Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 3

Processing Request

Processing Request

Today we continue our narrative of the enslaved man Abraham by following his perilous solo trek from the Cherokee mountains of eastern Tennessee to the coastal port of Charleston, with a few pit stops along the way. Promised freedom if he could complete this dangerous mission, Abraham found a provisional reward extended by the governor, and a crowded town wracked by fear and disease in the spring of 1760.

When we last saw our hero, Abraham, he was trapped inside Fort Loudoun (in modern Monroe County in eastern Tennessee) along with a garrison of nearly two hundred Anglo-American soldiers and some of their families. Cherokee warriors from the Overhill Towns had embarked on a campaign of violence to murder and terrify the white traders living among them, and to prevent communication and supplies from reaching the fort. Captain Paul Demeré, the commanding officer at Fort Loudoun, had promised to secure Abraham’s freedom from slavery if he could deliver official messages to the South Carolina governor, William Henry Lyttelton (1724–1808), in Charleston. Indians lurking outside the fort had already silenced two messengers attempting to leave the fort, and now Abraham was about to make a third attempt. On the 26th of January, 1760, he quietly slipped out of the fort’s gate and headed southeastward for Fort Prince George (which is now under Lake Keowee in modern Pickens County, South Carolina).

In traversing the distance between the two forts, Abraham was obliged to pass through the entire breadth of the Cherokee country, from the Overhill Towns in what is now eastern Tennessee, through the Middle Towns in western North Carolina, across the northeast corner of modern Georgia, and through the Lower Towns in western South Carolina. The “common route” between the two forts was a rambling path of 165 miles, leading from one Cherokee town to the next and crossing numerous bold creeks and narrow valleys. Considering the fact that many of the Cherokee were determined to make war against the colonial presence at that moment, Abraham probably avoided the “common route” and sought a path less traveled. The alternate route was shorter, only 130.5 miles, but it traversed the much more rugged terrain over and through the “Four and Twenty Mountains” that now form part of the Nantahala National Forest. During the frozen late January of 1760, Abraham trekked on his own through the inhospitable wilderness for eight days and seven nights, averaging about eighteen miles a day, and arrived at Fort Prince George on Saturday, February 2nd.[1]

In early February 1760, the garrison at Fort Prince George consisted of Lieutenant Richard Coytmore and a detachment of soldiers drawn from His Majesty's Independent Companies and the South Carolina Provincial Regiment. In addition to the soldiers, several white traders who lived among the Cherokee Lower Towns had also fled to the safety of the fort as violence spread across the region that January. The fort was supplied with “a pretty good stock of provisions and ammunition,” thanks to the recent visit of Governor William Henry Lyttelton and more than one thousand South Carolina militiamen, but its supply of firewood was nearly exhausted. Cherokee snipers in the hills surrounding Fort Prince George discouraged the men from foraging for firewood during daylight hours, and hundreds of armed Indians surrounded the fort more closely each night from sunset to sunrise. Fetching water from a nearby stream was also too dangerous, so the men had begun digging a well within the fort’s red clay soil. Since the governor’s hasty departure five weeks earlier, however, the dreaded smallpox had also appeared within the fort. Many of the men were now gravely ill, and little work could be done. Despite these perilous conditions, Lieutenant Coytmore wrote to his superiors in Charleston that he and his men were prepared to “defend Fort Prince-George to the last extremity.”[2]

In early February 1760, the garrison at Fort Prince George consisted of Lieutenant Richard Coytmore and a detachment of soldiers drawn from His Majesty's Independent Companies and the South Carolina Provincial Regiment. In addition to the soldiers, several white traders who lived among the Cherokee Lower Towns had also fled to the safety of the fort as violence spread across the region that January. The fort was supplied with “a pretty good stock of provisions and ammunition,” thanks to the recent visit of Governor William Henry Lyttelton and more than one thousand South Carolina militiamen, but its supply of firewood was nearly exhausted. Cherokee snipers in the hills surrounding Fort Prince George discouraged the men from foraging for firewood during daylight hours, and hundreds of armed Indians surrounded the fort more closely each night from sunset to sunrise. Fetching water from a nearby stream was also too dangerous, so the men had begun digging a well within the fort’s red clay soil. Since the governor’s hasty departure five weeks earlier, however, the dreaded smallpox had also appeared within the fort. Many of the men were now gravely ill, and little work could be done. Despite these perilous conditions, Lieutenant Coytmore wrote to his superiors in Charleston that he and his men were prepared to “defend Fort Prince-George to the last extremity.”[2]

Abraham lingered a few days at Fort Prince George—perhaps resting from his long trek through the mountains, and perhaps awaiting the best opportunity to sneak out undetected. The terrain of his path from the fort to Charleston was far less treacherous, and a horse would greatly expedite the next leg of the journey. Contemporary accounts suggest that the men at Fort Prince George kept their horses in a pasture beyond the fort’s wooden walls, however, and the surrounding Cherokee had effectively cut off access to the soldiers’ best mode of transportation. Undeterred by this Indian embargo, Abraham snuck out of the fort on the evening of February 6th and crept a short distance up the path to the nearby Cherokee town of Keowee, the capital of the Lower Towns. The dark-skinned man moved stealthily through the scores of domestic huts, gathering intelligence about the strength of the neighboring Indians. Finding a horse “that was tyed [sic] under a corn house in the middle of town,” Abraham slipped onto the animal’s back and stole back to the safety of Fort Prince George. The next day, February 7th, Lieutenant Coytmore handed Abraham a packet of letters for Governor Lyttelton and bid him a safe journey as he galloped through the fort’s gate on his way to Charleston.[3]

Abraham’s next stop, a day or so later, was the fortified outpost called Ninety Six, now a National Historic Site in Greenwood County, South Carolina, located about eighty miles southeast of Fort Prince George. There he learned about recent bloodshed in the frontier region he had just traversed. Hundreds of white colonists in the nearby Long Cane settlement, in modern McCormick County, were terrified by the Cherokee’s recent acts of aggression and decided to evacuate to the safety of Fort Augusta on the Savannah River. On the first day of February, about one hundred Cherokee warriors on horseback attacked a wagon train carrying nearly 200 settlers from the Long Cane area. After killing and scalping dozens of men, women, and children, the Indians carried away many of the survivors as slaves to be traded among the Cherokee towns.[4] Two days later, on February 3rd, a group of approximately forty Cherokee warriors launched a brief attack on the small wooden fort at Ninety Six. The fort's garrison, under the command of Captain Thomas Bell, consisted of just “33 resolute white men, and 12 stout Negroes, all armed.” During that battle, Abraham’s legal owner, the white Indian trader Samuel Benn, was “slightly wounded in the head,” and the outpost was still keeping up a vigilant guard when Abraham arrived on horseback a few days later.[5]

We have no record of Abraham’s reunion with Samuel Benn at Fort Ninety Six, but the two men surely must have had a serious conversation about the enslaved man’s future. At that moment, Abraham was on an official mission carrying important messages to the governor in Charleston, but technically he was still the chattel property of a private citizen. Captain Paul Demeré had promised Abraham freedom in exchange for completing the mission, but the captain had not consulted Sam Benn about the matter, as the two men were more than two hundred miles apart at the time. If he wished, Benn could have scuttled the plan by detaining Abraham at Fort Ninety Six and sending another express rider in his stead to Charleston. But Sam Benn did not detain Abraham, and he did not attempt to thwart the enslaved man’s journey towards freedom. Perhaps he recognized that Abraham had already completed an extraordinarily difficult journey across the mountains and through hostile territory, and chose not to prevent him from gaining the promised reward at the end of his mission. Perhaps he recognized Capt. Demeré’s offer to Abraham as a gentleman’s bond—a pact that Benn would be most impolite to break. Perhaps we can even imagine that Sam Benn might have felt a bit of pride in Abraham’s accomplishment. The two men had spent several years together as master and slave, riding the long and lonely trail between Tanasi and Charleston. Now Abraham was risking his life to assist both the white settlers and the colony in general, and to gain his freedom from slavery.

All speculation aside, we know for certain that Abraham told the white defenders inside Fort Ninety Six about Captain Demeré’s promise of emancipation, and we know that someone within the fort asked Samuel Benn how he felt about that transaction. A later newspaper report captured the Indian trader’s reaction. Benn said “he has no objection to his [Abraham’s] being made free, but[,] as he has lost his all, except this negro, in the present troubles, [he] hopes the province will not let him be a sufferer.”[6] In other words, Sam Benn didn’t object to Abraham’s manumission from slavery, so long as the provincial government of South Carolina offered him a reasonable compensation. The Indian war had destroyed his livelihood of more than twenty years, his property, and perhaps his family in Tanasi. Abraham represented a serious investment of Benn’s time and money, and that equity was all that remained with which he could begin anew. Despite his losses, Benn didn’t resent Abraham’s opportunity to gain his freedom, as long as it didn’t empty his pockets completely.

All speculation aside, we know for certain that Abraham told the white defenders inside Fort Ninety Six about Captain Demeré’s promise of emancipation, and we know that someone within the fort asked Samuel Benn how he felt about that transaction. A later newspaper report captured the Indian trader’s reaction. Benn said “he has no objection to his [Abraham’s] being made free, but[,] as he has lost his all, except this negro, in the present troubles, [he] hopes the province will not let him be a sufferer.”[6] In other words, Sam Benn didn’t object to Abraham’s manumission from slavery, so long as the provincial government of South Carolina offered him a reasonable compensation. The Indian war had destroyed his livelihood of more than twenty years, his property, and perhaps his family in Tanasi. Abraham represented a serious investment of Benn’s time and money, and that equity was all that remained with which he could begin anew. Despite his losses, Benn didn’t resent Abraham’s opportunity to gain his freedom, as long as it didn’t empty his pockets completely.

After resting briefly at Fort Ninety Six and collecting official dispatches for the governor, Abraham saddled his horse (the one stolen from Keowee or perhaps a fresh mount) and continued his southeastward journey to Charleston. Within a couple of hours he would have covered about twenty miles and reached the little settlement called Saluda Town (in modern Saluda County). At this small fortified outpost, Abraham probably stopped to exchange news and enjoy some refreshments. Departing from Saluda, he faced a fork in the road. On the one hand, he could have continued due east approximately forty-three miles along what is now Highway 378 to another colonial fort at a place called the Congarees, an important trading post on the west bank of the Congaree River now occupied by the town of Cayce. Alternatively, Abraham could have continued southeasterly along what is now Highway 178 about seventy-four miles to another small, fortified settlement at Beaver Creek, near the modern town of North in Orangeburg County. Published reports of Abraham’s later movements confirm that he stopped at one or the other of these sites on various journeys, but it’s not clear which route he followed during his first solo run in February of 1760.

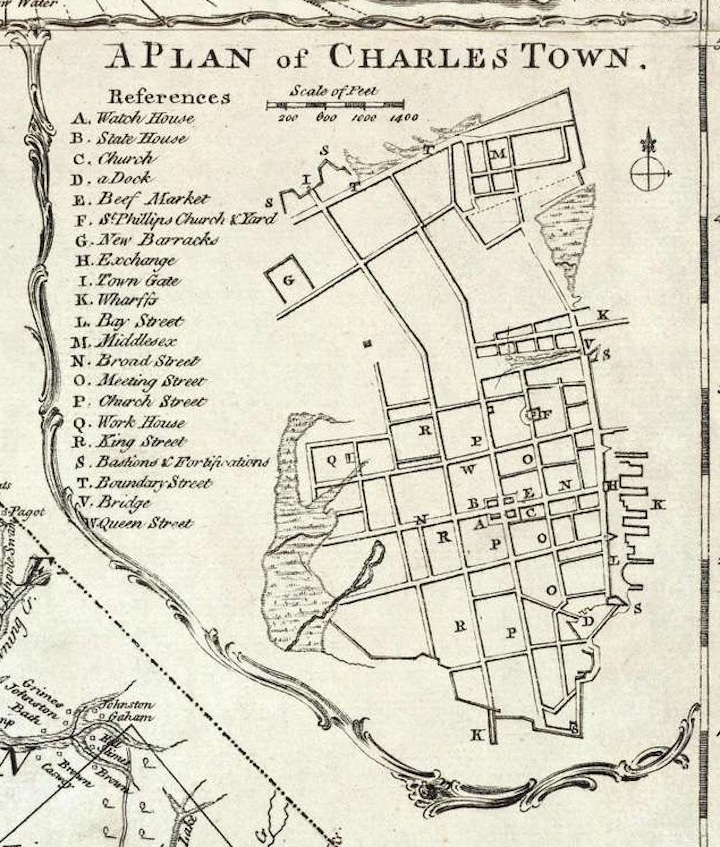

If he stopped at the Congarees, Abraham would have then continued southeastward to Moncks Corner, along a route similar to the present Highway 176. If he set out from Beaver Creek, he would have continued along a path that is now Highway 178 and 78, from Orangeburg to Dorchester. Either way, Abraham would have seen more and more white colonists and enslaved people as he traversed the flat coastal plain. Closer to his destination, both routes converged at a point marked by a tavern called the Six Mile House in what is now the city of North Charleston, at the northern boundary of the parish of St. Philip. From that point, Abraham followed the “Broad Path” that meandered down the center of the peninsula between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers.

Just north of the town boundary, the Broad Path terminated at the gate of a newly-constructed fortification that guarded the entrance to Charleston. The walls of the “Horn Work,” so called because of its two north-projecting half-bastions, stretched several hundred feet to the east and west of the road. In the center of its high curtain wall, which was constructed of oyster-shell tabby, stood a large archway that framed a heavy wooden gate. If Abraham arrived during daylight hours, he would have found the broad doors open. If he arrived after sunset, he would have found the gate closed and the post guarded by members of the town’s military night watch until sunrise. We don’t know exactly what time of day he arrived, but, let’s assume that Abraham arrived around mid-day, and was able to pass under the gate without interruption. From that point, just above what is modern Calhoun Street, the “Broad Path” officially became King Street.[7]

Just north of the town boundary, the Broad Path terminated at the gate of a newly-constructed fortification that guarded the entrance to Charleston. The walls of the “Horn Work,” so called because of its two north-projecting half-bastions, stretched several hundred feet to the east and west of the road. In the center of its high curtain wall, which was constructed of oyster-shell tabby, stood a large archway that framed a heavy wooden gate. If Abraham arrived during daylight hours, he would have found the broad doors open. If he arrived after sunset, he would have found the gate closed and the post guarded by members of the town’s military night watch until sunrise. We don’t know exactly what time of day he arrived, but, let’s assume that Abraham arrived around mid-day, and was able to pass under the gate without interruption. From that point, just above what is modern Calhoun Street, the “Broad Path” officially became King Street.[7]

Nineteen days after passing through the snow-covered gate of Fort Loudoun, and seven days after leaving Fort Prince George, Abraham rode into Charleston at a “moderate trot” (the urban speed limit at the time) on Wednesday, February 13th.[8] According to the local weather report, it was a mild, cloudy day in the capital of South Carolina, with a morning low of 60 degrees Fahrenheit and an afternoon high of 71.[9] The unpaved, sandy streets would have been filled with pedestrians and horse-drawn carts as people went about their daily business. Of the approximately 10,000 people living within the peninsular city’s fortified boundaries, roughly half were enslaved Africans and creole people born into a life of slavery in the colony. Abraham, no doubt dressed in the weathered garb of a backwoodsman, would have stood out among the brightly-attired townsfolk, but Charleston of that era was also community of diverse peoples, languages, and cultures. The appearance of a weary backcountry “Negro” man on horseback may have been slightly out of the ordinary, but it certainly wasn’t cause for alarm in a town filled with a motley cast of characters.

Abraham’s instructions were to deliver messages directly to Governor Lyttelton, the highest-ranking man in the colony—but how did he know where to find the man? Having worked with his master, Samuel Benn since the mid-1750s, if not longer, Abraham had likely visited Charleston numerous times as the two men drove a train of pack horses carrying trade goods between the port city and the Overhill Cherokee town of Tanasi. It’s doubtful that he ever had cause to visit the governor on any previous occasion, but Abraham probably had a decent knowledge of the town’s layout. The governor’s office was fairly easy to find; it was in a prominent public building called the Council Chamber, a two-and-a-half-story brick structure perched within a half-moon-shaped fortification at the intersection of Broad and East Bay Streets. (Today that site is occupied by the Old Exchange Building, completed in 1771.) The ground floor of the Council Chamber building served as the headquarters and holding cells of the town’s night watch, while the governor and his council of advisors occupied the more elaborate state room above. Ascending the steps to the small lobby outside the governor’s office, Abraham would have met a white clerk who asked the nature of his visit. The details of such mundane conversations are not recorded in surviving government records, but I suspect that the Clerk of Council took Abraham’s packet of letters and told the enslaved man to wait outside while he delivered the materials to the governor.[10]

The people of Charleston had not received any news from Fort Loudoun since the beginning of January, and a rumor was circulating that the garrison had been lost by a surprise attack or some stratagem of Indian deception. Bits and pieces of the story of the massacre at Long Canes had trickled down to the Lowcountry in the days before Abraham’s arrival, however, and Governor Lyttelton had already sounded the call for reinforcements. On February 7th, Lyttelton informed the Commons House of Assembly, which had just convened at the new State House at the northwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, that he had received tragic news from the frontier. The Cherokee had “lately massacred a considerable number of his Majesty’s subjects, trading in their towns, and slain divers inhabitants of the settled parts of this province which they now actually infest with their incursions. . . . in consequence whereof I have apply’d to his Excellency Major General [Jeffrey] Amherst [the British commander in North America], for a body of His Majesty’s Troops to be sent hither, and am ready to concert with you such other measures as may be most advantageous for His Majesty’s Service, and the safety and welfare of this province.”[11]

On February 13th, Governor Lyttleton no doubt anxiously opened and read the letters delivered by Abraham. In them, he learned the Cherokee had effectively trapped the garrisons at Fort Loudoun and Fort Prince George, as well as the nearby traders and settlers, within those palisaded walls. Both forts had sufficient food provisions for the moment, but the fetching of fresh water and firewood were now dangerous tasks. Smallpox was ravaging their effective strength. Scores of settlers on the western frontier had been murdered and kidnapped by roving bands of Cherokee warriors, and the Indians had even attacked the small fort at Ninety Six. The South Carolina backcountry was in a dismal situation, and in desperate need of assistance from the Lowcountry and beyond.

On February 13th, Governor Lyttleton no doubt anxiously opened and read the letters delivered by Abraham. In them, he learned the Cherokee had effectively trapped the garrisons at Fort Loudoun and Fort Prince George, as well as the nearby traders and settlers, within those palisaded walls. Both forts had sufficient food provisions for the moment, but the fetching of fresh water and firewood were now dangerous tasks. Smallpox was ravaging their effective strength. Scores of settlers on the western frontier had been murdered and kidnapped by roving bands of Cherokee warriors, and the Indians had even attacked the small fort at Ninety Six. The South Carolina backcountry was in a dismal situation, and in desperate need of assistance from the Lowcountry and beyond.

The letters from the commanders of the frontier forts provided valuable intelligence, but they also raised new questions. I think it’s likely that Governor Lyttelton would have called Abraham into his chambers for a face-to-face interview, perhaps with an audience consisting of the governor’s privy council. The enslaved man had personally lived among the Cherokee for some time, and had recently witnessed the conditions at each of South Carolina’s fortified outposts. Surely he could provide some insight into the recent atrocities that had prompted his dangerous journey of more than four hundred miles to Charleston. And then, of course, there was the question of Captain Demeré’s promise to Abraham, of which the captain informed the governor in his letter of January 26th.

“Capt. Demeré writes of an offer he made to you,” Lyttelton might have said, “promising your freedom if you could deliver these messages to Charleston.” Abraham, hat in hand, no doubt nodded respectfully in response to this momentous question. We could certainly invent some dialog based on the scenario, but I’ll resist the temptation for the moment. Although there is no record of their conversation about this matter, it certainly merited some executive discussion. Abraham was not the first enslaved man to have been offered freedom in exchange for service to the government, nor would he be the last. By 1760, South Carolina’s provincial legislature had a well-established legal protocol for dealing with such cases, dating back to the year 1703.[12] I’m confident that one of Governor Lyttelton’s Royal Councilors would have informed him of such details. The process worked like this: one party (either the enslaved man, his owner, or an agent on their behalf) submitted a petition in writing to the Commons House of Assembly, describing the circumstances that merited the slave’s manumission. The members of House listened to their clerk read the petition aloud and then debated whether or not to consider the matter set before them. If they approved the petitioner’s request, the speaker of the House would appoint a committee of several men to verify the truth of the circumstances described in the petition, and then to determine the market value of the enslaved man in question. If the committee found that the enslaved man had indeed performed some extraordinary service to the government, and the Commons House approved of the price recommend by the committee, the speaker would order the public treasurer to pay the agreed sum to the legal owner of the slave. By this act of government purchase, the enslaved man was set free, and the slave owner received compensation for his loss of property.

But we’re jumping ahead in the story. On February 13th, the day Abraham completed his mission by delivering a packet of letters to the governor, the legislative protocol leading to his manumission had yet to begin. Governor Lyttelton might very well have said something congratulatory, like “Well, Abram, it appears that you have rightly earned the reward promised you by Captain Demeré,” but the legal steps required to confirm his manumission would have to come later. At that moment, however, circumstantial evidence suggests that the governor (with the advice and consent of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina) informally honored Captain Demeré’s promise with immediate effect. In other words, they thanked Abraham for his fidelity and service in the face of great danger, and informed him that he would henceforth be considered a free man while the legislature attended to the technicalities. This unofficial, de facto manumission was later mentioned in the local newspaper, but it would not be honored in Charleston unless the story of Abraham’s recent deeds circulated through the town immediately. And that’s exactly what happened next.

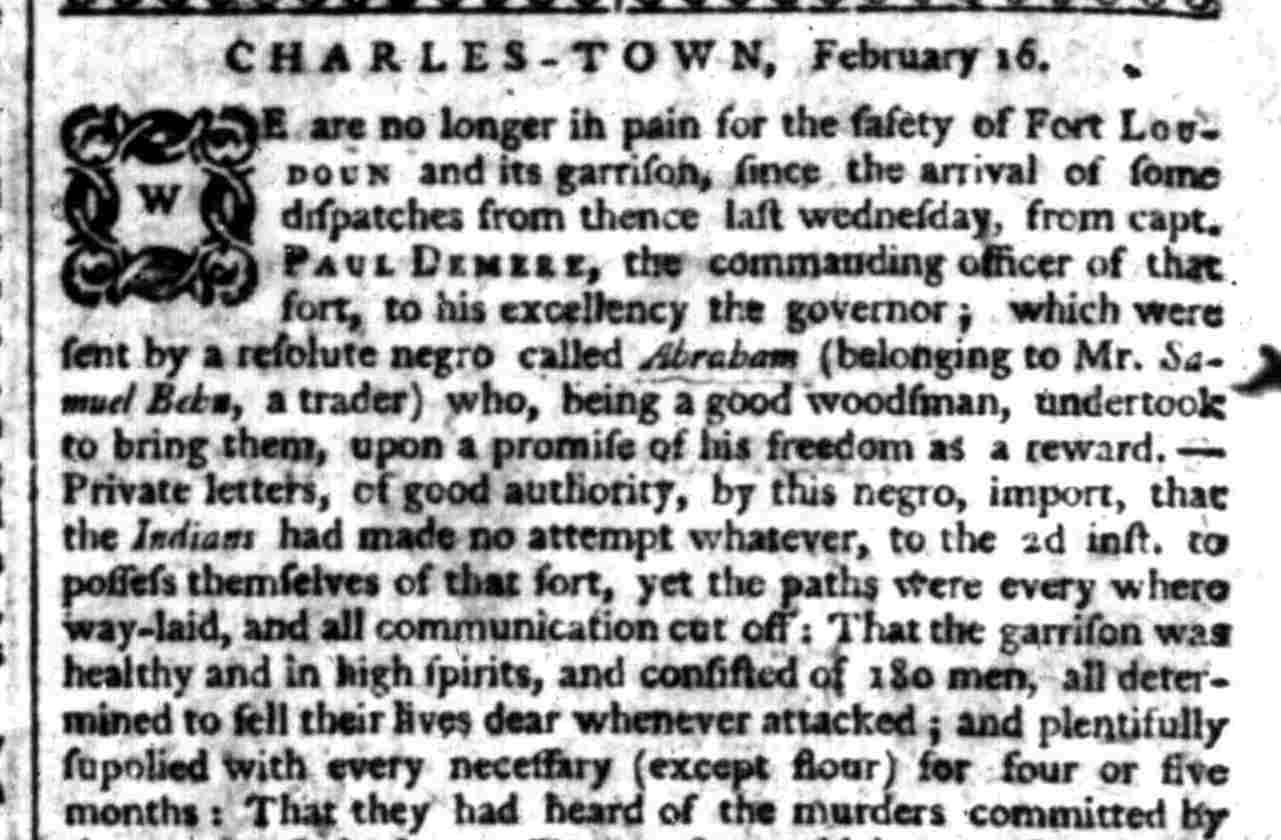

On the morning of Saturday, February 16th, 1760, the workshop of Peter Timothy printed his regular weekly edition of the South Carolina Gazette, containing the latest intelligence from parts near and far. The very first item of local news, printed on the second of the paper’s four pages, mentioned Abraham’s recent accomplishment:

“We are no longer in pain for the safety of Fort Loudoun and its garrison, since the arrival of some dispatches from thence last Wednesday [13 February], from Capt. Paul Demeré, the commanding officer of that fort, to his Excellency the Governor; which were sent by a resolute negro named Abraham (belonging to Mr. Samuel Behn, a trader) who, being a good woodsman, undertook to bring them, upon a promise of his freedom as a reward. Private letters, of good authority, [brought] by this Negro, import, that the Indians had made no attempt whatever, to the second inst. [February 2nd], to possess themselves of that fort, yet the paths were every where way-laid, and all communication cut off: That the garrison was healthy and in high spirits, and consisted of 180 men, all determined to sell their lives dear whenever attacked. . . . The last accounts from Lieut. Coytmore, are of the 7th instant, by the same express [that is, Abraham] which brought the above intelligence: They import, that the Cherokees still continued to beset Fort Prince-George; that the hills about and in sight of it were full of Indians; that it was almost impracticable to give or receive intelligence. . . .”[13]

“We are no longer in pain for the safety of Fort Loudoun and its garrison, since the arrival of some dispatches from thence last Wednesday [13 February], from Capt. Paul Demeré, the commanding officer of that fort, to his Excellency the Governor; which were sent by a resolute negro named Abraham (belonging to Mr. Samuel Behn, a trader) who, being a good woodsman, undertook to bring them, upon a promise of his freedom as a reward. Private letters, of good authority, [brought] by this Negro, import, that the Indians had made no attempt whatever, to the second inst. [February 2nd], to possess themselves of that fort, yet the paths were every where way-laid, and all communication cut off: That the garrison was healthy and in high spirits, and consisted of 180 men, all determined to sell their lives dear whenever attacked. . . . The last accounts from Lieut. Coytmore, are of the 7th instant, by the same express [that is, Abraham] which brought the above intelligence: They import, that the Cherokees still continued to beset Fort Prince-George; that the hills about and in sight of it were full of Indians; that it was almost impracticable to give or receive intelligence. . . .”[13]

By the end of the day, nearly everyone in Charleston had heard about Abraham’s recent express mission from Fort Loudoun to Charleston. There were other men paid to carry express messages along similar routes between government officials in far-flung locations, but Abraham had undertaken and completed a dangerous journey in order to gain his freedom. His mere presence in Charleston was proof that he had fulfilled his task and had earned his reward.

As a newly-freed man standing within a city crowded with the trappings of slavery, what would Abraham do next? Would he return to the backcountry, and seek out his now-former owner, Samuel Benn? Would he return to Fort Loudoun to thank Capt. Demeré? Or would he remain in Charleston and begin a new life of his own. We have no record of Abraham’s dreams or plans from this moment, but surviving documents do confirm one very important fact about our hero’s first taste of freedom: he had a blistering fever.

Having trekked across the frozen mountains of Nantahala, crossed numerous icy rivers and creek, galloped across the breadth of South Carolina, and camped with men infected with the smallpox, Abraham was no doubt exhausted and weakened. Now a free man, he discovered that the dreaded and deadly pox had accompanied him to Charleston. In fact, the virus had come to town weeks before his arrival, with the return of Governor Lyttelton’s expedition from Fort Prince George in early January. Of the 10,000 people in that town in the spring of 1760, one in fourteen died of the pox, and the town was in a veritable state of panic. Free, alone, and now covered in tiny, puss-filled blisters, Abraham was laid low and incapacitated. Our hero now entered a dark time, but fear not for his safety and survival. After all, he was Abraham the resolute “Negro” man, Abraham the indomitable, Abraham the unstoppable, and his story continues!

[1] These two routes are described in detail in a column of the South Carolina Gazette, 28 June–5 July 1760 (see illustration on this page). Daniel J. Tortora, Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 96, says the distance between Fort Loudon and Fort Prince George was 150 miles, and that Abraham made this journey in “just over a week.” The brief description of Abraham’s journey in South Carolina Gazette, 9–16 February 1760, suggests that he arrived at the latter fort on 2 February.

[2] South Carolina Gazette, issues of 2–9 February and 9–16 February 1760.

[3] Tortora, Carolina in Crisis, 98, citing a letter from Lieutenant Coytmore to Governor Lyttelton (which letter Abraham personally delivered).

[4] Tortora, Carolina in Crisis, 105. This incident is described in South Carolina Gazette, 2–9 February 1760 (which says about 150 people were attacked), and in South Carolina Gazette, 16–23 February 1760 (which says about 250 people were attacked). The massacre took place near the modern town of Troy in McCormick County, South Carolina. See http://www.nationalregister.sc.gov/mccormick/S10817733008/index.htm.

[5] See South Carolina Gazette, issues of 2–9 February and 9–16 February 1760. In a separate incident on March 3rd, published in South Carolina Gazette, 8–15 March 1760, “about 240 or 250 Indians” attacked Fort Ninety Six “and fired upon it for 36 hours, without scarce any intermission.”

[6] [Christopher Gadsden], Some Observations on the Two Campaigns against the Cherokee Indians, in 1760 and 1761. In a Second Letter from Philopatrios (Charleston, S.C.: Peter Timothy, 1762), 76, citing a letter dated “Camp at Ninety-Six, May 27th,” printed in South Carolina Weekly Gazette, 4 June 1760 (a newspaper that does not survive).

[7] The Horn Work, which was constructed between 1757 and 1759, eventually had a broad moat and drawbridge on its north side, but it’s unclear if these features were present in the spring of 1760. For more information on the Horn Work, see https://walledcitytaskforce.org/2014/10/17/lieutenant-hesss-horn-work/.

[8] In reference to express riders carrying messages from Fort Prince George to Charleston, the South Carolina Gazette, 4–11 October 1760, said “expresses commonly come from thence in 6 days.” In reality, the published details of other express riders throughout 1760 demonstrate the journey usually took between six and eight days. The speed limit within urban Charleston was first defined by section 18 of “An Act for keeping the Streets in Charles Town clean,” ratified on 31 May 1750; see the engrossed manuscript of that act at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH).

[9] South Carolina Gazette, 9–16 February 1760.

[10] The presence of a “lobby” on the second floor of the Council Chamber is mentioned on pages 33 (9 January) and 165 (11 April) of the manuscript Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, 6 January–31 December 1755, held at the National Archives of the United Kingdom, CO 5/471. A photostatic copy of this journal is available at SCDAH.

[11] South Carolina Gazette, 2–9 February 1760; Terry Lipscomb, ed. The Colonial Records of South Carolina: The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, October 6, 1757–January 24, 1761 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for SCDAH, 1996), 452 (available online from SCDAH).

[12] See, for example, section 23 of “An Additional Act to an Act entituled [sic] ‘An Act to prevent the Sea’s further encroachment upon the Wharfe at Charles Town,’” ratified on 23 December 1703; and “An Act for giving Freedom to a Negro Man named Arrah,” in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 33, 419–20.

[13] South Carolina Gazette, 9–16 February (Saturday). There was a second weekly newspaper printed in Charleston in 1760, the South Carolina Weekly Gazette, printed by Robert Wells, but very few editions survive from this era.

PREVIOUS: The Green Book for Charleston, 1938-1966

NEXT: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 4

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments