Charleston’s Second Ice Age: Rise of the Machines

Processing Request

Processing Request

Ice was a summer luxury in antebellum Charleston, brought southward in blocks by ships from New England. The invention of ice-making machines after the Civil War transformed the industry, but a sour economy and consumer skepticism delayed local adoption of the new technology. Cheaper “artificial ice” finally debuted in the Palmetto City in 1888, while deliveries of imported “natural ice” slowly declined. The rise of mechanized ice production at the turn of the twentieth century transformed food and beverage habits across the Lowcountry, and established an appetite for a cooler, modern lifestyle.

Charleston’s First “Ice Age,” which I described in Episode No. 49, commenced in 1798, when ships from New England began bringing frozen water to the Port of Charleston. The first wave of ice imports lasted for nearly a decade, followed by the disruptive War of 1812 and then a national post-war boom. Massachusetts ice-tycoon Frederic Tudor established a new ice house in Charleston in the spring of 1817, after which Charlestonians enjoyed regular access to Northern ice to cool hot Southern summers. Ice wasn’t just for urbanites, however; Charleston was the nexus of frozen-water deliveries to communities and households across the Lowcountry of antebellum South Carolina. The blocks were unloaded on the city wharves and hauled to specially-designed “ice houses” within the Palmetto City. A portion of the imported natural ice was taken by boat to other coastal communities, and a portion was loaded onto wagons and transported inland.

In antebellum Charleston, as elsewhere during the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, most of this natural ice was consumed by a new breed of food wholesalers who used it to extend the viability of fresh meat, seafood, fruit, and vegetables. These chilled foodstuffs could be shipped to distant communities or sold to the proprietors of new-fangled restaurants. The owners of early commercial icehouses also rented space within refrigerated storage rooms to butchers and restauranteurs for storing cuts of meat and fish that didn’t sell right away. Barrooms and saloons could also sell summer novelties like iced drinks and ice cream to overheated customers. Last, but not least, on the ice food-chain, retail customers could purchase small quantities of ice for home use. Imported natural ice was a relatively scarce commodity in antebellum South Carolina, however, so the domestic use of ice was a luxury limited to a small portion of the population.

Prior to the Civil War, there were just two ice-importing firms in Charleston. The first was owned by the Tudor Ice Company of Massachusetts, which opened the first commercial ice house on Fitzsimons’s Wharf in 1817, and then in 1827 moved to a site now identified as 182 Meeting Street. A group of local businessmen formed a new ice company in 1840 and the following year opened the “Charleston Ice House” at the northeast corner of Church and North Market Streets. Alva Gage (1820–1896), a native of New Hampshire, purchased the latter establishment in 1856 and quickly emerged as the dominant force in the city’s ice business.

Prior to the Civil War, there were just two ice-importing firms in Charleston. The first was owned by the Tudor Ice Company of Massachusetts, which opened the first commercial ice house on Fitzsimons’s Wharf in 1817, and then in 1827 moved to a site now identified as 182 Meeting Street. A group of local businessmen formed a new ice company in 1840 and the following year opened the “Charleston Ice House” at the northeast corner of Church and North Market Streets. Alva Gage (1820–1896), a native of New Hampshire, purchased the latter establishment in 1856 and quickly emerged as the dominant force in the city’s ice business.

South Carolina’s secession from the United States in December 1860 did not immediately end the flow of Northern ice into Charleston, but the shipments ceased after the commencement of the Civil War in April 1861. The Tudor Ice Company resumed shipments to the Palmetto City in May 1865, immediately after the conclusion of the war, and Alva Gage likewise reopened the Charleston Ice House on North Market Street. For the next twenty-odd years, the ice trade continued much as it had during the antebellum years.[1]

Meanwhile, in Europe and in the United States, a number of engineers were tinkering with various methods of producing ice through artificial means. There were several prominent figures in this scientific pursuit, some of whom are better remembered that others. The American physician John Gorrie (1803–1855), for example, is widely credited as the inventor of artificial refrigeration. Doctor Gorrie, by the way, might or might not have been born and raised in Charleston. None of the vast amount of biographical literature devoted to the man provides any definite information about his early life, however. Although his personal background is something of an enigma, I might be on the trail of solving that mystery. Stay tuned for a future program about the curiously elusive Gorrie family.

John Gorrie’s early work in creating artificial refrigeration, which he patented in 1850, was refined and perfected by a subsequent generation of scientists like Ferdinand Carré and Charles Tellier. Although their work used slightly different methods, each shared a common root. The process of freezing water in a warm atmosphere is based on a physical reaction between naturally-occurring elements. In short, it’s a thermodynamic heat exchange. Artificial ice is not the result of a chemical or synthetic process, and it does not create any harmful by-products. The mechanical production of artificial ice combines two distinct branches of science: the laboratory study of natural elements and their physical properties, and the engineering of reliable and fairly compact steam-powered motors. At the risk of over-simplifying the process, I’ll offer this brief description of artificial ice production, based on the technology of the late nineteenth century:

Cans or buckets of fresh, filtered water are suspended in a bath of briny water. A steam-powered pump forces liquid ammonia from a high-pressure reservoir into a closed network of coiled pipes immersed in the same bath of briny water. As the liquid ammonia expands in the pipes, it changes into a gaseous state and draws heat energy from the adjacent brine. The brine chills rapidly and, in turn, draws heat energy from the fresh water within the cans. While the salt in the brine prevents it from freezing, the fresh water in the cans freezes into a solid block over a number of hours. The ice is then removed from the cans, which are refilled with fresh water. Meanwhile, the gaseous ammonia is pumped back to the reservoir, re-pressurized into a liquid state, and re-circulated through the system to repeat the chilling process. By automating the work of filling and emptying the cans, this production cycle can continue around the clock with minimal human effort.

The people of Charleston, like other Americans of the late 1860s, read about the science of artificial ice in newspapers and magazines of the era. While communities to the north and west were scrambling to harness the latest cooling technology, the people of South Carolina were largely struggling to survive. The Civil War devastated the economy of the Southern states and destroyed the traditional systems of labor and agriculture. Merchants and investors in Charleston sought to keep up with their Northern neighbors, but there was little capital available for new ventures.

Local readers took notice, however, when the Charleston Daily News reported in July 1870 that a factory in Connecticut was building a Tellier ice-making machine for a business in Charleston.[2] By January of 1871, a group of men organized a new concern called the Charleston Ice Manufacturing and Refrigeration Company. Inspired by these developments, the Daily News made the following bold prediction: “It is probably a mere question of time whether some invention of this character will not be generally employed in all Southern communities—nay, whether our very houses will not be cooled to an extent that will assuage fevered brows, relieve pendant shirt collars, and sorely distress mosquitoes. Evidently the world moves, and we are about to have the benefit of some of its progress.”[3]

Local readers took notice, however, when the Charleston Daily News reported in July 1870 that a factory in Connecticut was building a Tellier ice-making machine for a business in Charleston.[2] By January of 1871, a group of men organized a new concern called the Charleston Ice Manufacturing and Refrigeration Company. Inspired by these developments, the Daily News made the following bold prediction: “It is probably a mere question of time whether some invention of this character will not be generally employed in all Southern communities—nay, whether our very houses will not be cooled to an extent that will assuage fevered brows, relieve pendant shirt collars, and sorely distress mosquitoes. Evidently the world moves, and we are about to have the benefit of some of its progress.”[3]

Despite such glowing journalistic predictions, the early reports of the Charleston Ice Manufacturing and Refrigeration Company proved premature. The firm never opened for business, and I can find no record of it producing a single ice cube. While the inhabitants of other Southern cities like New Orleans, Savannah, and Columbia witnessed the dawning of an era of artificial coolness during the 1870s, the people of Charleston were left in the heat. Shipments of natural ice continued to flow into the Palmetto City for the remainder of the nineteenth century, but artificial competition was just around the corner.

Charleston’s second ice age formally commenced in the autumn of 1887, when Alva Gage and a number of local capitalists organized (or perhaps re-organized) the Charleston Ice Manufacturing Company.[4] The firm built a modestly-sized steam-powered ice plant on the east side of Gage’s existing building at the northeast corner of Church and Market Streets, drilled several Artesian wells to obtain fresh water, and started production in the spring of 1888. The new factory produced up to twenty-four tons of artificial ice per day in large blocks weighing approximately three hundred pounds each. The business was an immediate success, and the Charleston News and Courier deemed artificial ice a “most necessary luxury of summer.” By the autumn of 1889, the new ice firm was raising capital for a significant expansion. They dismantled the old Charleston Ice House and built a larger plant that began producing seventy-five tons of ice per day in the spring of 1890.[5]

The advent of artificial ice in Charleston had a profound and lasting effect on the local economy and culture during the twilight of the nineteenth century. Although a handful of entrepreneurs continued to import and sell natural ice for several more years, the availability of seemingly limitless quantities of ice year-round inspired new ways of thinking about food and beverages. The formerly-novel idea of chilling meat, fish, and perishable items to extend their usefulness became an accepted fact of the food and beverage industry, which blossomed exponentially thanks to artificial refrigeration. Iced tea and chilled mint juleps, once reserved for the wealthiest citizens, became standard drinks in many homes and barrooms. The business of truck farming and shipping local farm products to distant cities was improved by the development of chilled railroad cars and ice wells in steamboats plying between Charleston and other ports. Ice became a major industry throughout the South and across the United States before the existence of the automobile and the airplane.

The people of Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry took a bit longer to warm to artificial ice, however. “Ice here is no longer classed among the luxuries,” said the News and Courier in the summer of 1891, “it is a necessity.” Nevertheless, continued the newspaper, “Charlestonians have been slow to become generally accustomed to the use of ice.” Despite the relatively inexpensive nature of the article, “there are comparatively few families who use ice during the entire year.” The local consumption during the summer of 1891 was reported to be approximately sixty tons of ice per day, while it dropped to around fifteen tons a day during the cooler months. The “antiquated idea that [ice] is still a luxury” was compounded by a lingering preference for natural ice from New England. Some customers believed that natural ice melted at a slower rate than artificial ice and claimed to discern an odd smell and taste in the manufactured article.[6]

The growing domestic use of ice—both natural and artificial—during the last quarter of the nineteenth century was augmented by an innovative delivery system. Prior to 1873, customers who wanted a relatively small amount of ice for home use were obliged to walk or ride to one of the local ice depots and carry home their melting purchase. An upstart business called the Palmetto Ice Company started delivering blocks of natural ice to residential customers in the spring of 1873, using a small fleet of wagons pulled by mules and horses. When that company folded one year later and Alva Gage purchased all of its assets, Charlestonians clamored for the return of the convenient delivery carts. Mr. Gage, in his pre-artificial-ice days, grudgingly complied, and thereby cemented a customer service model that continued into the middle of the twentieth century.[7] To paraphrase a popular business mantra: if you deliver it, they will pay!

The growing domestic use of ice—both natural and artificial—during the last quarter of the nineteenth century was augmented by an innovative delivery system. Prior to 1873, customers who wanted a relatively small amount of ice for home use were obliged to walk or ride to one of the local ice depots and carry home their melting purchase. An upstart business called the Palmetto Ice Company started delivering blocks of natural ice to residential customers in the spring of 1873, using a small fleet of wagons pulled by mules and horses. When that company folded one year later and Alva Gage purchased all of its assets, Charlestonians clamored for the return of the convenient delivery carts. Mr. Gage, in his pre-artificial-ice days, grudgingly complied, and thereby cemented a customer service model that continued into the middle of the twentieth century.[7] To paraphrase a popular business mantra: if you deliver it, they will pay!

Another popular innovation was the commercial production of refrigerators, or “iceboxes,” as they were more commonly called. Insulated wooden boxes with compartments to store ice had been available since the early nineteenth century, but these domestic refrigerators became increasingly common and affordable around the turn of the twentieth century. A Charleston ice executive estimated in 1915 that local households each consumed an average of twenty-five pounds of ice per day, which was sufficient to chill an icebox full of perishable groceries.[8] Iceboxes became fixtures of American kitchens as the years went by, long before electric refrigerators came into common use.

The manufacture and distribution of ice was also big business that spurred the rise and fall of large corporate entities—locally, regionally, and nationally. The Charleston Ice Manufacturing Company, for example, was a subsidiary of a larger entity called the Central Ice Company, and was affiliated with a trade-protection group called the Southern Ice Exchange.[9] The success of the Charleston Ice Manufacturing Company in the 1890s quickly overwhelmed the smaller local companies that continued to import natural ice, and soon held an ice monopoly in the city. To spur a reduction in retail and wholesale prices, the Consumers’ Ice Company arrived in 1899 offering cheap natural ice imported from Maine. One year later, however, the Consumers’ company purchased land on the north side of Wolfe Street (now misspelled Woolfe) and built its own factory to produce thirty-five tons of artificial ice per day. That plant went into operation in the spring of 1901 and was expanded several times over the subsequent decade.[10] So too was the Mutual Ice Manufacturing and Cold Storage Company, which commenced production of seventy-five tons a day at the east end of Inspection Street in 1899.[11] The Germania Brewing Company, which occupied both sides of Hayne Street between Church and Anson Streets, produced many tons of ice as an extension of its refrigerated beer production.[12] The Citizens’ Ice Company erected in 1900 a small facility at the northeast corner of Tradd and Chisolm Streets.[13] Local fishmonger Thomas W. Carroll built his own ice plant on East Bay Street in 1906, producing initially around twenty tons a day for the export of local seafood.[14]

By the summer of 1907, the total production of artificial ice in Charleston exceeded 250 tons per day. Wholesale and retail customers within the city purchased only about half that amount, however, according to a statement from local industry leader Samuel Lapham (1850–1929). In fact, said Lapham, the oldest ice plant at the corner of Market and Church Street was idle that summer. A significant cause for this decline, he said, was the proliferation of new electric-powered ice machines. Small towns and communities across the Lowcountry and beyond were rapidly building their own ice factories and no longer depended on plants in urban Charleston for supply.[15] A memorable example of that trend was T. W. Carroll’s 1909 construction of a large new factory at a railroad nexus called Ashley Junction or Seven-Mile Crossing, now the southeast end of Durant Avenue in North Charleston.[16]

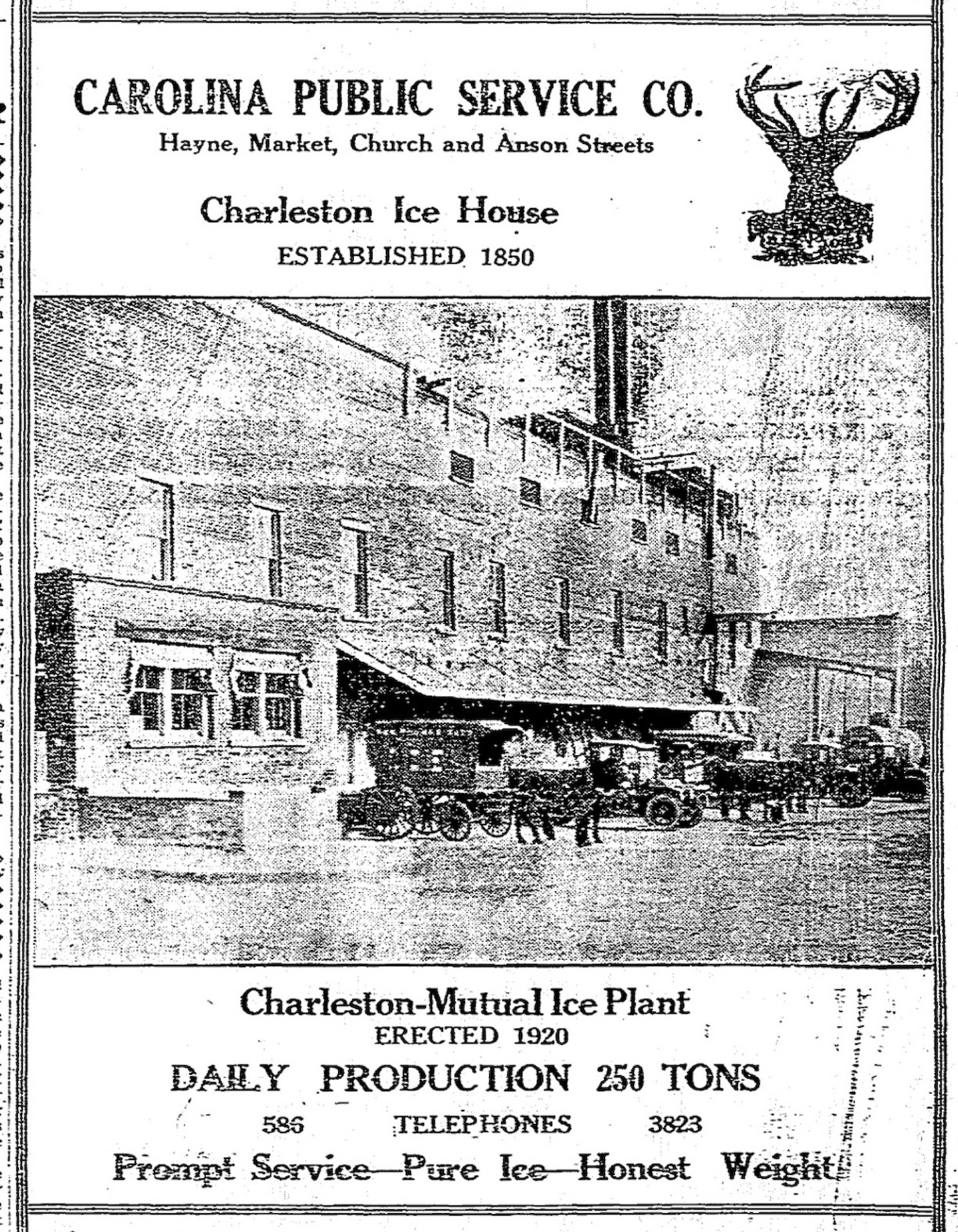

Despite the relatively slack business trend noted by Samuel Lapham in 1907, the manufacture and consumption of ice continued to increase in subsequent months and years. A new corporate entity called the Carolina Public Service Company, chartered in 1912, purchased ice plants across South Carolina and soon controlled most of the ice-production facilities in the Charleston area. While the Citizens’ Ice Company melted in 1913, the Consumers’ and Carroll plants expanded in 1914, and the Germania Brewery spawned its own Crystal Ice Company in 1915.[17] That same year, a South Carolina referendum led to the prohibition of alcohol beverages, and the local brewing industry collapsed. The Carolina Public Service Company purchased the Germania property adjacent to its plant at the corner of Market and Church Streets in 1916. The following year, the company demolished a hodge-podge of old buildings and commenced erecting a monolithic, state-of-the art ice factory that covered the entire block bounded by Market, Church, Hayne, and Anson Streets. The adjacent block, bounded by Church, Pinckney, Anson, and Hayne Streets, was occupied by the ice company’s storage and garage facilities. Shortages of labor and materials during the final stages of World War I delayed completion of the massive plant, but it emerged in 1920 with a total output of 240 tons of ice per day.[18] The appearance of a smaller entity, the Arctic Ice and Coal Company, at the east end of Columbus Street in 1917 further expanded the local market.[19]

Despite the relatively slack business trend noted by Samuel Lapham in 1907, the manufacture and consumption of ice continued to increase in subsequent months and years. A new corporate entity called the Carolina Public Service Company, chartered in 1912, purchased ice plants across South Carolina and soon controlled most of the ice-production facilities in the Charleston area. While the Citizens’ Ice Company melted in 1913, the Consumers’ and Carroll plants expanded in 1914, and the Germania Brewery spawned its own Crystal Ice Company in 1915.[17] That same year, a South Carolina referendum led to the prohibition of alcohol beverages, and the local brewing industry collapsed. The Carolina Public Service Company purchased the Germania property adjacent to its plant at the corner of Market and Church Streets in 1916. The following year, the company demolished a hodge-podge of old buildings and commenced erecting a monolithic, state-of-the art ice factory that covered the entire block bounded by Market, Church, Hayne, and Anson Streets. The adjacent block, bounded by Church, Pinckney, Anson, and Hayne Streets, was occupied by the ice company’s storage and garage facilities. Shortages of labor and materials during the final stages of World War I delayed completion of the massive plant, but it emerged in 1920 with a total output of 240 tons of ice per day.[18] The appearance of a smaller entity, the Arctic Ice and Coal Company, at the east end of Columbus Street in 1917 further expanded the local market.[19]

At the beginning of the 1920s, and concurrent with the advent of a national prohibition of alcoholic beverages, the total ice production within urban Charleston exceeded 600 tons per day. Despite this large output, local consumers complained of ice shortages in the summers of 1918 and 1920, while local producers pushed their machines to maximum capacity.[20] The last major development in the Charleston ice market was the organization of a new corporate entity in December 1924 called the Southern Ice Company, which immediately purchased nearly all of the local ice facilities and rebranded the delivery wagons.[21] This moment represented the peak of manufactured ice in the Charleston area, after which a discernable evolution commenced.

The most visible change in the local ice business was the mechanization of delivery. During the late 1910s, a handful of gasoline-powered trucks began delivering blocks of ice to residential customers within the city. The fleet of ice trucks increased steadily throughout the 1920s and 1930s, augmented briefly by several small electric vehicles better suited to Charleston’s narrow streets. Conversely, a diminishing stable of horses and mules continued to pull ice wagons at a moderate trot to a shrinking radius of downtown customers through the 1940s. The last ice delivery mules were sold in October 1951, while the ice trucks reached farther into the suburbs to serve customers.[22]

The domestic use of ice in general declined rapidly between the 1920s and the 1950s, for a variety of reasons. The same technology used to manufacture blocks of ice was adapted to create refrigerated air, which could be used to cool confined spaces such as domestic refrigerators, delivery trucks, railroad cars, and ships. Ice was heavy, cumbersome, and perishable. In 1918, a local ice executive acknowledged that one-quarter of all manufactured ice melted before it was used—a waste that ultimately proved both inconvenient and unsustainable.[23] Refrigerated air, not frozen water, was the wave of the future during the second quarter of the twentieth century.

The domestic use of ice in general declined rapidly between the 1920s and the 1950s, for a variety of reasons. The same technology used to manufacture blocks of ice was adapted to create refrigerated air, which could be used to cool confined spaces such as domestic refrigerators, delivery trucks, railroad cars, and ships. Ice was heavy, cumbersome, and perishable. In 1918, a local ice executive acknowledged that one-quarter of all manufactured ice melted before it was used—a waste that ultimately proved both inconvenient and unsustainable.[23] Refrigerated air, not frozen water, was the wave of the future during the second quarter of the twentieth century.

The home delivery of ice blocks declined sharply after World War II as a booming post-war economy spurred a new spirit of consumerism. Electric refrigerators, which had existed for decades, quickly replaced the remaining iceboxes in households across America. The massive Southern Ice manufacturing facility on North Market Street was shuttered in the early 1950s and demolished in 1960, while the company pivoted to the sale of electric appliances and heating oil.[24] The business of manufacturing ice never disappeared, but it shrank and evolved with the times. Seafood wholesalers, for example, continue to use crushed ice to ship their products around the world, and packaged ice cubes are still available at supermarkets and convenience stores everywhere.

Let’s conclude this sprawling historical journey with a quick review and preview. Charleston’s second ice age commenced with the arrival of ice-making machines in 1888 that triggered an explosion of refrigerated commerce and domestic habits that continued to the middle of the twentieth century. Frozen water imported from New England, the catalyst of Charleston’s first ice age in 1798, disappeared from local markets in 1901, and manufactured ice became an increasingly-local commodity in the early years of the new century. The proliferation of artificial refrigeration fueled a growing appetite for the chilled beverages and chilled food preservation that we now take for granted.

The technology behind the creation of ice in a warm atmosphere, pioneered in the mid-nineteenth century, also spawned new concepts of personal comfort and health in the second quarter of the twentieth century. Artificially-chilled air, a refreshing luxury that debuted after the jazzy era of Prohibition, rendered Charleston’s sultry summers more bearable, which in turn encouraged more tourists to drop by for a visit or settle here permanently. In a future program, perhaps next summer, we’ll crank up the air conditioning and explore the chilling details of Charleston’s third ice age.

[1] Both ice companies recommenced advertising in late May 1865, and by 25 May received permission from the military commandant to open for limited business on Sunday mornings; see Charleston Courier, 25 May 1865, page 3, “Ice Notice.”

[2] Charleston Daily News, 18 July 1870, page 3, “Making Ice.”

[3] Daily News, 3 January 1871, page 3, “The Ice Question”; Daily News, 30 January 1871, page 1, “From Columbia.”

[4] The firm’s notice of incorporation appears in Charleston News and Courier, 30 November 1887, page 7; further business details appear in News and Courier, 7 December 1887, page 8, “Making Our Own Ice”; News and Courier, 1 January 1890, page 3, “Copartnership Notice.”

[5] News and Courier, 21 May 1888, page 1, “The Ice Trust”; News and Courier, 31 March 1889, page 2, “The Price of Ice”; News and Courier, 2 October 1889, page 16: “Frozen Comfort”; News and Courier, 2 March 1890, page 8, “No Ice Famine Here”; News and Courier, 7 May 1890, page 5, “Charleston Ice Manufacturing Company.”

[6] News and Courier, 20 June 1891, page 2, “Some Seasonable Reflections; Evening Post, 11 August 1899, page 8, “Cheap Ice.”

[7] News and Courier, 14 May 1874, page 1, “Ice—Good News for Housekeepers; News and Courier, 15 May 1874, page 1, “The Ice Question. The Delivery by Carts.”

[8] Evening Post, 5 March 1915, page 14, “The Ice War Is Still A-Raging.”

[9] Local references to the Central Ice Company and the Southern Ice Exchange can be found in numerous newspaper articles in the late 1890s and the early 1900s. See, for example, News and Courier, 4 December 1889, page 7, “A New Artesian Well”; Evening Post, 23 February 1897, page 5, “Business and Pleasure Combined”; Evening Post, 11 June 1898, page 79, “Charleston Ice Mfg. Co.”

[10] For early references to the Consumers’ Ice Company, see Evening Post, 11 August 1899, page 8, “Cheap Ice”; Evening Post, 15 September 1899, page 5, “The Ice War Waging Along”; Evening Post, 9 March 1901, page 2, “Another Ice Factory”; Evening Post, 25 June 1903, page 2, “How Ice Is Made”; Evening Post, 21 August 1913, page 8, “To Enlarge Ice Plant”; Evening Post, 18 July 1914, page 9, “Ice Plant Has Been Quintupled.”

[11] Evening Post, 25 October 1897, page 5, “The New Ice Plant”; News and Courier, 22 May 1898, page 8: “Went to Work Yesterday”; Evening Post, 1 July 1898, page 5, “It Cuts No Ice”; News and Courier, 3 April 1911, page 26, “The Ice Delivery Co.”; News and Courier, 14 August 1918, page 8, “Public Is Urged To Buy Less Ice.”

[12] Evening Post, 22 November 1898, page 5, “Enlarging its Plant”; News and Courier, 14 December 1901, page 6, “Ice! Ice! Ice!”; Evening Post, 11 May 1916, page 9, “Manufacturing Ice Only.”

[13] News and Courier, 1 August 1900, page 4, “Citizens’ Ice Company.”

[14] News and Courier, 12 July 1906, page 10, “Cold Storage Plant.”

[15] Evening Post, 5 August 1907, page 5, “Ice Is Cheap Here Declares Official.”

[16] Evening Post, 29 October 1909, page 7, “New Ice Plant In the Suburbs”; Evening Post, 17 November 1909, page 10, “Site For New Ice”; News and Courier, 18 January 1914, page 11, “Bigger Ice Plant at the Junction.”

[17] Evening Post, 9 April 1913, page 10, “Legal Notice”; Evening Post, 18 July 1914, page 9, “Ice Plant Has Been Quintupled”; News and Courier, 18 January 1914, page 11, “Bigger Ice Plant at the Junction”; Evening Post, 1 March 1915, page 7, “New Ice Factory.”

[18] Evening Post, 19 December 1916, page 4, “Big Ice Factory On Brewery Site”; Evening Post, 22 January 1917, page 50, “Carolina Public Service Company”; Evening Post, 3 July 1917, page 8, “Plant Nears Completion”; News and Courier, 15 August 1918, page 8, “Says Ice Famine Is Just About Over”; News and Courier, 29 June 1920, page 12, “Local Capitalists Control Ice Plant”; Evening Post, 27 April 1920, advertisement on page 9 of “Elks Booster Edition”: “Carolina Public Service Co.”; News and Courier, 20 May 1923, page C-14, “Entire Square For Ice Plant.” The resulting factory is depicted on page 57 of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map of Charleston, 1944 edition.

[19] News and Courier, 16 March 1917, page 7, proceedings of City Council meeting of 13 March; News and Courier, 3 June 1917, page 12, “New Ice Plant to Open”; News and Courier, 5 July 1917, page 2, “Doing A Nice Business.”

[20] News and Courier, 10 August 1918, page 6, “Brisk Demand For Ice Due to the Shortage”; News and Courier, 14 August 1918, page 8, “Public Is Urged To Buy Less Ice”; News and Courier, 15 August 1918, page 8, “Says Ice Famine Is Just About Over; Evening Post, 8 July 1920, page 10, “The Heavy Demand Makes Ice Short.”

[21] Evening Post, 5 December 1924, page 3, “Half-Million Transaction?”; News and Courier, 16 December 1924, page 16, “Stone & Webster Take Over Plant”; Evening Post, 5 January 1925, page 8, “Another Ice Company Deal”; Evening Post, 22 January 1925, page 9, “Charters Granted.”

[22] Evening Post, 23 November 1951, page 1-C, “Era Ends As Ice Co. Retires Mules.” The last two delivery mules and wagons was advertised for sale in the classified section of the News and Courier, 16–22 October 1951.

[23] News and Courier, 15 August 1918, page 8, “Says Ice Famine Is Just About Over.”

[24] A largely-inaccurate historical review of the local ice trade appears in Evening Post, 5 August 1960, page 1-B, “Old Ice Plant on Market Street Is Being Razed.” The City of Charleston permitted the closure of Hayne Street between Church and Anson Streets in 1973, with an option to re-open the block by 1 January 2023. See News and Courier, 4 January 1973, page 22, “School Requests Street Closing”; Evening Post, 6 September 1973, page 9-B, Proceedings of City Council Meeting of 21 August 1973. The Anson restaurant at the southeast corner of Anson and Guignard Street was built after World War II as an appliance showroom for the Southern Ice Company.

NEXT: Careening across the Lowcountry in the Age of Sail

PREVIOUSLY: Clementia Mineral Spring: Ghost Town that Never Was

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments