Bathing to Beat the Heat in Early Charleston, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

The cheapest and simplest form of bathing in early South Carolina was an ancient practice shared by numerous cultures around the world: one simply walked to the nearest creek, river, or beach and jumped in. Because specialized bathing garments did not exist until the early nineteenth century, most outdoor bathers swam in the nude. The rising popularity of swimming costumes in the nineteenth century did not eradicate skinny-dipping, however. Poor people and those bereft of modesty continued to swim au naturelle until agents of the law convinced them to do otherwise.

In the Carolina Lowcountry, two important factors shaped the local history of skinny-dipping to beat the summer heat. First, the practice of race-based slavery from 1670 to 1865 confined the Black majority of the population to a life of poverty and limited civil rights. Enslaved people of African descent who sought a bath to gain relief from the sweltering summer sun generally could not afford to procure proper bathing attire or the price of admission to a private bath house, which generally excluded persons “of color.” Their efforts to beat the heat and enjoy some aquatic recreation included the persistent risk of punishment and humiliation. Second, nude bathing probably occurred regularly within every local creek, river, and sea island from the beginning of colonization to the early twentieth century, but the vast majority of the evidence of such activity is confined to the vicinity of urban Charleston. Although enslaved people working on rural plantations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries probably took summer dips in nearby bodies of water, little evidence of their bathing survives in modern archives. In short, the predominantly urban record of outdoor swimming in the Lowcountry contains mixed references to both Black and White bathers, and most of this information could be extrapolated to the surrounding plantation landscape of the distant past.

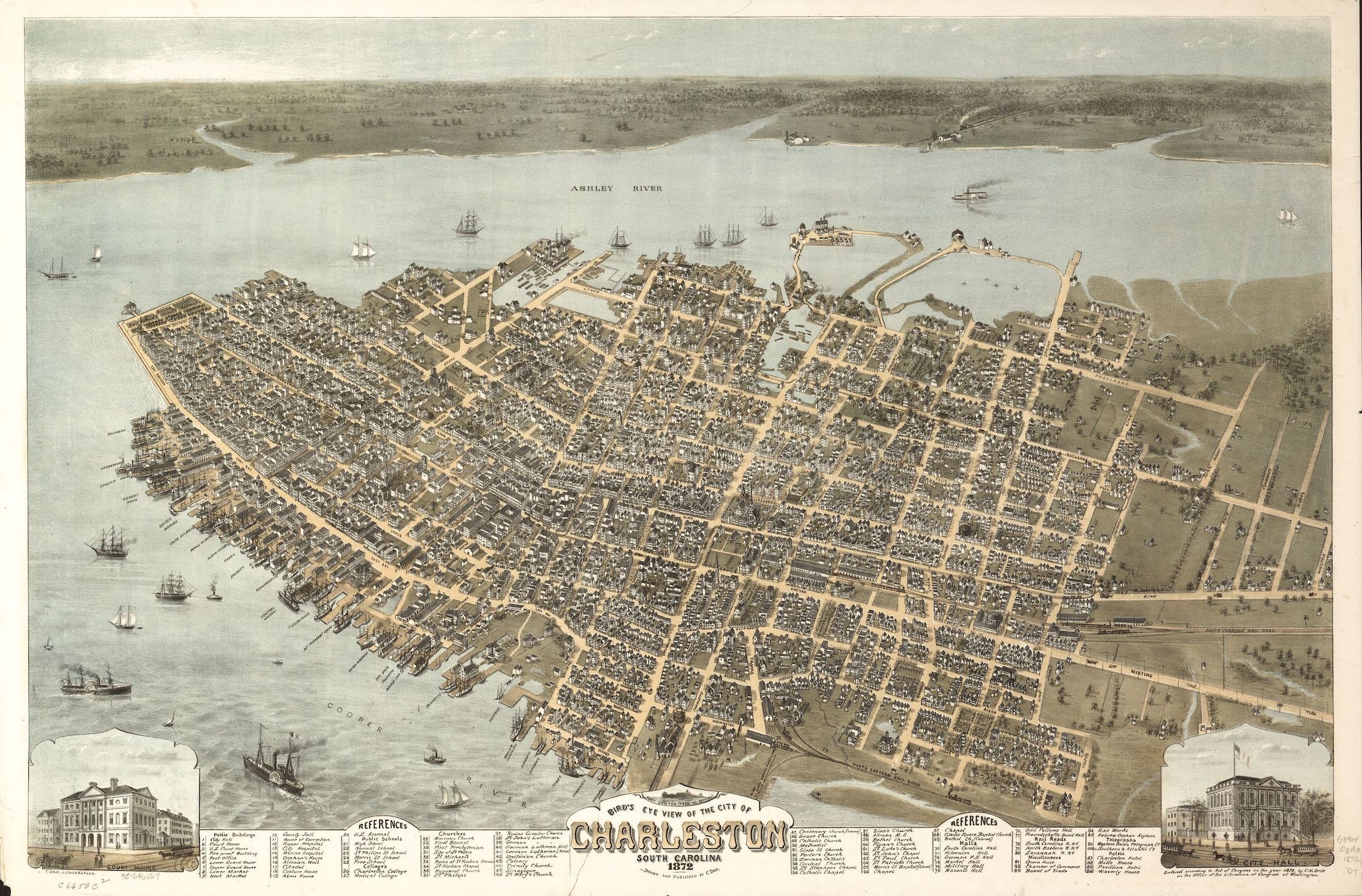

Within the confines of urban Charleston, from the colonial period to the twentieth century, there were always more eyes to witness the activities of boys and men of all ages seeking to cool their skin in the brackish water surrounding the peninsula between the rivers Ashley and Cooper. Numerous complaints about outdoor bathing survive in local newspapers, which commenced publication in January 1732. Having collected a large sample of such references, I’ve organized the material into a geographical survey of the most prominent urban bathing sites in centuries past.

Bathing at the Wharves:

The infrastructure of Charleston’s commercial waterfront commenced in the 1690s along the quay now called East Bay Street. In the early 1700s, the first few wooden wharves or bridges, as they were once called, projected into the Cooper River from the vicinity of the east end of Tradd Street. New wharves were eventually constructed farther to the south and north, and the continued addition of new wharves gradually transformed the waterfront into a much dryer landscape. During the early generations, however, vessels of all sizes could pass between the wharves with their bows pointing towards East Bay Street, anchoring in watery docks that attracted bathers from both ship and shore.

One of Charleston’s earliest newspapers, printed in May 1732, reported the death of “a Negro lad belonging to Mr. Fisher on the Bay,” who drowned “as he washing himself near Elliot’s Bridge” at the east end of Elliott Street.[1] A similar news item, published in 1775, reported that “a Negro boy belonging to Mr. Reed, of this town, was bathing in one of the docks” when “he was seized by a shark, of about twelve feet long, and so much hurt by a bite in the thigh, that he died soon after he was taken up.”[2] The presence of sharks in Charleston harbor during the warm summer months continued as a seasonal danger to bathers of later generations. Two large sharks, measuring twelve and nine feet long respectively, were caught along Charleston’s waterfront in the summer of 1793, prompting the local press to express hope “that persons who have been in the habit of bathing at the wharves, will discontinue the practice, for the present, or choose some other place for that diversion.”[3] When wharf-side anglers caught a pair of tiger sharks in May 1839, the editors of the Charleston Courier offered a succinct warning: “Bathers look out.”[4]

Bathing at White Point:

The modern landscape adjacent to Charleston’s iconic High Battery seawall and White Point Garden at the southern tip of the peninsula reflects several generations of planning and labor executed during the first half of the nineteenth century. Prior to that time, most of White Point was a militarized beachhead that was washed by the daily tides. The fortifications erected over the course of our colonial century were dismantled in the 1780s, and that demilitarization revealed an attractive bathing spot for those inclined to indulge in a practice still controversial in the late eighteenth century.

A correspondent to the Charleston City Gazette in 1797 provided a valuable narrative of his personal conversion to the practice of outdoor bathing. A physician had recommended it as a means of restoring his declining health, and he eventually came to appreciate the benefits of swimming in the nearby river. He developed a daily habit of bathing at the beach forming the southeasternmost point of the Charleston peninsula, but his routine was interrupted by the work of building the extensive seawall that became known as the Battery. Finding an alternative riverfront site nearby, probably around the south end of King Street, he was shocked to find the beach impregnated with “every kind of rubbish, oyster shells, broken bottles, rusty nails, &c.” that injured his feet and limbs. He acknowledged the utility of extending East Bay Street southward and erecting the protective seawall, but lamented that such work was simultaneously “depriving the people of the great benefit of bathing.” To accommodate future bathers, he suggested that Charleston’s City Council should erect “a few bathing houses” at White Point, “this being the most convenient spot in or about the city, for so useful a convenience.”

The author complained that the city leaders did not appreciate “how much it is the desire of the citizens to have such accommodations provided as to enable people of every description to avail themselves of the great advantage that can be derived from bathing in the salt water, which above all other remedies is the greatest preservative, as well as the greatest restorative of health.” Some of his neighbors were discouraged from the practice, however, by “the awful terror of sharks” as well as “beds of oysters, accumulated shells, bones, broken bottles, slates, brick-bats, and the scattered wrecks of vessels to annoy us, in every spot that the sea washes about the city.” Nevertheless, the anonymous bather opined that outdoor bathing had “a wonderful and happy effect in all warm climates . . . on almost all constitutions, by invigorating and bracing up the drooping and enfeebled frame of those who are oppressed and almost overpowered by the intense and continual heat of a long and sultry summer.”[5]

Successive hurricanes at the end of the eighteenth century destroyed several iterations of the Battery seawall between 1797 and 1804, and the construction of Fort Mechanic (at No. 19 East Battery Street) in the early 1790s further complicated that project. Despite the ongoing work at the site, swimmers continued to frolic in the waters adjacent to the rising seawall. A bather “at the lower end of Fort Mechanic” in July 1798, for example, lost “a small Masonic jewel, representing the square, compass, and sun,” and hoped “some young gentlemen bathing at the same place” might find and return it.[6] The stone seawall and promenading footpath was finally completed in 1818, but that achievement did not immediately scatter the bathing crowd. In the summer of 1824, a correspondent complained that genteel persons promenading on the Battery had “their delicacy shocked” by nude boys bathing in the water at the foot of the Battery, “sometimes to the number of twenty or thirty.”[7] “An enormous large shark” snapped up a dog swimming “within three or four feet of the Battery wall” in July 1827, prompting the editor of the Courier to publish “a caution to the youth who are daily bathing in that neighborhood.”[8]

Bathing at Cannon’s Bridge:

Most Charlestonians are aware that the intersection of Calhoun Street and Rutledge Avenue is prone to flooding during heavy rainstorms, especially during a rising tide in the nearby Ashley River. In the distant past, a bold tidal inlet from the river crossed Calhoun Street at this location and continued northward along the eastern edge of the campus of the Ashley Hall girls’ school. Post-Revolutionary War property developers in that neighborhood, historically known as Cannonborough, facilitated travel over the creek and adjacent mill pond by building earthen causeways leading to a plain wooden structure called Cannon’s Bridge. Men and boys, rich and poor, Black and White, were apparently in the habit of using the creek for summer bathing, and the increase of vehicular traffic across the bridge at the turn of the nineteenth century exposed thousands of travelers—including genteel women—to shocking sights. A grievance published in July 1804 by a correspondent called “Modestus” provides a vivid description of a typical summer’s day along the path of Cannon’s Bridge:

“At the close of the day, the scene . . . is seized upon and occupied by the most indecent collection of shameless individuals, that ever disgraced a civilized city—men of all ages, from the grey headed veteran in impudence, through all the stages of robust and brazen manhood, down to the little mischievous urchin, who is just taking his first lessons in impurity, and learning to strip off all modesty with his garments: men of all colors, from the deep dyed African, whose opaque skin would hide his blushes if he had any, through every shade of Sambo, Mulatto, Quartroon and Mestizo, to the white son of effrontery who has no blushes to hide, seize upon the passage to our city, and exhibit themselves in the naked deformity of impudence, along the sides of that avenue, through which beauty and modesty are to pass—they do not retire to some sheltered spot, where they might undress and hide themselves at once in the water; but in the open day, on the very border of the public road, on the very rails of the bridge, these men strip off the whole of their clothing, jump into the water, come out again, run to and fro, exhibit antic gestures, place themselves in indecent postures—when they see a carriage with ladies in it approaching, instead of retiring into the neighbouring water, they choose the most conspicuous spot upon the bridge, upon which they display themselves without shame, and sometimes shock the ears with immodest language, when they fail to attract the averted eyes of the blushing passenger.”[9]

Although “Modestus” begged the city government to suppress such activity, the “infamous nuisance” of “naked persons” bathing at Cannon’s Bridge continued for many decades. The “scandalous conduct” of the bathers, said another correspondent, rendered it “impossible” for ladies in the neighborhood “to approach their windows.” “Those who find themselves by surprise upon the bridge, and endeavour to avoid looking on one side, are insulted by a variety of expressions, noises, and other expedients, used to attract attention.” One of the bathers had even removed a plank from the bridge “to make a spring board to leap from into the water.” In June 1805, the Charleston Courier announced that the Attorney General of South Carolina was prepared to prosecute future bathers—that is, “fellows who can be so brutal as to offend female modesty in such a gross manner.”[10]

Beginning in the summer of 1807, the City of Charleston began publishing seasonal notices that the City Marshal was prepared to enforce a bathing curfew, to thwart those “in the habit of bathing in the day time, and exposing themselves entirely naked, at sundry places of publick resort and common thoroughfare, and particularly near Cannon’s Bridge, on the publick road, by which conduct common decency is violated, and great offence given to persons passing by, and to families residing in the neighborhood.” The curfew prohibited “bathing between sunrise in the morning and 8 o’clock in the evening, in any open place within the limits of Charleston.” White persons violating the prohibition would be referred to the state Attorney General for prosecution, but enslaved and free people of color would be arrested and lodged in the city’s notorious Work House, “to be tried afterwards and sentenced to condign [that is, appropriate] punishment.”[11]

Note that the city’s bathing curfew of 1807 did not criminalize skinny dipping in general, but sought to confine the practice to the darkest hours of the day. Despite this leniency, however, the problem persisted, especially at Cannon’s Bridge.[12] The drowning of a young boy at the popular swimming hole in May 1825 prompted a local father to publish a “solemn warning to parents” to restrain their children: “It is plain, that over and above the indecent exposure while bathing at so public a place (indeed scarcely a decent person bathes there, now,) it has become really dangerous, owing to the great number of rafties [i.e., raft-ties], stakes, &c. sunk near the bridge, and the broken bottles thrown into the pond.”[13]

“Sundry residents of the city and Cannonsborough” petitioned City Council in the summer of 1847 “for the abatement of a nuisance created on the part of the men and boys bathing in the pond adjacent to the cause-way” leading to Cannon’s Bridge. After a brief investigation, a committee of aldermen recommended the creation of an ordinance “prohibiting all indecent exposure in public places.” Council ordered further consideration of the measure to ban skinny dipping, but deferred taking legal action for another twenty-one years. In the meantime, the city government gradually filled the old mill pond and creek and replaced the causeway and bridge with a stable roadbed. Travelers driving, biking, and walking through the intersection of Calhoun Street and Rutledge Avenue today rarely encounter nude bathers along the roadside.[14]

Bathing on the East Side:

The residents of Charleston’s early suburbs on the east side of the peninsula, including Mazyckborough, Wraggborough, and Hampstead, probably swam in the Cooper River from the earliest settlement of those areas around the turn of the eighteenth century. That landscape was sparsely populated until the middle of the nineteenth century, however, and complaints about nude bathers were scarce before the construction of a railroad spur along the waterfront in the 1850s, terminating around the east end of Chapel Street. In August 1864, for example, the Charleston Courier published an editorial complaint about the “scandalous conduct of several white boys and negroes who are in the habit of swimming in the creeks running from the eastern portion of the city to the Northeastern Rail Road. Their conduct on Friday afternoon, whilst the train was going out with a car full of ladies, was of the most outrageous character, and the guilty parties if detected, should be severely punished. We hope the Captain of Police will take the matter in hand, and see that such indecent exposure is not witnessed again either upon the arrival or departure of the trains of this road, as has been frequently the case of late to our knowledge.”[15]

Despite the city’s half-hearted efforts to suppress skinny dipping at this location, the nuisance continued after the Civil War. In June 1885, for example, residents in the vicinity of East Bay and Reid Streets complained “of the conduct of boys and men, colored and white, at Mark’s Creek near the Northeastern Railroad. At all hours of the day they use the creek, which is near and in full view from Bay street, for bathing purposes, and their indecent conduct has been severely commented on. The trains of the Northeastern Railroad and Charleston and Savannah Railway pass and repass this point several times during the day, and the passengers are likewise subjected to the annoyance.”[16]

An old-timer named Sam Weller published in 1902 a brief memoir of his recollections of boyhood life in Charleston fifty years earlier. “In former years,” said Mr. Weller, “one of the pleasures most enjoyed by boys was swimming and many took to the water like ducks. A great rendezvous when the tide suited was a creek, which made in from Cooper River, running west parallel with the old Navy Yard, (latterly Railroad Accommodation wharf,) then north, passing in front of Vardell’s and Dereef’s wood yard wharves, then west for some little distance, parallel with Chapel street, then north until lost in the marsh south of the old Nowell place, giving at full tide about one-eighth of a mile to swim.”[17] The swimming creek described by Mr. Weller is now under the Columbus Street Terminal operated by the State Ports Authority, and is covered by hundreds of BMWs awaiting export to Europe.

Bathing on the West Side:

Most of the land at the west end of Broad Street, north of Tradd Street and south of Beaufain Street, was set aside by South Carolina’s provincial government in 1768 as a “common” for the use and enjoyment of the public in perpetuity. That broad landscape was a relatively useless tidal mudflat at the time, which the state ceded to the City of Charleston in 1783. The city government did little with the property for several generations besides sell and lease most of the real estate to private developers, until a post-Civil War lawsuit forced the city to transform the remainder of the 1768 common into public parks known as Colonial Lake and Moultrie Playground. Prior to that transformation, many citizens in the neighborhood were in the habit of skinny dipping in the tidal flows of the Ashley River, near the west end of Tradd, Broad, and Beaufain Streets. In fact, a complaint published in April 1839 specified that the “very great nuisance” was confined to the day of rest and relaxation afforded to working men and school boys. “We refer to the indecent and unbecoming practice of some boys bathing every Sunday in the pond immediately west of Rutledge and near the end of Beaufain-street. This annoyance is seriously felt by the residents in our vicinity, and is also very offensive to those who ride or walk along Rutledge between Broad and Wentworth-streets.”[18]

City engineers and enslaved laborers began transforming the tidal mudflat at the northwest end of Broad Street into a retention pond in 1856, complete with a flood gate to control the ingress and egress of the daily tide. That work eventually led to the formal creation of Colonial Lake in the early 1880s, which we’ll explore in more detail in a future program. Before the city decided to transform the site into a public park, however, the muddy tidal pool on the west side of Rutledge Avenue, between Broad and Beaufain Streets, drew locals seeking a safe haven for bathing and recreational swimming. In August 1869, for example, a White teenager drowned while bathing with friends at the west end of Beaufain Street, and in August 1872 a Black boy drowned while bathing “near the floodgate in the Rutledge-street pond.”[19] Sam Weller confirmed the popularity of this location in his aforementioned memoirs of 1902, which mentioned that “the Down-Town Bathers” frequently gathered “near the east end of Beaufain street” and other tidal locations on the west side of the peninsula.

After the Civil War:

As I described in Episode No. 84, the City of Charleston adopted an ordinance in April 1868 that criminalized “indecent exposure” and other offenses against conservative morality. In the years following, municipal authorities began cracking down on the traditional practice of nude bathing on the peninsula. In July 1872, for example, the Charleston Courier complained that young boys, Black and White, were too anxious to get into the water, and had “taken to exposing themselves in too conspicuous places. Forgetting that the water fronts, principally in the western portion of the city, are much frequented by promenaders [sic] these sultry afternoons, they strip off their clothing and take an airing, preparatory to a plunge, so as to be seen at some distance. The policemen on Saturday very properly drove these nude chaps from the foot of Line, Washington and Broad-streets, where they will not be allowed in future, save after night fall.”[20]

Under pressure to confine, if not eradicate, skinny dipping on the peninsula, city authorities responded in August 1872 by published the following list of places where free bathing would be tolerated: “On the West. Extreme end of Broad street, beyond the rafts [of trees floated down the river to the saw mills], and Gadsden’s Creek. On the East: Vardell’s Creek [now Grace Bridge Street] and the Central Wharves of John Fraser & Co [at the east end of Cumberland Street]. The police are instructed to arrest all persons found bathing elsewhere.”[21]

The police department published annual reminders of these designated locations in several subsequent years, but complaints about the “noise and obscenity” of bathing on the docks and other unauthorized sites continued.[22] In the sultry summer of 1888, city authorities acknowledged that the root of the continuing nuisance was poor boys, Black and White, who had no other relief from the summer heat. Some continued skinny dipping in the docks between the wharves along East Bay Street, running the risk of arrest, theft of their clothing, and injury from seasonal sharks.[23] Others, described as “the uptown boys, mostly butcher boys,” were in “in the habit of bathing in a creek at the corner of Line and President streets” in July 1888. Their bathing attire, said the News and Courier, was “not of the most fashionable, but rather of a primitive style. The people residing in the vicinity naturally objected and a squad of policemen was yesterday detailed to break up the swimming pool. The officers were sent in citizens’ clothing, and reached the scene when about a dozen or more boys were in swimming. A small boy on shore, however, ‘caught on’ to the racket and shouted ‘cops!’ The swimmers took the hint and scattered in every direction, through the marsh, in the river, and through fields and forests. The police succeeded in capturing their clothing only, and this was taken to the Station House.”[24]

The solution to all of these complaints, offered by municipal authorities in final years of the nineteenth century, was to construct one or more “free” bathing houses in the rivers Ashley and Cooper. An ordinance passed in 1889 created a board of Bathing House Commissioners and one small wooden bathing house, standing on pilings in the Ashley River, was devoted to White patrons only. Following the opening of that facility at the west end of Broad Street in June, Charleston’s chief of police warned the public “that bathing in public places will not be permitted hereafter.”[25] Plans to open a similar free bathing house for the use of Black citizens at the east end of Pinckney Street failed, however, when the proprietor of the Union Wharves contested to the ownership of the water lot in question.[26]

The free bathing house at the west end of Broad Street lasted for just two seasons, but a replacement at the west end of Tradd Street, adjacent to Chisolm’s Mill, opened in June 1895. At that time, the city threatened to launch a crusade against nude bathers frequenting the wharves. “The public love of the nude,” said the chief of police that summer, “does not extend to naked urchins disporting themselves on the docks and wharves of the city.”[27] Like its predecessor, however, the West End Bath House of 1895 was a segregated facility opened to White citizens only. At the dawn of the twentieth century, locals continued to complain about Black boys bathing in the “altogether” at the west end of Tradd Street, near Rutledge Avenue, where “the boys spent much of the time out of the water, which made the nuisance all the more annoying because of the populous thoroughfare.” A police officer on the scene reportedly witnessed and permitted the activity, which the editors of the Charleston Evening Post opined “was probably induced by his desire to have the boys clean themselves, but at the same time the residents and those who were forced to witness the exhibition would rather have not seen the show.”[28]

A few years later, in 1914, the Commissioners of Colonial Lake embraced the notion that their brackish pool offered “the only safe swimming and bathing place in the City of Charleston,” and encouraged boys to cavort in its shallow waters. Those who swam in the tidally-influenced pond soon became sick with typhoid fever, however, on account of the sewer drains emptying into the creek feeding directly into Colonial Lake.[29] That drainage conundrum was finally amended after World War II, but the city has not endorsed swimming in that water park for more than a century.

The rise of indoor plumbing in urban Charleston in the early twentieth century rendered outdoor bathing less of a necessity and more of a recreational pursuit. The contemporary proliferation of automobiles also made it easier for citizens to leave the peninsula to visit nearby seashores and other wild locations to enjoy summertime sport without offending their urban neighbors. As late as 1931, however, city authorities conceded that “there is no doubt that some river bathing is done in Charleston.” The pond to the east of West Point Mill was used as a “swimming hole” in the early twentieth century, said a news report, and sites along the Cooper River also served as “a ‘sub rosa’ bathing pool for some of the younger negroes of the city. The activities of this group are, as a rule, hidden from view, but occasionally a citizen rounds a curve on the waterfront and sees a dozen ebony hued bodies, sans clothes, disporting themselves in the dark waters of the river. Occasionally, too, the police are called to break up such a group which had shocked the sensibilities of some staid citizen, but outside of these interruptions, river swimming continues without regulation.”[30]

This survey of outdoor bathing in Charleston’s past represents a series of snapshots of different locations and eras, but some listeners might wonder why I haven’t mentioned the several outdoor bathing houses of various sizes that existed in the rivers Ashley and Cooper during the nineteenth century. Those curious commercial structures, which represented a different solution to the problem of beating the summer heat, catered to a smaller, more affluent portion of the community, and deserve a deep dive of their own. I plan to wade into that colorful story in a future summer program. In the meantime, I hope you all stay cool and keep your head above water!

[1] South Carolina Gazette, 20–27 May 1732, page 3.

[2] South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 26 September 1775, page 5.

[3] [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 10 August 1793, page 3.

[4] Charleston Courier, 27 May 1839, page 2, “Sharking.”

[5] See the letter from “A. C.” in City Gazette, 13 July 1797, page 2.

[6] City Gazette, 11 July 1798, page 4, “Lost.”

[7] Courier, 21 July 1824, page 3, “(Communication).”

[8] Courier, 9 July 1827, page 2, “Caution to Bathers.”

[9] See the letter from “Modestus” in Courier, 17 July 1804, page 2. I have reproduced the spelling used in the original source.

[10] Courier, 13 June 1805, page 3.

[11] Courier, 25 May 1807, page 3, “Notice.”

[12] City Gazette, 26 July 1810, page 4, “City Council, July 23d, 1810.”

[13] City Gazette, 20 May 1825, page 3.

[14] For more information about Cannon’s Bridge and the adjacent landscape, see Christina Rae Butler, Lowcountry at High Tide: A History of Flooding, Drainage, and Reclamation in Charleston, South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2020), 6, 54–55, 96.

[15] Courier, 15 August 1864, page 1, “Scandalous Conduct.”

[16] Charleston News and Courier, 8 June 1885, page 8, “A Nuisance.”

[17] News and Courier, 9 March 1902, page 11, “Boys of Fifty Years Ago.”

[18] Courier, 27 April 1839, page 2, “(For the Courier.) Nuisance.”

[19] Courier, 13 August 1869, page 1, “A Distressing Case”; Courier, 2 August 1872.

[20] Courier, 1 July 1872, page 1, “Public Bathing.”

[21] Charleston Daily News, 25 July 1872, page 4, “Board of Health”; Daily News and Courier, 3 August 1872, page 2, “Municipal Notices”; Daily News and Courier, 5 August 1872, page 2, “Municipal Notices.”

[22] News and Courier, 16 July 1873, page 2; News and Courier, 1 June 1874, page 4, “Talk about Town”; News and Courier, 2 June 1874, page 2, “Municipal Notices.”

[23] News and Courier, 10 July 1888, page 8, “Salt Water Everywhere.”

[24] News and Courier, 24 July 1888, page 8, “Bathing Houses Wanted.”

[25] News and Courier, 14 July 1889, page 8, “All Around Town.”

[26] News and Courier, 31 July 1889, page 8, “The East Side Bathing House”; News and Courier, 10 July 1890, page 8, “The Small Boys of Charleston.”

[27] News and Courier, 5 June 1895, page 8, “All Around Town.”

[28] Charleston Evening Post, 28 June 1900, page 5, “Bathing in Public.”

[29] City of Charleston, Year Book, 1914, 289–90.

[30] News and Courier, 29 December 1931, page 2, “Bathing House Commission.”

NEXT: John Champneys and His Controversial Row, Part 1

PREVIOUSLY: Bathing to Beat the Heat in Early Charleston, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine