The Native American Land Cessions of 1684

Processing Request

Processing Request

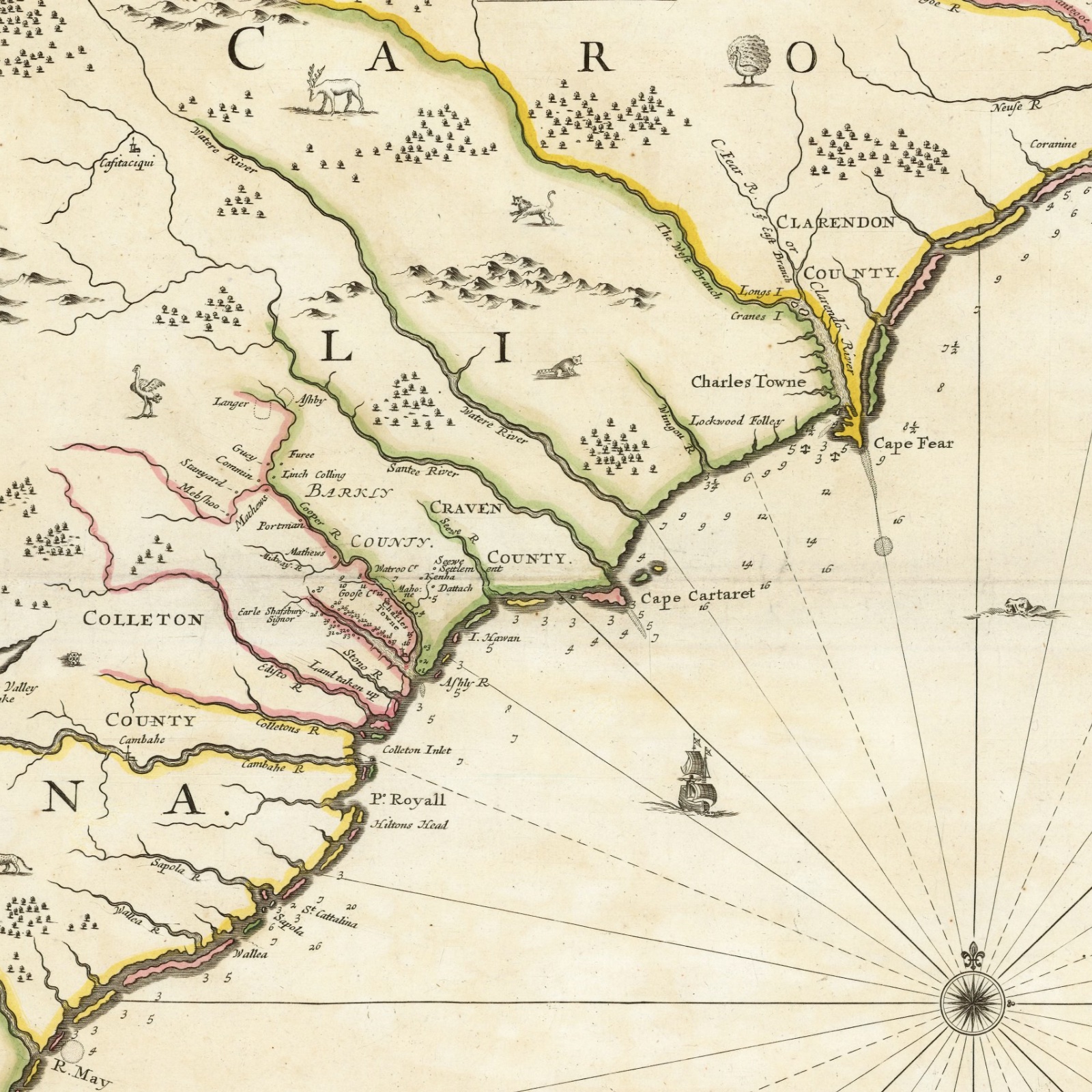

In the late winter of 1684, the leaders of eight Native American tribes in the Lowcountry of South Carolina surrendered their traditional homelands to English colonists. A series of documents ostensibly signed on a single day that February ceded Indigenous rights to millions of acres between the rivers Stono and Savannah, ranging from the Atlantic Ocean to the Appalachian Mountains. In this episode of Charleston Time Machine, we’ll explore the forces driving this historic bargain, parse details of the several transactions, and consider their collective impact on the native people in question.

The subject of today’s program was the culmination of a series of displacements in South Carolina that commenced with the Spanish settlement of Florida in the 1560s and accelerated during the English settlement of Carolina in the 1670s. The historical context preceding the Native American land cessions of 1684 is, therefore, a long and complex narrative far beyond the scope of a brief podcast essay. To set the stage for a poorly-remembered event that constitutes an important link in the chain of Carolina history, I’ll offer a very brief overview of the most salient points, each of which might be expanded by volumes of analysis. Furthermore, if you’re unfamiliar with the numerous distinct tribes that once formed the First People of the South Carolina Lowcountry, you’ll find an overview of that important topic in Episode No. 220.

More than four hundred years ago, as I described in Episode No. 215, the territory we call South Carolina formed the central part of the Spanish colony called La Florida. The creation of a Spanish settlement at Santa Elena, now Parris Island, in 1566 sparked friction with the native Escamacu people, later called the St. Helena tribe, who dominated the area surrounding what is now called Port Royal Sound. Santa Elena was then the capital of Spanish Florida, and its destruction in 1576 triggered a significant regional conflict, the Escamacu War, between colonists and the surrounding Indigenous population. Weakened by Native America resistance and clashes with English forces elsewhere, the Spanish withdrew from Santa Elena in 1587 and consolidated their resources at St. Augustine. Despite this evacuation, the effects of the Escamacu War and the enduring presence of Spanish Florida reshaped the population of what is now the southeastern corner of South Carolina. Most of the natives residing between the Savannah and Broad Rivers, their numbers in steep decline, quit that region during the last quarter of the sixteenth century and resettled farther to the north and west.[1]

In the 1660s, nearly a century after the Escamacu War, the Westo Indians of what is now northern Florida moved northward across the Savannah River into the largely vacant landscape formerly dominated by the St. Helena people. Subsequent Westo aggression toward neighboring Indigenous tribes sparked violent conflicts across the coastal Lowcountry as far north as modern Charleston Harbor. When English colonists arrived in the spring of 1670 to establish a settlement at Port Royal, representatives of the Kiawah people embraced the opportunity to gain protection from both the Westo and the Spanish. The Kiawah, who then lived on the southwest side of the present Ashley River, convinced the English to consider planting their proposed settlement to the north of Port Royal. According to the letters written by English settlers who interacted with members of the tribe in the spring of 1670, the Kiawah voluntarily ceded their home base to the English visitors, who established the first iteration of Charles Town on the West Ashley landscape now called Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site.[2]

Interaction with European visitors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries exposed the Native American population of this region to both illness and violence that steadily reduced their population. By 1670 and the founding of Charles Town, their numbers were evidently much smaller than they had been two hundred years earlier. Consequently, each of the several distinct tribes occupied a relatively compact territory and, individually, posed little threat to the expanding English settlement. The provincial government of South Carolina soon began granting to colonists large tracts of land to the south, west, and north of Charles Town, regions occupied at least seasonally by clusters of Native Americans. Some settlers apparently sought to mitigate their encroachment by compensating the Indigenous people. As I described in Episode No. 244, for example, English settlers in 1672 paid the Etiwan people to remove from the peninsula called Oyster Point (between the rivers Ashley and Cooper) to lands east of the Cooper.

The lack of a similar agreement on James Island led to problems for the Stono people two years later. When English settlers first arrived in this area, the Stono apparently inhabited both sides of what is now called the Stono River, on James and John’s Islands, and the stream we now call Wappoo Creek was then called Stono Creek. Settlers establishing homesteads on James Island soon complained that Stono Indians were taking English livestock without permission and disrespecting the boundaries of their private plantations. In response, South Carolina’s provincial government launched a brief “war” against the Stono in 1674 to punish their transgressions. The conflict reduced the tribe’s population to some unknown degree, and induced the survivors to withdraw to the southwest side of the Stono River.[3]

Similarly, English settlers pushing into the wilderness northwest of Charles Town during the early 1670s clashed repeatedly with the Kussoe people living around the headwaters of the Ashley River and southwestward to the “freshes” of the Edisto River, in what is now the southeastern part of Dorchester County. After a brief military campaign to punish Kussoe resistance, colonial officials convinced surviving members of the tribe to “for ever quitt and resigne” their traditional territory. The opposing factions gathered at an unknown location on the 10th of March, 1675/6 (on the Julian Calendar), to settle a formal deed of conveyance. “For and in consideration of a valuable parcell of cloth, hatch[etts] beads and other goods and manufactures,” the total value of which was not recorded, tribal leaders ceded their “territories, lands and royalties” to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, the Englishmen in London who claimed to own the vast colonial landscape. Approximately two dozen representatives of the Kussoe people, including several “cassiques” or chief men and a number of “captains” (among whom were several women) then made their respective marks with quill and ink on a piece of paper now held by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia.[4] Most of the Kussoe moved to new lands east of the Cooper River in 1676, like the Etiwan a few years earlier, settling approximately three miles above the mouth of the Wando River.[5]

Four years later, in the spring of 1680, the southern capital of Carolina officially moved across the Ashley River to the peninsula then called Oyster Point. The removal from old Charles Town to new Charles Town partially vacated the former home of the Kiawah people, but surviving members of the tribe did not rush back to the site they had voluntarily abandoned a decade earlier. English settlers had by that time seized control of the surrounding landscape on the southwest side of the Ashley River and pushed the Kiawah people farther afield. At some point before 1682—the details are now quite sparse—the much-reduced Kiawah tribe had migrated southward and established a temporarily residence on the island that still bears their name.[6]

By the time Joseph Morton became governor of the Carolina colony in the spring of 1682, the Native American population across the Lowcountry had reached a historic low. A contemporary writer, Robert Ferguson, published valuable estimates of each local tribe that same year. The largest, the Kussah people residing near the southwest reaches of the Edisto River, numbered fifty bowmen, or approximately 200 individuals. The smallest band were the Edisto, occupying their eponymous island, who counted just ten bowmen representing approximately forty people. The total number of Indigenous people living in the coastal plain between the rivers Santee and Savannah was therefore likely less than 1,800 individuals.[7] The contemporary population of White Europeans and enslaved Africans residing in the southern part of Carolina was similarly small, but plans unfolding in England at that moment sought to accelerate the colony’s expansion.

In the autumn of 1682, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina made an agreement with several Scottish adventurers who sought to establish a small colony of their own on the fringes of English Carolina. Twenty-five years before the formal union of Scotland and England under the denomination Great Britain, the Proprietors embraced the proposal for a separate Scots sub-colony because they believed it would bolster the security of Carolina against Spanish threats.[8] Their consent was predicated on two important conditions, however. First, the Proprietors were willing to accommodate the Scots within that colonial landscape as long as they did not crowd the settlements already planted within Berkeley County, around the rivers Ashley and Cooper (now the center of Charleston County). Accordingly, the Proprietors agreed to create additional county boundaries to the north and south of Berkeley County to reserve sufficient space for future English settlers. Second, the Proprietors recognized the need for advance negotiations with Native Americans who might be displaced by the proposed influx of Scots settlers. After more than a dozen years of managing a colonial enterprise, the English lords had apparently learned that an ounce of prevention was worth a pound of cure. Instructions dispatched from London to Carolina on the 21st of November 1682 informed Governor Morton of the proposed Scots colony and set in motion a chain of events leading to the Native American land cessions of 1684.

Prior to the arrival of the Scots settlers, wrote the Lords Proprietors, the Surveyor General of Carolina was to admeasure two new counties, one to the south of Berkeley County, called Colleton County, and one to the north of Berkeley, called Craven County. The proposed sub-colony of Scots was to be established in another, yet unnamed county, somewhere to the south of Colleton County, at their discretion. In whatever location the Scots chose, said the Lords Proprietors, the governor was to “instantly treat w[i]th ye Indians and buy the said land of them, w[hi]ch wee would have conveyed to us,” the eight Proprietors in England, by means of a formal legal instrument known as an “indenture of bargain & sale.” The Proprietors even specified most of the language of the document, which they insisted should include a formal acknowledgement of the Indians transferring both conceptual and physical custody of the premises. The Proprietors empowered Governor Morton or Maurice Mathews, a significant figure in the early years of South Carolina, to perform the required negotiations and to take possession of the lands ceded by the Indians. After this work was completed, the Lords required the governor to forward to London “copies of all deeds of sale you take from ye Indians.”[9]

Advance members of the Scots expedition came to Carolina sometime in 1683, traversed the coastal landscape, and selected a site to the south of newly-created Colleton County. The real estate in question was known to the English as Port Royal, in modern Beaufort County, but which the Spanish of that era still identified as Santa Elena in northern Florida. South Carolina’s provincial government then created a new county designation—Port Royal County—to encompass the site selected by the Scots and, according to orders from London, prepared to purchase the land from the Indians residing therein. In conversations not recorded among surviving documents, however, Governor Morton and his peers decided to expand the geographic scope of the proposed acquisition. While purchasing the Indigenous land rights within the boundaries of Port Royal County, to accommodate Scots settlers, the governor and his advisors decided to purchase similar rights from the tribes inhabiting Colleton County as well, to accommodate the inevitable expansion of English plantations to the south of Berkeley County.

At some point after the Scots had selected their site, Maurice Mathews led a small delegation that included three English men—John Dewar, Alexander Hall, and John Love—across the wilderness southwest of the Stono River to negotiate with various tribal leaders. Mathews, who arrived in Carolina in 1670, had apparently acquired some skill in one or more Native American languages during his long residence in the colony. The paucity of surviving texts from that era frustrates our ability to identify the Indigenous language(s) spoken within the Lowcountry of South Carolina, but it seems likely that resident tribes spoke several distinct dialects that might have shared a common root. To facilitate the negotiations led by Maurice Mathews, therefore, his traveling delegation included two Native Americans identified in subsequent documents as “Indian Interpreter.” Their names were recorded as Weena and Eupetoo, but no further information survives to confirm their tribal affiliation, age, or sex.

By the late winter of 1683/4, the Mathews delegation had visited and negotiated with the leaders of eight tribes residing within the broad coastal plain between the Stono River and the Savannah River. They met with the cassiques of the Ashepoo, Combahee, Kussah, Stono, Wimbee, and Witcheaugh people, and with the queens or chief women of the Edisto and St. Helena tribes. The White colonists and their Indian interpreters probably met these dignitaries within the respective townhouses that formed the communal center of each tribe, but documents to confirm such details do not survive.

Nor do we know the precise timing of the various negotiations. The entire extant record of this important chapter in South Carolina’s Native American history consists of eight tribal contracts and one joint cession, all dated 13 February 1683, which, according to the Julian Calendar in use at that time by the English, was, in fact, early in the year 1684 according the Gregorian Calendar we use today.[10] This chronological uniformity suggests several possible scenarios. It seems unlikely that Mathews and his delegation galloped from one tribal village to the next before sundown on a single winter’s day. It is possible, on the other hand, that Governor Morton summoned the leaders of eight Lowcountry tribes to gather in Charles Town to discuss the cession of their respective lands, and the 13th of February 1683/4 represents the date of a significant Native American conference in South Carolina. If such a meeting took place in the Carolina capital, however, Governor Morton would have almost certainly signed the documents. Instead, Maurice Mathews signed the extant contracts on behalf of the Lords Proprietors.

Considering these facts, I suspect that Governor Morton directed a clerk to prepare nine documents, all bearing the same date, before Mathews and his delegation set out from Charles Town to visit each of the several tribes in succession over a period of days. It is perhaps significant that the texts of the documents in question include nearly identical legal verbiage that conforms to the instructions sent by the Lords Proprietors in November 1682. It would have been far easier to prepare the hand-written text in Charles Town and to leave blanks in each document for the name of the tribe and a brief description of the property they ceded. Furthermore, the clerk or clerks performing this work almost certainly created three hand-written copies of each document—one for the chief of each tribe, one to be preserved among the records of South Carolina, and one to be sent to the Lords Proprietors in England.

We might imagine, therefore, that Maurice Mathews departed from Charleston at some point in the late winter of 1683/4 with a satchel containing as many as twenty-seven contracts written on large sheets of paper. His mission was to secure signatures from several tribal leaders confirming their cession of property rights in exchange for a relatively modest compensation. Within the communal townhouse of each tribe, Mathews and his entourage produced triplicate copies of an “indenture of bargain & sale,” an ink well, and a feather quill pen. He explained, with the aid of interpreters Weena and Eupetoo, that a large group of Scotsmen were coming to settle at Port Royal, and more European settlers and enslaved Africans would soon press farther to the southwest of Charles Town to create new plantations. Their intrusion into the wilderness inhabited by sparse numbers of Native Americans was now a foregone conclusion. The distant lords Mathews represented did not require the Indians to vacate their traditional lands, but simply to acknowledge the property rights of the approaching migrants.

At the conclusion of their respective negotiations, each of the eight tribes agreed to cede ownership of their territory in exchange for £10 sterling, a sum equivalent to roughly two thousand dollars in present money. It seems unlikely, of course, that each tribal leader independently and coincidentally arrived at the same sale price. The £10 specified in the sale documents probably represents a nominal sum offered by Mathews in conformity with similar legal transactions in contemporary England. Furthermore, the specified sum might not have been paid in a literal sense because the Indians living in the wilderness of South Carolina at that time had little use for English silver coins. Rather, the Mathews delegation might have rendered compensation using trade goods such as hatchets, beads, cloth, and other commodities, like those given to the Kussoe in 1676.

Each of the nine contracts executed in February 1683/4 includes around 1,000 words, the bulk of which echo the repetitive and redundant legal jargon one finds in formal English conveyances of that era. The only textual variation among these Native American deeds-of-sale, besides the name of the tribe, is the very brief description of the boundaries of the property sold. The Stono cession, for example, conveyed to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina and their heirs forever “all yt tract or parcell of land scituate lying & being in ye Province of Carolina bounded on ye east or south east wth the sea, on ye north or north east wth ye English settlement on ye west or north west wth ye great Ridge of Mountaines, comonly called ye Apalathean Mountaines and on ye south or south west wth Edistow and other countreys uninhabited.”[11]

Similarly, the “Queen of Edistoh” sold to the English lords all the land “bounding on the east or south east with the sea, on the north or north east with Stonoh, Kussoh and other land uninhabited on the west or north-west with the great ridge of mountaines comonly called the Apalathean Mountaines, and on the south or south-west with St. Helena Ashepow and other uninhabited land.”[12]

The remaining six tribal cessions echo the same pattern of vague boundary descriptions that render it difficult to visualize the precise location of the several properties in question. The ninth and final document purports to be a joint contract between the Lords Proprietors of Carolina and “ye Casiques Captaines and Cheifetaines of ye severall Countryes of Kussoe Stono Edistoh Ashepoo Cumbahe Kussah St. Helena and Wimbee.” That text includes a clerical error or perhaps a misunderstanding about whose land the Proprietors sought to purchase. The Kussoe, who sold their territory to colonists in 1676, did not participate in the tribal cessions of 1684, while the cassique of the Witcheaugh people, whose name appears nowhere else in the surviving records of early Carolina, signed both the joint cession of 13 February 1683/4 and an individual deed-of-sale bearing the same date.

Collectively, the leaders of the Ashepoo, Combahee, Edisto, Kussah, St. Helena, Stono, Wimbee, and Witcheaugh people jointly ceded to the Lords Proprietors “all yt tract or parcell of land scituate lying and being in ye Province of Carolina bounded on ye east or south east wth ye sea on ye north or north east wth Stonoh River and other lands now in ye possession of ye English on ye west or north west wth ye Great Rigdge of Mountaines commonly called ye Apalathean Mountaines, and on ye south or south west wth ye Westoh [i.e., Savannah] River towards ye sea and upwards wth lands not inhabited.”

In short, the joint tribal cession of February 1683/4 summarizes the geography of the eight individual sales made by the tribes named therein. As such, it represents a sort of insurance policy for the Lords Proprietors and the peaceful southward expansion of Carolina. Like the individual cessions, the joint contract mentions consideration money—“one hundred pounds lawfull money of England”—but the text includes no explanation of how that sum was to be divided among the eight participating tribes. This money, like that mentioned in the individual cessions, was likely a nominal consideration satisfied more practically by the distribution of valuable trade goods.[13]

At the end of each of the eight individual deeds-of-sale, the chief man or woman of the tribe made a small mark with quill and ink, while the joint cession includes the individual marks of sixteen Native Americans representing two leaders from each of the eight tribes. It seems unlikely that these sixteen men and women gathered under one roof in February 1683/4 to sign the joint deed of sale as a group. Rather, Maurice Mathews probably acquired their several marks successively as he and his entourage progressed across the landscape of Colleton and Port Royal Counties.

Having accomplished his mission of securing Indigenous property rights within the southernmost counties of English Carolina, Maurice Mathews returned to Charleston with duplicate copies of nine contracts signed by the leaders of eight Lowcountry tribes. The single date that appears on the documents in question might represent the date he commenced this errand, or perhaps the date he returned to Charles Town and delivered the manuscripts to the Register of the Province to be officially recorded.[14] Governor Morton sent one set of copies to the Lords Proprietors in London, but none of those documents is known to survive. The remaining copies created in 1684, bearing the authentic marks of the individual cassiques and queens, are also now lost. They were inserted into a record book in Charles Town that sustained damage during the ensuing century. Incomplete copies were made by a scribe near the end of the eighteenth century, after which time the original documents disappeared.[15] Fortunately, clerks in Charles Town transcribed faithful duplicate copies of all nine contracts between March and August of 1684. Those copies survive at the state archive in Columbia, and you’ll find photos of them in the text version of this podcast on the website of the Charleston County Public Library.[16]

No surviving documents record the sentiments of the hundreds of Native Americans impacted by the land cessions of 1684. They must have recognized, however, that the bills-of-sale marked by their leaders that February signaled the beginning of the end of their traditional way of life. The English offered a token compensation for the right to settle on their land, but did not evict the Indigenous population of what was then called Colleton and Port Royal Counties. There was no forced exodus like the infamous “Trail of Tears” that occurred farther west during the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

For the nominal price of £180 sterling (around $36,000 today), the Lords Proprietors of Carolina gained peaceable consent to control a huge swath of real estate measuring approximately fifty miles along the coast of modern South Carolina and stretching at least two hundred miles inland to the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Estimating conservatively, that’s approximately 10,000 square miles, or 6,400,000 acres. For his leading role in the campaign, Maurice Mathews received a generous gift from the Lords Proprietors. In November 1686, they granted him a tract of 1,000 acres “in consideration of his haveing purchased the lands from the Indians and takeing bills of sale for the same according to the forme by us sent him.”[17]

The trigger leading to the Native American land cessions of 1684 was a Scottish proposal to establish a sub-colony on the southern fringes of English Carolina. The creation of that settlement in 1684, called Stuarts Town at Port Royal, produced the opposite result envisioned by the Lords Proprietors. Rather than insulate the English colony from Spanish threats, the Scots settlement on the former site of Santa Elena aroused Spanish resentment and provoked reprisal. Violent raids in the autumn of 1686, perpetrated by Spanish soldiers from St. Augustine and their own Native American allies, decimated Stuarts Town and blazed a trail of destruction from Port Royal to Wadmalaw Island.[18] The Indigenous people living in that area suffered further loss, and many of the survivors moved farther to the north and west.

Although the events of the 1670s and 1680s diminished the population and territory of the Indigenous people residing within the Lowcountry of South Carolina, several of the tribes retained some presence and identity into the early years of the eighteenth century. The land cessions of 1684, though poorly remembered today, represent an important turning point in their collective history and merit a place in conversations about the state’s colonial legacy.

[1] For more information about the Escamacu War, see Gene Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1562–1751 (Southern Studies Program, University of S.C., Columbia, S. C. 1980), 171–83.

[2] For more information about the Westo and Kiawah, see Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 234–35.

[3] Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 304–6.

[4] The original document, dated 10 March 1675, in the twenty-eighth regnal year of Charles II (that is, in the year 1675/6 on the Julian Calendar then in use by the English), is recorded in South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Records of the Register of the Province (series S210001), volume 2 (1675–1709), 10. An abstract and an illustration of this document appears in Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds., The Proprietary Records of South Carolina, volume 2 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007?), 29–30. For a contextual discussion of this event, see Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 262–64. Note that both Waddell and Bates and Leland identify the document as dating from 1675.

[5] Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 10, 260–64.

[6] For more information about the Kiawah, see Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 222–24, 233–38, 305.

[7] Waddell, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry, 8–9, citing R[obert] F[erguson], The Present State of Carolina with Advice to the Settlers (London: John Bringhurst, 1682), 13–14.

[8] For a detailed description of the Scottish plan of 1682, see Peter N. Moore, Carolina’s Lost Colony: Stuarts Town and the Struggle for Survival in Early South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2022).

[9] Lords Proprietors to Joseph Morton, 21 November 1682 (three letters of that date), transcribed in William James Rivers, A Sketch of the History of South Carolina to the Close of the Proprietary Government by the Revolution of 1719, With an Appendix Containing Many Valuable Records Hitherto Unpublished (Charleston, S.C.: McCarter & Co., 1856), 397–400, citing British manuscripts now classified within CO 5/288 at the National Archives, Kew.

[10] Confirmation of date 13 February 1683/4 appears within the first line of text in each document, which specifies that the events in question took place in “the six and thirtieth year” of the reign of King Charles II. Officials in late seventeenth-century England calculated the beginning Charles II’s first regnal year from the day following the execution of Charles I, that is, 30 January 1648/9. The 13th of February in “the six and thirtieth year” of the reign Charles II is, therefore, 1684 on the modern Gregorian Calendar. Furthermore, the Julian Calendar was at that time nearly eleven days behind the Gregorian Calendar, so a modern equivalent of the actual date is closer to 24 February 1684.

[11] SCDAH, Records of the Register of the Province (series S210001), volume A (1682–1693), page 132. In this excerpt and throughout this essay, I have reproduced the original spelling found in the manuscript.

[12] SCDAH, Records of the Register of the Province (series S210001), volume A (1682–1693), pages 103–4.

[13] SCDAH, Records of the Register of the Province (series S210001), volume A (1682–1693), pages 137–38.

[14] Curiously, the Wimbee cession bears the date 20 February 1683/4 at the head and a concluding memorandum witnessing the formal transfer of custody on 13 February 1683/4.

[15] See SCDAH, Colonial Land Grants (Copy Series)(S213019), volume 38 (Proprietary Grants), pages 193–95 (Wimbee), 195–97 (Stono), 198–200 (Combahee), 200–2 (St. Helena), 203–4 (Kussah), 204–6 (joint cession). For more information about the early Records of the Register of the Province, see Charles H. Lesser, South Carolina Begins: The Records of a Proprietary Colony, 1663–1721 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1995), 428–34.

[16] See SCDAH, Records of the Register of the Province (series S210001), volume A (1682–1693), pages 103–4 (Edisto), 107–8 (Ashepoo), 115–17 (Witcheaugh), 131 (Wimbee), 132 (Stono), 134 (Combahee), 135 (St. Helena), 136 (Kussah), 137–38 (joint cession).

[17] A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Commissions and Instructions from the Lords Proprietors of Carolina to Public Officials of South Carolina, 1685–1715 (Columbia: Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1916), 72–73.

[18] For a detailed study of Stuarts Town and its demise, see Peter N. Moore, Carolina’s Lost Colony: Stuarts Town and the Struggle for Survival in Early South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2022).

NEXT: Free Indians In Amity with the State: A Legal Legacy

PREVIOUSLY: The Ghosts of Petit Versailles

See more from Charleston Time Machine