A Veteran’s Story: Caring for the Family of Sergeant William Jasper

Processing Request

Processing Request

Veterans Day is a national holiday that was created in the twentieth century, but the roots of our collective acknowledgement of soldiers’ sacrifices dates back many generations to the dawn of the United States. Today we’ll use the story of one veteran’s forgotten family—the wife and children of the famous Sergeant William Jasper—to trace the evolution of local, state, and national efforts to assist the survivors our nation’s brave defenders.

Even before the creation of the United States of America in 1776, each of the former British colonies had inherited from the mother country the tradition of providing government or “public” assistance to injured veterans and to the survivors of men who died in the course of military service. The commencement of the American Revolution in 1775 was a leap of faith for those who shouldered weapons and wagered their lives and personal fortunes to secure independence from colonial oppression. From the beginning of that conflict, state governments across the new nation offered payments to those maimed and killed, as well as promises of future compensation, as a means of encouraging men to enlist in the fight and take the necessary risks. The nation’s credit and trustworthiness was never so important than during this time of existential crisis.

Here in South Carolina, the dispensation of government assistance to soldiers maimed and killed in during the American Revolution commenced in 1778, if not earlier. Our knowledge of this matter is clouded by the paucity of extant government records from the war years, owing to the vicissitudes of that eight-year conflict. The archival record of state moneys paid to Revolutionary War veterans and survivors improves as the years progressed beyond the war and into the nineteenth century. At our state archives in Columbia, you’ll find a robust but incomplete collection of accounts, petitions, and reports that now form an invaluable body of information about the people who served in the war and their families.

Here in South Carolina, the dispensation of government assistance to soldiers maimed and killed in during the American Revolution commenced in 1778, if not earlier. Our knowledge of this matter is clouded by the paucity of extant government records from the war years, owing to the vicissitudes of that eight-year conflict. The archival record of state moneys paid to Revolutionary War veterans and survivors improves as the years progressed beyond the war and into the nineteenth century. At our state archives in Columbia, you’ll find a robust but incomplete collection of accounts, petitions, and reports that now form an invaluable body of information about the people who served in the war and their families.

South Carolina was not alone in this remunerative practice, of course, as each of the thirteen states that had participated in the Revolution struggled to repay its debts to those who made all sorts of sacrifices during the war. For the most part, these issues were addressed at the state level, with relatively little assistance from the nascent federal government of the United States sitting in Philadelphia, and then Washington, D.C. In the middle of the War of 1812, however, the Congress of the United States created the “Committee on Pensions and Revolutionary War Claims” in 1813. In 1825, Congress reconfigured this body as two separate committees, one on “Military Pensions” and one on “Revolutionary Claims.”[1] These congressional committees, which continued for several decades, established a precedent for federal aid to veterans that continued through several successive wars and eventually evolved in to the present United States Department of Veterans Affairs.

Returning to our focus on South Carolina, we can view a microcosm of the evolution of the state government’s assistance by tracing the story of one veteran and his family. Since the state’s aid has always focused on the “common” soldier with limited private wealth, we need not look for government payments to the well-known “heroes” of the Revolution like General William Moultrie, General Isaac Huger, Lieutenant Colonel Barnard Elliott, and other affluent men. Instead, let’s trace the aid distributed to the family of a private soldier who climbed to the rank of sergeant, William Jasper.

The name of Sergeant William Jasper is found in nearly every published narrative of South Carolina history since the American Revolution, but in reality, we know little about the man behind the famous name. Here, we could take a diversion into the murky labyrinth of Jasper family genealogy, but I’ll resist the temptation and save that discussion for a later time. William Jasper is remembered as the brave soldier who stood atop the American fortifications at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28th, 1776, and again at the Siege of Savannah on October 9th, 1779, to rally his comrades to persevere in the face of an overwhelming British artillery barrage. Sergeant Jasper unfortunately received a mortal wound during the action at Savannah, but the legend of his heroic deeds took root and grew over successive generations. Even in the twenty-first century, conversations about the Revolutionary War in South Carolina and Georgia inevitably include a mention of William Jasper.

Sergeant Jasper made the ultimate sacrifice for his adopted country, but what happened to his family after his demise? Later sources indicate that Jasper’s death in 1779 left behind a family consisting of a widow and three children—specifically, two daughters and a son.[2] We know very little about these people because they were relatively poor, and people of limited means rarely leave behind a trail of private records for later generations to study. By following the public paper trail of government assistance afforded to these survivors, however, we can uncover some interesting facts about the Jasper clan and simultaneously gain insight into the limits of public welfare in the early years of the United States.

In the decade between 1780 and 1790, the State of South Carolina made at least five contributions to the family of the late Sergeant William Jasper. A little more than three months after Jasper’s death, on January 30th, 1780, the treasurer of South Carolina issued a payment to help support his family. Under the heading “Annuities to persons hurted in Service of the State, the treasurer “p[ai]d Sergt. Jasper’s widow” one hundred Spanish dollars, or £162.10 in South Carolina currency, “p[e]r Gov[erno]rs order . . . towards the support of herself & children.” The British Army captured the capital of South Carolina a few months after that payment, and the martial confusion rendered the state relatively powerless to extend further aid for the duration of the war.[3]

In the decade between 1780 and 1790, the State of South Carolina made at least five contributions to the family of the late Sergeant William Jasper. A little more than three months after Jasper’s death, on January 30th, 1780, the treasurer of South Carolina issued a payment to help support his family. Under the heading “Annuities to persons hurted in Service of the State, the treasurer “p[ai]d Sergt. Jasper’s widow” one hundred Spanish dollars, or £162.10 in South Carolina currency, “p[e]r Gov[erno]rs order . . . towards the support of herself & children.” The British Army captured the capital of South Carolina a few months after that payment, and the martial confusion rendered the state relatively powerless to extend further aid for the duration of the war.[3]

Shortly after the end of the Revolutionary War, on April 4th (or 11th), 1783, the treasurer made another payment to William Jasper’s widow that recorded her name. Under the heading of “Continental Contingencies,” the state paid £4.13.4 sterling to “Eliz. Jasper for services rendered by her late husband.”[4] Just over a year later, on June 2nd, 1784, “Elizabeth Jesper” [sic] married Christopher Wagner at St. John’s Lutheran Church in Charleston.[5] From that point forward, Mr. Wagner, a poor drayman or wagoner in the city, was responsible for supporting the widow of the famed sergeant.

But the State of South Carolina was not yet finished dispensing aid to the survivors of William Jasper. On May 9th, 1785, the state treasurer paid an “annuity” of £8.15 sterling to Mrs. Elizabeth Wagner that was earmarked “for the children of Serjt. [sic] Jasper.” One year later, on May 18th, 1786, the state made a similar payment of £4 sterling “for [the] children of Wm. Jasper Sergt. in 2nd Regt.”[6] Here the paper trail of financial payments to the Jasper children ends. The state’s ability to render aid to this and other worthy families appears to have been curtailed in the late 1780s, as the record of annuities paid during this era is quite slim. [7]

The next piece of this story dates from 1790, but it was set in motion years earlier. In the spring of 1778, more than a year before the death of Sergeant William Jasper, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified an act promising two hundred acres of free land to every soldier who completed his term of enlistment during the war. “In case it shall so happen that any such soldier be slain or depart this life during this contest,” however, the law provided that “his heirs shall be entitled to the said two hundred acres of land.” That 1778 promise of free land was officially set in motion by another state law ratified in 1784, which empowered local commissioners to receive the applications of South Carolina veterans for their two hundred acres.[8]

William Jasper’s principal heir was his son, William Jr., who may have been born on Sullivan’s Island in 1777 or 1778. More than a decade later, in 1789, someone acting on junior’s behalf applied to the state government to claim the bounty land due to his late father’s estate. The state then directed the surveyor general to locate and measure a parcel of two hundred acres and to create a plat thereof. The property allotted for William Jasper Jr. consisted of vacant land on Treadwell’s Swamp, on the northeast side of the Little Pee Dee River, near Galivants Ferry in modern Horry County.[9] Governor Charles Pinckney signed the land grant in early 1790, at which time the heir would have been a boy of twelve or thirteen years.

Whether or not William Jasper Jr. ever claimed or settled or farmed this land is unknown to me. As a young man, he apparently went to sea and traveled around the world. In the spring of 1810, he married Esther Shepard in Beaufort, North Carolina, where he apparently lived for a while.[10] Shortly thereafter, the young couple was back in Charleston, sharing a rental house on the east side of King Street, between Broad and Tradd Streets, with John Francis Plumeau, a native of the French island colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).[11] There William Jasper Jr. died on July 30th, 1819, aged around 42 years, and was buried in the cemetery adjoining Bethel Methodist Episcopal Church, at the southwest corner of Calhoun and Pitt Streets.[12]

Antebellum writers state that William Jasper had two daughters, but the name of only one of them has survived to the present. Elizabeth Jasper was apparently named for her mother, and was likely born before the commencement of the Revolutionary War. Eliza, as her name frequently appears in extant public records, was married at least once, to man named Brown, but the family was so poor that they left behind no private records, and I haven’t been able to determine her husband’s name. In the spring of 1820, a local hostler named John Atchinson (also spelled Atchison) sued Eliza J. Brown over an unpaid I.O.U. amounting to $70.87. Because married women were virtually invisible to the law during this era, Atchinson’s suit probably indicates that Mrs. Brown was a widow by 1820, at which time she would have been around fifty years old.

Eliza Jasper Brown probably had children, but we know nothing of their identities or lives. A list of unclaimed letters waiting at the Charleston post office, published in December of 1824, includes the name William Jasper Brown, but we have no confirmation of that man’s relationship—if any—to the family of Sergeant Jasper.[13] Regardless of the details of her family situation, however, we can be certain that Eliza Brown was living in obscurity in Antebellum Charleston. During an era when the memory of brave Sergeant Jasper was being celebrated in textbooks, patriotic speeches, and celebratory toasts, that veteran’s last surviving child was struggling to make ends meet in the heart of Charleston.

At some point during the sultry days of early June 1836, Eliza Jasper Brown walked through the door of the Charleston Poor House, then located on the west side of Mazyck (now Logan) Street, and asked for food. The steward of the institution may have provided her with a meal on that day, but he also helped her to complete an application for more regular assistance in the form of rations. The Poor House was both a residential facility for white paupers too infirm or disabled to support themselves, and a distributor of weekly rations to poor folks who resided elsewhere within the city. These “outdoor pensioners,” as they were called in the institutional records now held at CCPL, received three times each week a quantity of beef and bread that constituted one ration. When the affluent gentlemen who formed the Commissioners of the Charleston Poor House convened their weekly meeting at the institution on June 15th, 1836, the minutes of their proceedings include the following brief note: “The application of Mrs. Eliza Brown for rations was consider’d and One Ration granted.”[14]

At some point during the sultry days of early June 1836, Eliza Jasper Brown walked through the door of the Charleston Poor House, then located on the west side of Mazyck (now Logan) Street, and asked for food. The steward of the institution may have provided her with a meal on that day, but he also helped her to complete an application for more regular assistance in the form of rations. The Poor House was both a residential facility for white paupers too infirm or disabled to support themselves, and a distributor of weekly rations to poor folks who resided elsewhere within the city. These “outdoor pensioners,” as they were called in the institutional records now held at CCPL, received three times each week a quantity of beef and bread that constituted one ration. When the affluent gentlemen who formed the Commissioners of the Charleston Poor House convened their weekly meeting at the institution on June 15th, 1836, the minutes of their proceedings include the following brief note: “The application of Mrs. Eliza Brown for rations was consider’d and One Ration granted.”[14]

In the course of her regular visits to Poor House, Eliza Brown, aged around 65 years in 1836, might have chatted with the staff and revealed part of her life story. Perhaps the steward of the institution made polite inquiries into how Mrs. Brown came to be in state of need. We might imagine that Eliza at some point proudly mentioned her famous father, the celebrated William Jasper, and also recounted the demise of her poor mother, siblings, husband, and children. Word of Sergeant Jasper’s impoverished daughter spread around town, and in the summer of 1837 an anonymous admirer of the famed hero of the American Revolution tracked down and interviewed Mrs. Brown.

The context of this “interview,” for lack of a better term, requires a bit of explanation to establish the proper context. In July of 1837, an engraving shop on Broad Street in Charleston had on display a series of recent oil paintings depicting scenes from the American Revolution created by local artist John Blake White (1781–1859). These canvases, which now hang in the United States Senate, included a depiction of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island in 1776 (complete with Jasper shimmying up a flagpole) and a painting of brave Sergeant Jasper rescuing American prisoners from a British camp.[15] According to a correspondent calling himself “Ramsay” in the Charleston Southern Patriot, Mr. White’s painting of this Jasper scene was prompted by the suggestion of a “venerable friend” who possessed “a fond admiration for Carolinian history” and felt “a luxuriant delight . . . in lingering over the patient endurance and heroism of her sons in the war of the Revolution.” That same patriotic zeal, said “Ramsay,” also moved his anonymous friend “to make inquiries after the descendants of the gallant soldier, whose prowess thus ennobles our annals.” In short, an unknown admirer found Elizabeth Jasper Brown living in poverty in 1837, and reported part of his conversation with her to the local newspaper on August first:

Perhaps it will be news to many, to hear that a daughter of the brave Sergeant is still alive, and a resident and a native of Charleston. She complains not, yet fortune has not been profuse in her gifts to her, and it is somewhat remarkable, that not one of the family or descendants of this brave soldier ever received a cent of aid, from the State or Federal Government. She states that when her father, Sergeant Wm. Jasper, was killed at Savannah, on the 17th of September [sic; October 9th], 1779, he was then about 45 years of age, and left a widow and 3 children, and of these she only survives.—She further states that her father was a Native of Ireland—that he married a lady in the interior of this State, and that all his children were born here. Many other interesting particulars are still fresh in her memory, in regard to these times, the details whereof it is not deemed expedient to give now. In the mean time, while we admire the character of Jasper—while we contemplate with delight the close art, blended with the native fire of our own Artist, so well displayed in this rich and charming picture, would it not be well to pay a just debt due to Jasper, by applying to Congress to make the last days of his now aged daughter comfortable, by giving her the benefits provided by the pension law, for persons of her description.[16]

Thanks to the publication of this brief article, which does not mention specifically the name of Eliza Brown, news of William Jasper’s impoverished and now aged daughter spread throughout the community. People in positions of power and influence took notice, and a course of action was determined. Hugh Swinton Legare (1797–1843) had recently been elected to represent South Carolina in the United States Congress, and was about to return to Washington D.C. for his second session in the House of Representatives. Now that the federal government had a robust pair of committees to deal with pensions and claims related to the Revolutionary War, it seemed logical to present the case of Sergeant Jasper’s needy daughter to the consideration of the highest power in the nation.

Thanks to the publication of this brief article, which does not mention specifically the name of Eliza Brown, news of William Jasper’s impoverished and now aged daughter spread throughout the community. People in positions of power and influence took notice, and a course of action was determined. Hugh Swinton Legare (1797–1843) had recently been elected to represent South Carolina in the United States Congress, and was about to return to Washington D.C. for his second session in the House of Representatives. Now that the federal government had a robust pair of committees to deal with pensions and claims related to the Revolutionary War, it seemed logical to present the case of Sergeant Jasper’s needy daughter to the consideration of the highest power in the nation.

On the afternoon of Monday, March 5th, 1838, Representative Hugh Swinton Legare presented a resolution on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives to consider granting a pension to Mrs. Elizabeth Brown, daughter of Sergeant William Jasper, “who gallantly fell at the battle of Savannah, after rendering the most important service to his country.” A local newspaper report of this action, published just a few days later, stated that Mr. Legare had “wished to make some remarks” about the importance of the case at hand, but the rules of the House required him to pass it first to the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions for consideration.[17] Two weeks later, on March 20th, Elisha Whittlesey of Connecticut made a motion on the floor of the House that the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions be discharged, or relieved, from the duty of considering several cases referred to them, including that of “Mrs. Brown (daughter of Sergeant Jasper).” The House voted to approve this request, and the petition for Eliza’s pension was quietly laid aside.

Hugh Legare might have been disappointed by the Congressional rejection of his appeal for a pension for Eliza Brown, but he was not deterred. On April 5th, 1838, he stood on the House floor and offered a resolution “That the Committee on Revolutionary Claims be instructed to inquire into the expediency of granting to Mrs. Brown, daughter of Sergeant Jasper, the commutation pay of a subaltern officer, or such other compensation as she may be, in the opinion of the committee, entitled to, under the laws and practice of Congress.” Three weeks later, however, Representative Joseph Underwood of Kentucky made a motion to reject this appeal, and a majority of his distinguished colleagues agreed. The United States House of Representatives ordered “that the Committee on Revolutionary Claims be discharged from the consideration of the case of Mrs. Brown, daughter of the celebrated Sergeant Jasper, of the revolutionary army; and that the said case do lie on the table.”[18]

Following the unsuccessful attempt to gain federal assistance for Elizabeth Jasper Brown, her situation remained unchanged for the next several years and she passed into the seventh decade of her life in South Carolina. The surviving records of the Charleston Poor House indicate that she continued to receive a regular diet of simple rations from that institution into the 1840s, but we know little else about her life. She was living in obscurity and in want, but she was not totally forgotten.

On November 30th, 1844, in Columbia, state representative and former Charleston mayor Henry Laurens Pinckney (1794–1863) presented to the South Carolina House of Representatives “the petition of Elizabeth Brown, daughter of the late Serjeant Jasper, praying for a pension.” The House dutifully referred the petition to a committee, which submitted its report on December 4th. The following day, the committee reported its favorable opinion of the plan to grant a pension to Jasper’s daughter. Mr. Pinckney then stood and offered the following resolution: “That the report of the Committee on Pensions upon the petition of Mrs. Brown be recommitted to that committee with instructions to report a bill allowing her a pension of sixty dollars during the remainder of her life.” Representative John Izard Middleton (1785–1849) then stood and offered an amendment to the resolution. He moved that the words “sixty dollars” be stricken out, and the words “one hundred dollars” be inserted in their place. After a vote, the amended resolution was adopted, and the committee began to draft a bill.[19]

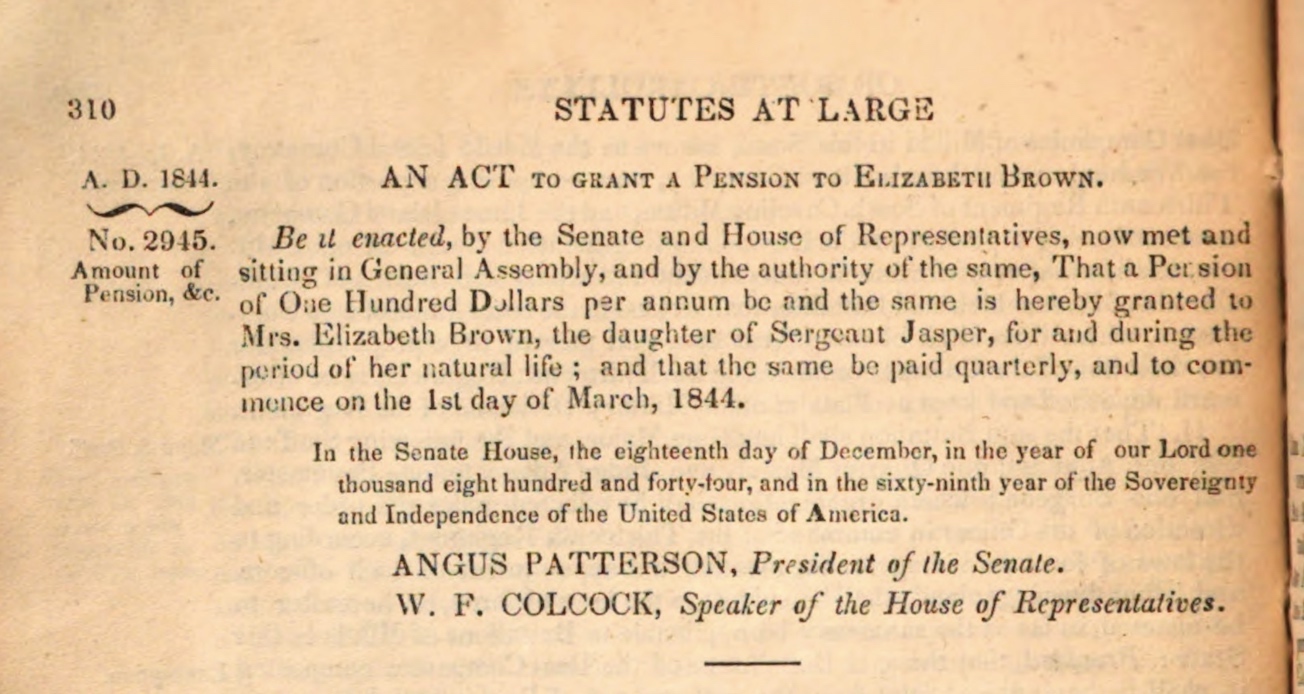

The effort to grant a state pension to Elizabeth Jasper Brown was approved by the South Carolina Senate and House of Representatives and passed into law on December 18th, 1844. On that day, governor William Aiken Jr. signed “An Act to grant a Pension to Elizabeth Brown,” the full text of which consists of just one compound sentence. The state government simply ordered “that a Pension of one hundred dollars per annum be and the same is hereby granted to Mrs. Elizabeth Brown, the daughter of Sergeant Jasper, for and during the period of her natural life; and that the same be paid quarterly, and to commence on the first day of March, 1844.”[20]

Starting in December 1844, Eliza Brown began receiving a series of quarterly payments of $25. At the same time, however, the Charleston Poor House continue to provide Mrs. Brown, now aged 74, with weekly rations of beef and bread. The government assistance was never intended to transform her life in a significant manner, but we can hope that it made the final months of her long life a bit more comfortable. Following the paper trails of both her state pension and her weekly food rations into the year 1845, I came to a dead end eleven months later.[21]

Starting in December 1844, Eliza Brown began receiving a series of quarterly payments of $25. At the same time, however, the Charleston Poor House continue to provide Mrs. Brown, now aged 74, with weekly rations of beef and bread. The government assistance was never intended to transform her life in a significant manner, but we can hope that it made the final months of her long life a bit more comfortable. Following the paper trails of both her state pension and her weekly food rations into the year 1845, I came to a dead end eleven months later.[21]

After the end of November 1845, the name Eliza Brown disappeared from the records of the Charleston Poor House. The State of South Carolina made an advance payment to her that month, perhaps because she was in desperate need, or perhaps to cover the expenses of her funeral.[22] Turning to the manuscript weekly ledgers of deaths and burials within the city of Charleston, now housed at CCPL, I found a record for a white female named Elizabeth Brown, estimated to be seventy years old (but probably closer to 75), who died sometime during the week of November 23–30, 1845, of “anasarca” (extreme generalized edema, caused by failure of the heart, liver, or kidneys). Like her brother, she was buried at “Bethel Burying Ground” near the southwest corner of Calhoun and Pitt Streets.[23]

Nearly seventy years after the tragic death of Sergeant William Jasper in 1779, the City of Charleston and the State of South Carolina contributed some small comforts to that brave soldier’s last descendant during her final years. For much of their lives, however, Jasper’s children lived in obscurity and want even while their father’s memory was celebrated and toasted across the state and beyond. If this fact seems incongruous and sad to you, then I would concur with the sentiment. Personal sacrifice and familial loss are the inevitable companions of warfare, but the United States learned over successive generations to place a greater value on the contributions of those who serve in defense of our nation. On Veterans Day, we acknowledge our collective debt to all those who have served in our military, and remember our commitment to rewarding their patriotism with a lifetime of praise and assistance.

[1] See the finding aid to the “Committee on Pensions and Revolutionary War Claims” on the website of the National Archives of the United States.

[2] See Southern Patriot, 1 August 1837; Charleston Courier, 4 November 1858.

[3] [Laurence K. Wells, ed.], “Compensation for Revolutionary Service,” South Carolina Magazine of Ancestral Research 1 (spring 1973): 60.

[4] [Wells], “Compensation for Revolutionary Service,” 60.

[5] St. John’s Lutheran Church [Charleston, S.C.], Register, 1755–1787, microfilm held at the South Carolina History Room at CCPL.

[6] [Wells], “Compensation for Revolutionary Service,” 61, 67.

[7] [Laurence K. Wells, ed.], “Compensation for Revolutionary Service,” South Carolina Magazine of Ancestral Research 1 (summer 1973): 156–60.

[8] See Act No. 1075, “An Act for Completing the Quota of Troops to be Raised by this State for the Continental Service; and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 28 March 1778, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 4 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1838), 410–13; Act No. 1250, “An Ordinance for securing to the Officers and Soldiers of the South Carolina Continental Line, and the Officers on the Staff, and the three Independent Companies commanded by Captain Bowie and Captain Moore, and to the Officers of the Navy of this State, the Lands promised to them by the Congress and the Legislature of this State,” ratified on 26 March 1784, in Cooper, ed., Statutes at Large, 4: 647.

[9] This grant is found at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Records of the Secretary of State, “Bounty Grants,” vol. 1: 6. A transcription can be found in “Bounty Grants to Revolutionary Soldiers,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 7 (July 1906): 173–78. A copy of the plat can be found at SCDAH, State Plat Books (Charleston Series), volume 26, page 100.

[10] For William Jasper’s travels, see his obituary in [Charleston] City Gazette, 4 August 1819; for his marriage on 3 March 1810 in Carteret County, see Ancestry.com. North Carolina, Marriage Index, 1741–2004 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2007), accessed on 7 November 2019.

[11] The Charleston directory of 1819 gives Jasper’s address as 351 King Street, and that of J. F. Plumeau as 350 King Street; see Schenck and Turner, The Directory and Stranger’s Guide for the City of Charleston . . . for the Year 1819 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1819), 55, 76. These address numbers reflect the city’s earliest street numbering system, in which the numbers commenced from the north end of the city (Boundary Street, now Calhoun) and proceeded southwardly. Odd and even numbers frequently appear on the same side of the street. This system was reversed in 1820–21, since which time the numbers have commenced on the south side of the city and proceeded northward, even numbers on the east and odd numbers on the west. A funeral announcement in City Gazette, 30 August 1819, confirms that Jasper’s residence, No. 351 King Street, was “near the corner of Broad Street.” John Francis Plumeau died in 1847, and the 1849 city directory places the widow Margaret Plumeau at No. 86 King Street, which was a brick tenement built and owned by the French Protestant Church that is now No. 98 King Street, between Broad and Tradd Streets. The present brick residences at 94, 96, and 98 King Street may post-date the death of William Jasper Jr., so it’s difficult to confirm the exact location of his residence in 1819. I am confident, however, that it was within this range of addresses, on land owned since colonial times by the French Protestant Church of Charleston.

[12] According to the “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston” for the week of 25 July to 1 August 1819 (held at CCPL), a white male named William Jasper, aged 42 years, died of “bilious fever” on Friday, 30 July, and was interred at “Methodist” burying ground. Jasper-themed columns in published in the Charleston Courier, issues of 4 and 18 November 1858, both confirm his burial at Bethel Methodist churchyard.

[13] [Charleston] City Gazette, 14 December 1824, page 4, “List of Letters Remaining in the Post-Office, Charleston, (S.C.) December 1, 1824,” includes “Brown, Wm. Jaspar [sic].” Joseph B. Kershaw, Fort Moultrie Centennial: Being an Illustrated Account of the Doings at Fort Moultrie, Sullivan’s Island, Charleston (S.C.) Harbor, Part II (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans, and Cogswell, 1876), 19, mentions the name of a second son, Thomas Brown, but Kershaw’s authority on this matter is dubious.

[14] Charleston Archive at CCPL, Records of the Commissioners of the Charleston Alms House (Poor House), minutes, 1834–1840, page 138. The residence of Eliza Brown is unclear, as there were at least two women named Elizabeth Brown in the published Charleston directories of the period 1819–45. The 1837 directory lists Eliza J. Brown as living on King Street (no address number), but she was a renter the precise location cannot be determined.

[15] See, among others, The Battle of Fort Moultrie (1826); Sergeants Jasper and Newton Rescuing American Prisoners from the British (no date) on the website of the U.S. Senate: https://www.senate.gov/art/paintings.htm.

[16] Southern Patriot, 1 August 1837: “[Communications.] Mr. White’s Picture—The Rescue—Jasper—and his Descendants.” While the anonymous author of this article appears ignorant of the state aid provided to Jasper’s family immediately after the Revolution, the full scope of the such assistance might never be known. Joseph B. Kershaw, Fort Moultrie Centennial: Being an Illustrated Account of the Doings at Fort Moultrie, Sullivan’s Island, Charleston (S.C.) Harbor, Part II (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans, and Cogswell, 1876), 19, states that Jasper’s daughter, whom he calls “Mrs. Elizabeth Martin Brown,” “received for about 20 years, from that Society, an annual pension of $150.” At present, however, there are no known surviving financial records of the local chapter of the Society of the Cincinnati to confirm or refute this assertion.

[17] United States Congress, House of Representatives, Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, Being the Second Session of the Twenty-Fifth Congress, Begun and Held at the City of Washington, December 4, 1837, and in the Sixty-Second Year of the Independence of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Allen, 1838), 525; Southern Patriot, 8 March 1838, “Washington, March 5.”

[18] United States Congress, Journal of the House of Representatives, 1837–38, 638, 707, 962.

[19] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina House of Representatives, 1844, pages 54, 84, 102, 143, 166, 225.

[20] State of South Carolina, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South-Carolina, Passed in December, 1844 (Columbia, S.C.: A. H. Pemberton, 1845), 310. On 12 August 2017, I personally checked the engrossed manuscript of this act at SCDAH to confirm that the pension was to commence on the first of March, 1844.

[21] Eliza’s age was given as 74 in a list of outdoor pensioners, dated 18 December 1844, in the Records of the Commissioners of the Charleston Alms House (Poor House), minutes, 1840–1846, page 268.

[22] SCDAH, South Carolina Treasury Records, Charleston District, Ledger D, October 1842–December 1850, page 12: The ledger shows “Eliza Brown” received five cash pension payments: a payment (No. 308) of $25 in December 1844; a payment (No. 315) of $25 in March 1845; a payment (No. 325) of $25 in June 1845; a payment (No. 329) of $75 in September 1845; and a payment (No. 339) of $25 in November 1845. The first four payments, totaling $150, occurred quarterly, and cover a period of one and a half years. The fifth and final payment was made prior to the end of the quarter, however, perhaps indicating Mrs. Brown was in poor health and needed the extra money.

[23] Charleston Archive at CCPL, “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston,” November 23–30 1845. I believe the age of 70 years given in this record is a rough estimate, and that the age of 74 recorded in the Poor House minutes in December 1844 (cited above), is a more accurate figure. Thus Eliza was probably around 75 years old at the time of her death in November 1845.

PREVIOUS: Mackey’s Morphine Madness: The 1869 Shootout at Charleston City Hall, Part 2

NEXT: The Historical Landscape of the New Baxter-Patrick James Island Library

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments