case to the consideration of the 22nd Royal Assembly of South Carolina (see Episode No. 104). The speaker of Commons House appointed a committee to consider the matter, but the term of the 22nd Royal Assembly expired before that committee reported back to the House. Following local elections throughout the province, the 23rd Royal Assembly convened in Charleston in October of 1760. It accomplished little business in the final months of that year, however, and dissolved in late January 1761 when news of the death of King George II (on 25 October 1760) trickled into Charleston. King George III was proclaimed in an elaborate public ceremony in Charleston on February 2nd, 1761, at which time Lieutenant Governor William Bull called for fresh elections across South Carolina.[8]

We cannot conclude the saga of Abraham the Unstoppable without circling back to the question of his freedom. Back in late January, 1760, Capt. Paul Demeré, the commander of Fort Loudoun, promised to secure Abraham’s manumission from slavery if he could navigate through Cherokee territory and deliver a message to the governor in Charleston (see Episode No. 101). Having accomplished that goal in mid-February, Abraham waited for several months—until mid-July—before Lieutenant Governor William Bull finally recommended Abraham’s case to the consideration of the 22nd Royal Assembly of South Carolina (see Episode No. 104). The speaker of Commons House appointed a committee to consider the matter, but the term of the 22nd Royal Assembly expired before that committee reported back to the House. Following local elections throughout the province, the 23rd Royal Assembly convened in Charleston in October of 1760. It accomplished little business in the final months of that year, however, and dissolved in late January 1761 when news of the death of King George II (on 25 October 1760) trickled into Charleston. King George III was proclaimed in an elaborate public ceremony in Charleston on February 2nd, 1761, at which time Lieutenant Governor William Bull called for fresh elections across South Carolina.[8]

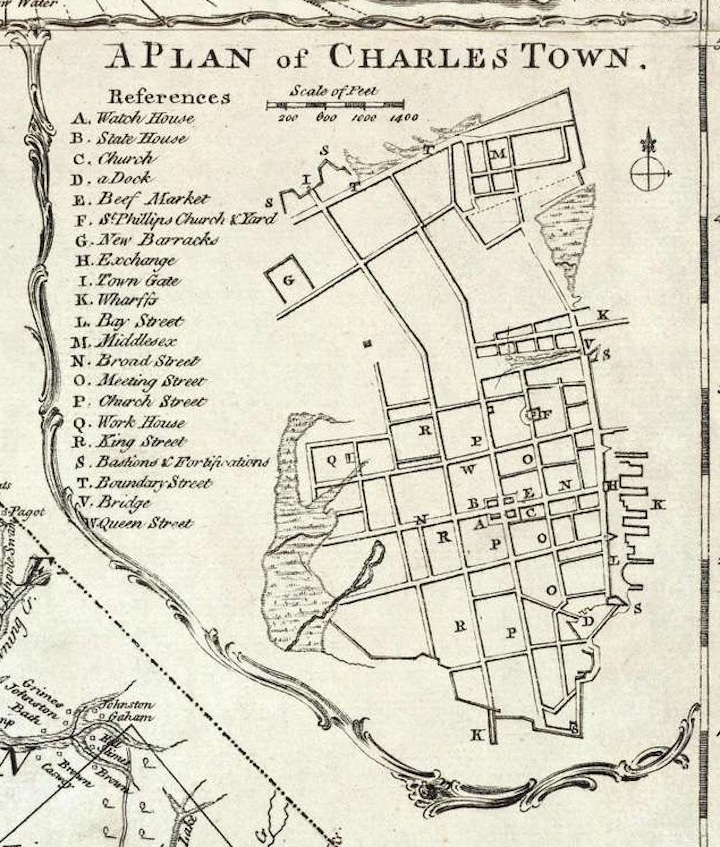

The 24th Royal Assembly convened at the State House, at the northwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets in Charleston, in late March 1761 and immediately focused its attention on the ongoing war against the Cherokee Nation. One month later, on April 22nd, an unidentified member of the Commons House made a motion “that a committee be appointed to take into consideration the Lieutenant Governor’s message to the late House dated the 12th day of June 1760 relating to the freedom of a Negro, Abram [Abraham] who had been serviceable in the Cherokee Country.” The motion was seconded and carried, and the Speaker of the House, Benjamin Smith, appointed a committee consisting of Charles Pinckney (1732–1782), George Logan, Peter Manigault, Rawlins Lowndes, and John Savage to consider the matter. The following day, April 23rd, representative Charles Pinckney stood before his colleagues in the Commons House chamber and read aloud the following report:

“That on consideration of the singular services done by the said Negro to this province in carrying expresses to & from Charles Town to the garrisons of Fort Loudoun & Fort Prince George in the Cherokee Country amidst a variety of dangers & difficultys [sic,] the said Negro ought to be made free, and therefore [we] do recommend that the sum of five hundred pounds current money [of South Carolina, worth approximately £71 sterling] be provided in the schedule to be annexed to the next Tax Bill as a consideration for the purchase of the said Negro’s freedom to be paid to his master. This encouragement the committee are of opinion will excite other Negro slaves on proper occasions to undertake the like dangerous & necessary services for the province in hopes of meeting with the like reward & that therefore the same ought chearfully [sic] to be complied with.”[9]

A week later, on April 30th, 1761, the Commons House considered and debated “the report of the committee on the Lieutenant Governor’s message with respect to the Negro Abram.” After a brief discussion, which was not recorded, the members of the House “resolved that the sum of five hundred pounds be provided in the schedule to be annexed to the next Tax Bill as a consideration for the purchase of the freedom of the said Negro slave Abram.” Two months later, on June 23rd, a rough draft of South Carolina’s annual tax bill included a line-item charge of £500 “for purchasing the freedom of a Negro named Abraham.”[10] The funds appropriated for this purpose were included under the heading of “Extraordinary Charges” in the final draft of the tax bill to fund government expenses incurred during the year 1760, which the South Carolina General Assembly formally ratified on July 30th, 1761.[11] The provincial treasurer then cut a check, so to speak, to compensate Abraham’s legal owner, and the “Negro express,” as he was once called, officially became a free man.

Interpreting for the Governor:

I haven’t yet found any sort of paper trail to shed light on Abraham’s movements in the latter part of 1761 and beyond. As a free man of African descent who had once lived on the Cherokee frontier, Abraham’s recent employment had enabled him to become acquainted with people of considerable influence in Charleston and other places in the interior of South Carolina. He had, undoubtedly, developed some measure of reputation as a strong, brave, and trustworthy man, and could have settled in any number of places within the colony, or perhaps beyond. Finding biographical details about such a person who lived on the margins of that Anglo-dominated society some two hundred and fifty years ago is very difficult today. Nevertheless, I’ve found one small piece of evidence that places him in Charleston in the spring of 1762, in conversation with the new governor of South Carolina.

Thomas Boone (1730–1812), newly-appointed Royal governor of South Carolina, arrived in Charleston from New York on December 22nd, 1761. Boone was a wealthy young Englishman who had inherited “a very large estate” in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, and was residing here in early 1760 when he learned that he had been appointed governor of New Jersey. He departed Charleston in April of 1760 to take up residence in that northern colony, but then was ordered to return in late 1761 to serve as governor of South Carolina.[12] His predecessor, Lt. Governor William Bull, had concluded a peace treaty with the Cherokee Indians a few months before Boone arrived, but the larger war against France and its Indian allies continued. In mid-May, 1762, Governor Boone learned that Britain had also declared war on Spain, and he was required to formally proclaim this new branch of the war in Charleston.[13]

Around that same time (the precise date was not recorded), the governor learned that a small party of Chickasaw Indians—four warriors of the distant “Upper Nation,” one woman, and “two or three children”—had arrived in Charleston without an interpreter. A messenger told Governor Boone that no one in Charleston could understand why these Chickasaw had come to town, but it appeared one of the natives spoke Cherokee. Upon hearing this fact, Boone “ordered them to attend” him in his chambers at the State House, and sent his messenger to summon “the negro man Abraham who spoke and understood the Cherokee language, in order that they [the Chickasaw] might have an opportunity of communicating their intention of coming hither.”

When the natives and Abraham arrived at the State House, Governor Boone invited the small band into his chambers, shook their hands, and said that he “was glad to seem them.” Communicating through the free black interpreter, the governor explained “that he would have seen them sooner if he could have procured an Interpreter” who spoke Chickasaw, but none were available in town. Abraham informed the visitors that the white governor “desired to know if any more of their people were coming [to Charleston] on this occasion.” The Chickasaw replied, in Cherokee, to Abraham, that they knew of no other Chickasaw coming to town; that they had come to the metropolis of South Carolina simply out of curiosity, and desired to see the white governor about whom they had heard stories. After just a few minutes of this polite, three-way conversation, Governor Boone instructed Abraham to tell his guests that he would send orders to the Commissary General of the province, William Pinckney, “to take proper care of them and to furnish them plentifully with provisions” during their visit to Charleston. With that hospitable gesture, the colorful band of visitors made their salutations and departed in peace.[14]

That’s A Wrap for Abraham:

After that conversation with Governor Thomas Boone in late May, 1762, the name of our protagonist, Abraham, vanishes from the record books of colonial South Carolina. The disappearance of his paper trail is certainly unfortunate, but it’s not unusual. It’s difficult to reconstruct a robust biography of anybody who lived during this formative era of South Carolina’s history, and it’s nearly impossible to find biographical details about people who weren’t part of the socio-economic elite. Back in early February of this year (see Episode No. 99), I mentioned that I believe it’s important to take hold of the minute threads of details about people like Abraham and to make an effort to pull them closer to the foreground. By viewing a broad, important episode in our history like the Anglo-Cherokee War through the experiences of an enslaved man caught in the middle of the action, for example, we gain a valuable new perspective on South Carolina’s past. Abraham wasn’t a principal character in that turbulent scene, but learning about his actions, his struggles, his choices, and his triumphs over adversity helps us to appreciate the diversity of experiences that shaped our community in the distant past.

After that conversation with Governor Thomas Boone in late May, 1762, the name of our protagonist, Abraham, vanishes from the record books of colonial South Carolina. The disappearance of his paper trail is certainly unfortunate, but it’s not unusual. It’s difficult to reconstruct a robust biography of anybody who lived during this formative era of South Carolina’s history, and it’s nearly impossible to find biographical details about people who weren’t part of the socio-economic elite. Back in early February of this year (see Episode No. 99), I mentioned that I believe it’s important to take hold of the minute threads of details about people like Abraham and to make an effort to pull them closer to the foreground. By viewing a broad, important episode in our history like the Anglo-Cherokee War through the experiences of an enslaved man caught in the middle of the action, for example, we gain a valuable new perspective on South Carolina’s past. Abraham wasn’t a principal character in that turbulent scene, but learning about his actions, his struggles, his choices, and his triumphs over adversity helps us to appreciate the diversity of experiences that shaped our community in the distant past.

In these eight episodes about “Abraham the Unstoppable,” I’ve tried to weave a handful of disconnected documentary crumbs about an obscure character into the fabric of a compelling biographical narrative. I’ll be the first to admit that my effort contains many rough edges and shortcomings, but I hope you’ll join me in thinking that it was worth the effort. This project was really a sort of experiment for me, and I’ve learned a lot along the way. There are many more fascinating stories like this to be found in our local archives, just waiting for the creative attention of researchers like you and me. In the coming months, I’m going to dive back into to the amazing records at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia and search for more crumbs of Abraham’s life. After that, I hope to revise all of this material and compile it into a proper book. In the meantime, I hope you’ve enjoyed this serial story of Abraham, one of South Carolina’s many forgotten black heroes, whose dramatic story certainly deserves to be remembered.

[1] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 34 (1761), page 140.

[2] Terry Lipscomb, ed. The Colonial Records of South Carolina: The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, October 6, 1757–January 24, 1761 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1996), 436 (8 October 1759) (available online through SCDAH).

[3] The legislative decision to expand the rangers is mentioned in South Carolina Gazette, 9–16 February 1760.

[4] See South Carolina Gazette, issues of 20–27 September, and 18–25 October 1760.

[5] South Carolina Gazette, 28 February–7 March 1761.

[6] Fitzhugh McMaster, Soldiers and Uniforms: South Carolina Military Affairs, 1670–1775 (Columbia: South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, 1971), 62–65.

[7] Governor Boone published a notice discharging the remaining rangers on 20 July in South Carolina Gazette, 10–17 July 1762.

[8] South Carolina Gazette, 31 January–7 February 1761.

[9] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 34 (1761), pages 44, 49.

[10] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, No. 34 (1761), pages 57, 183.

[11] The title of “An Act for raising and granting to his Majesty the sum of two hundred and eighty-four thousand seven hundred and fifty seven pounds seventeen shillings and four pence three farthings, and applying twenty-four thousand and seventy pounds nineteenth shillings and eight pence three farthings, being surplus of taxes and the balance of several funds in the Public Treasury, making together, three hundred and eight thousand eight hundred and twenty-eight pounds seventeen shillings and one penny half-penny, to defray the charges of this government from the first day of January to the thirty-first day of December, one thousand seven hundred and sixty, both days inclusive, and for other services therein mentioned,” is given in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 4 (Columbia: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 155, but the editor of that work omitted the text of the act. The full text can be found among the engrossed manuscript acts of the South Carolina General Assembly at SCDAH.

[12] See the local news in the South Carolina Gazette, issues of 9–16 February 1760, 3–10 May 1760, and 19–26 December 1761.

[13] South Carolina Gazette, 15–22 May 1762.

[14] SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, January 1761–December 1762 (Sainsbury’s transcription), pages 506–7 (29 May 1762). Boone informed the Council that this event had occurred “lately.”

PREVIOUS: The Decline of Charleston’s Streetcars

NEXT: The historic landscape of the Wando Mount Pleasant Library

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments